Menu (linked Index)

Electrical Power Equations

Last Update: January 13, 2026

- Introduction

- Power Equation From Ohm’s Law

- Direct Current Power Equations

- Single Phase AC Power Derivation

- Three Phase AC Power Derivation

- Summary of Power Equations

- Single Phase AC Power Triangle

- Three Phase AC Power Triangle

- Get Clear on Electric Power Units of Measure

- Analogies: Beer vs Physics

- Power Equations in Unbalanced Three Phase Systems

Introduction

This series provides a technical breakdown of electrical power, moving from fundamental DC theory to complex three-phase systems.

We begin with the derivation of power equations from Ohm’s Law and progress through the mathematical origins of single-phase and balanced three-phase AC power.

After establishing these algebraic foundations, the focus shifts to the geometric and physical reality of the power triangle.

We distinguish between active, reactive, and apparent power—using both the traditional “Beer Analogy” and the more physically accurate “Horse and Railcar” model.

And we conclude with the methodology required to calculate power in unbalanced systems where standard symmetry fails.

I utilize results from two of my posts that I have listed below, so be sure to review them if you need to.

Power Equation From Ohm’s Law

Recall Ohm’s law which states that the current through a conductor between two points is

- directly proportional to the voltage across the two points, and

- inversely proportional to the resistance between them.

1. V = IR (Ohm’s Law)

where

- V = voltage where 1 V = 1 m2kgs-3A-1 = 1 Watt/A = 1 W/A = 1 Joule/C = 1 J/C

- R = resistance where 1 Ω = 1 m2kgs-3A-2 = 1 V/A

- I = current where 1 Amp = 1 A = 1 Coulombs/second = 1 C/s

Ohm (Georg) came up with this in 1827.

Fast forward about 13 years to 1840/1 and we have James Prescott Joule developing another relationship.

Joule’s Law, determined empirically, states that:

the heat (energy) generated (H) in a conductor is directly proportional to

- the square of the current (I) flowing through it,

- the electrical resistance (R) of the conductor, and

the time (t) for which the current flows

where

- H = heat energy in Joules (J) where 1 J = 1 Nm = 1 m2kgs-2

2(a). Heat = I2(R)(time) = Joule’s Law

Divide t into both sides and recognize that H/t = energy/t= Power Dissipated (turned into heat) = Pheat. So,

2(b). H/t = Power Dissipated = Pheat = I2R (Joule’s Law in Power form)

where

- Pheat = Power Dissipated (turned into heat) in a resistive component where 1 watt = 1 W = 1 m2kgs-3 = 1 J/s

- It is frequently associated with power loss because that dissipated power is often in the form of unwanted heat

Substitute for I in equation 2. using Ohm’s law in equation 1. So equation 2 becomes:

3. P = (V2/R2)R = V2/R; Power Law using V and R

Substitute for R in equation 2. using Ohm’s law, equation 1. So equation 2 becomes:

4. P = (I2)(V/I) = IV; Basic Power Law (using I and V)

Direct Current Power Equations

In a DC circuit, voltage and current are constant.

So we can use the three formulas we derived above.

4. P = (I2)(V/I) = IV; Basic Power Law (using I and V)

- This equation defines the rate at which energy is supplied or consumed by any two-terminal component (source or load) in the circuit.

- It represents the total electrical power associated with that component.

2(b). P = Pheat = I2R = Resistive Loss = Power Dissipated

- This form is often used to calculate power dissipated as heat (Joule Heating) in resistors or wires.

3. P = (V2/R2)R = V2/R; Power Law using V and R

- This form is often used for components operating across a constant voltage source (e.g., parallel circuits).

Single-Phase AC Power Derivation

The goal is to find the Real Power (P), which is the average value of the instantaneous power over one cycle.

Step A: Define the Time-Varying Waveforms

Represent instantaneous voltage v(t) and current i(t) as cosine functions.

Assume a phase shift Φ between them (the angle by which current lags or leads voltage).

5. v(t) = Vmcos(ωt)

6. i(t) = Imcos(ωt – Φ)

- t = time

- Vm, Im : Peak (maximum) values (amplitudes of sinusoids)

- ω = 2πf : Angular frequency.

- f = frequency

Step B: Find Instantaneous Power p(t)

By definition

7. instantaneous power = p(t) = v(t) x i(t)

Substitute for v(t) and i(t):

8. p(t) = Vmcos(ωt) x Imcos(ωt – Φ)

9. p(t) =VmImcos(ωt)cos(ωt – Φ)

Apply the trigonometric identity:

10. cos(A)cos(B) = 1/2[cos(A-B) + cos(A+B)]

- Let A = ωt and B = ωt – Φ

- A-B = Φ

- A+B = 2ωt – Φ

Substitute these into the identity (equation 10):

11. p(t) = Vm Im/2 [cos(Φ) + cos(2ω t – Φ)]; Single phase AC circuit instantaneous power

Step C: Integrate to find Average (Real) Power (P)

Real power is the average of p(t) over one period T

In calculus, there is a standard formula for the Average Value of any continuous function f(x) over an interval from a to b:

12. favg = 1/(b-a)∫a-b f(x) dx

- Remember that an integral “∫” is the mathematical process of calculating the exact total accumulation of a quantity by summing up an infinite number of infinitesimally small parts.

- Read my article Integration Definition and Rules for a refresher on integration

- In our case, the interval is one full period, starting at 0 and ending at T.

- The “length” of that interval (b – a) is T – 0 = T.

- Therefore, the fraction out front is 1/T.

So,

13. P = Real Power = 1/T∫0->T p(t)dt

Substitute in the expression for p(t) (equation 11):

14. P= 1/T∫0->T [Vm Im/2 [cos(Φ) + cos(2ω t – Φ)]] dt

Breaking the integral into two parts:

- The Constant Term: ∫0->T cos(Φ)dt = Tcos(Φ)

- The Oscillating Term: ∫0->T cos(2ωt – Φ)dt = 0

- (The average of a pure sine/cosine wave over its period is always zero).

So equation 14. becomes:

15. P = (VmIm)/(2)cos(Φ); Single-phase AC circuit Average Power (or Real Power)

Step D: Convert to RMS Values

Root mean squared versions of V and I are defined as: (see my article RMS (Root Mean Square) of a Sinusoid )

16. Vrms = Vm/√2

17. Irms = Im/√2

We can rewrite the denominator 2 in equation 15 as as √2 x √2

18. P = (Vm/√2)(Im/√2)cos(Φ)

Now, substitute in equations 16. and 17.

19. P = Vrms Irmscos(Φ); Single-phase AC circuit Standard Average Power Equation

Three-Phase AC Power Derivation

In a balanced three-phase system, the total power is the sum of the power in each of the three phases.

Step A: Define the Three Phases

Each phase is shifted by 120 degrees (2π/3 radians):

20. p1(t) = Vph Iph [cos(Φ) + cos(2ωt – Φ)]

21. p2(t) = Vph Iph [cos(Φ) + cos(2ωt – 120o – Φ)]

22. p3(t) = Vph Iph [cos(Φ) + cos(2ωt – 240o – Φ)]

and remember that Vph and Iph are RMS values.

Step B: Sum the Total Instantaneous Power

23. ptot= p1(t)+ p2(t) + p3(t)

Factor out Vph and Iph:

24. ptot = Vph Iph [cos(Φ) + cos(2ωt – Φ) + cos(Φ) + cos(2ωt – 120o – Φ) + cos(Φ) + cos(2ωt – 240o – Φ)]

25. ptot = Vph Iph [3cos(Φ) + cos(2ωt – Φ) + cos(2ωt – Φ – 120o ) + cos(2ωt – Φ – 240o )]

Mathematically, the sum of three sinusoids of the same frequency shifted by 120 degrees is zero.

Thus, the oscillating terms cancel out entirely and we get

26. ptot = 3Vph Iphcos(Φ); Total Active Power (using Phase values) for a balanced three-phase system (applies to both wye or delta circuits).

where Vph and Iph are RMS values.

Step C: Convert to Line Values (VL , IL)

In practical systems, we usually measure Line-to-Line Voltage (VL) and Line Current (IL).

The relationship depends on the connection (Wye or Delta).

See my article Wye and Delta Three Phase Circuits to brush up on the properties of these circuits

For a Wye (Y) Connection:

27. VL = √3 Vph

28. Vph = VL/√3

29. IL = Iph

Substitute these into equation 26 (ptot = 3Vph Iphcos(Φ)):

30. ptot = 3(VL/√3)ILcos(Φ)

Since

31. 3 /√3 = √3

We can express equation 30 as

32. ptot = √3VLILcos(Φ) ; Total Active Power (using Line values) for a balanced three-phase system (Wye Circuit).

where VL and IL are RMS values.

For a Delta Connection:

33. VL = Vph

34. IL = √3Iph

35. Iph = IL /√3

Substitute these into equation 26 (ptot = 3Vph Iphcos(Φ))

37. ptot = 3VL (IL /√3)cos(Φ)

Since

38. 3 /√3 = √3

39. ptot = √3VLILcos(Φ) ; Total Active Power (using Line values) for a balanced three-phase system (Delta Circuit).

where VL and IL are RMS values.

Summary of Power Equations

19. P = Vrms Irmscos(Φ); Single-phase AC circuit Standard Average Power Equation

26. ptot = 3Vph Iphcos(Φ); Total Active Power (using Phase values) for a balanced three-phase system (applies to both Wye or Delta circuits).

32. and 39. ptot = √3VLILcos(Φ) ; Total Active Power (using Line values) for a balanced three-phase system (applies to both Wye or Delta circuits).

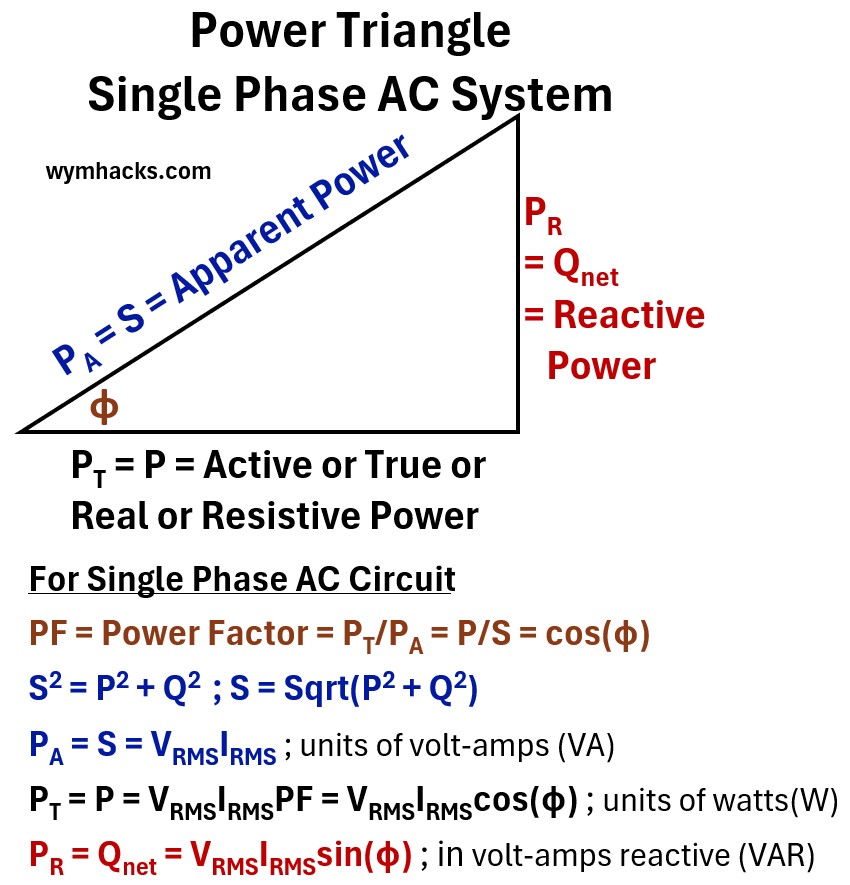

Single Phase AC Power Triangle

The equations derived in the previous sections—specifically P = VrmsIrmscos(Φ) and P = √3VLILcos(Φ)—all solve for Active (or Real or True) Power (P).

While these formulas give us the numerical value of the work being done, it is important to remember that they represent only one side of the electrical story.

In an AC circuit, Active Power is the “Real” power.

It is the energy that is permanently consumed by the load and converted into useful output, such as

- the rotation of a motor shaft,

- the heat of an element, or

- the light from a bulb.

However, because most AC systems rely on magnetic fields to operate (like the windings in a motor or transformer), there is a second type of “power” at play that doesn’t show up in our P equations: Reactive Power.

Any single phase AC circuit, no matter how complicated, can be described with a power triangle and it looks like the picture below.

We reviewed this in depth in my post AC Circuits: I-V Relationships, Impedance, Admittance, and Power

Picture: Power Triangle For Single Phase AC System

where

PA = S = Apparent Power

- The total “theoretical” power delivered to a circuit, representing the product of voltage and current without considering the timing difference between them

PT = P = Active / True / Real / Resistive Power

- The actual power that performs useful work or generates heat, representing the portion of energy truly consumed by the load.

PR = Qnet = Reactive Power

- The “non-working” power that oscillates back and forth between the source and the load to maintain magnetic or electric fields.

φ = phase angle

- Angular difference between the Voltage sine wave and the Current sine wave.

- The displacement in time, measured in degrees or radians, between the peaks of the voltage and current sine waves.

PF = Power Factor = PT/PA = P/S = cos(φ)

- A ratio between 0 and 1 that represents the efficiency of power usage, calculated as the fraction of apparent power that is converted into real work.

S2 = P2 + Q2 ; S = Sqrt(P2 + Q2)

- The geometric relationship based on the Pythagorean theorem showing that apparent power is the vector sum of real and reactive power.

PA = S = VRMSIRMS ; units of volt-amps (VA)

- The formula for total power capacity measured in volt-amps (VA), calculated by multiplying the effective voltage and current.

PT = P = VRMSIRMSPF = VRMSIRMScos(φ) ; units of watts(W)

- The formula for the actual wattage consumed, which scales the total power by the efficiency of the phase alignment.

PR = Qnet = VRMSIRMSsin(φ) ; in volt-amps reactive (VAR)

- The formula for the reactive power measured in VAR, representing the component of power that is 90 degrees out of sync with the voltage.

VRMS = Root Mean Square Voltage

- The effective AC voltage value that produces the same heating effect as an equivalent DC voltage.

IRMS = Root Mean Square Current

- The effective AC current value representing the steady-state equivalent flow of charge over time.

RMS = Root Mean Square

- A mathematical method used to calculate the “effective” magnitude of a varying waveform, like a sine wave.

- See my post: RMS (Root Mean Square) of a Sinusoid

Let’s now construct the power triangle for a three phase AC balanced circuit.

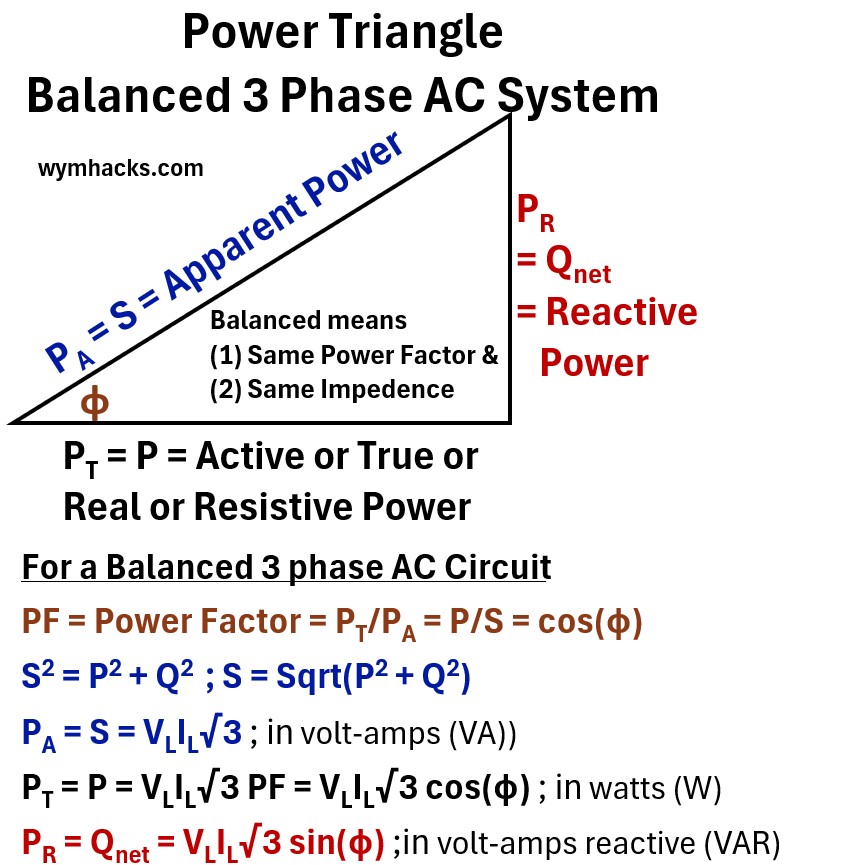

The Three-Phase AC Power Triangle

Moving from a single-phase understanding to a three-phase system is a logical progression.

Think of it as moving from a single engine cylinder to a perfectly timed three-cylinder engine.

Here is the step-by-step sequence to bridge that gap.

Step 1: Define the Balanced 3-Phase Set

In a balanced three-phase system, you have three separate “phases” (A, B, and C).

Each phase behaves exactly like a single-phase circuit, but they are mathematically offset:

- Each phase has the same RMS Voltage and RMS Current.

- Each phase is shifted by 120° from the others.

- Each phase has the exact same Power Factor cos(Φ).

Step 2: Calculate Total Real Power (P)

Since the system is balanced, the total real power is simply the sum of the power in each of the three phases.

Note we did the same thing the “three Phase AC Power Derivations” section above.

- Power of one phase: Pph = (Vph )(Iph )(cos(Φ))

- Total Power: P = 3(Vph )(Iph )(cos(Φ))

Step 3: Relate Phase Values to Line Values

In the real world, we usually measure Line Voltage (VL) and Line Current (IL) because those are the terminals we can actually access.

Depending on the connection (Wye or Delta), a √3 factor appears: (see the “three Phase AC Power Derivations” section for how)

- In Wye (Star): VL = √3 (Vph ) and IL = Iph

- In Delta: VL = Vph and IL = √3 (Iph )

Step 4: Substitute and Simplify

Whether the system is Wye or Delta, when you substitute the Line values back into the total power equation

- PTotal = 3(Vph)(Iph)cos(Φ), the math results in the same constant:

- P = √3VL ILcos(Φ); (as we showed in the “three Phase AC Power Derivations” section)

Step 5: Apply the Same Logic to Q and S

Because the phase shifts and magnitudes are identical for reactive and apparent power, the √3 constant applies to them as well:

- Reactive Power: Q =√3VLILsin(Φ)

- Apparent Power: S = √3VLIL

Step 6: Construct the 3-Phase Power Triangle

Now, take these three new values (P, Q, S) and place them back into the triangle.

- The horizontal leg is P (Total Watts).

- The vertical leg is Q (Total VAR).

- The hypotenuse is S (Total VA).

The relationship S2 = P2 + Q2 remains perfectly intact because you have scaled every side of the triangle by the same factor

- 3 relative to phase values, or √3 relative to line values).

And voila, we see that we can derive a three phase power triangle which is simply a scaled up version of its single phase triangle.

where

PA = S = Apparent Power

- Apparent Power (PA or S): The hypotenuse, measured in volt-amperes (VA).

- This is the total power that the wires, transformers, and generators must be sized to carry.

- PA= S = √(P2 + Q2)

PT = P = Active / True / Real / Resistive Power

- The base of the triangle, measured in watts (W).

- This is the horizontal component that performs actual work.

- P = PT = (S)cos(Φ)

PR = Q = Qnet = Reactive Power

- The vertical side, measured in volt-amperes reactive (VAr….or VAR).

- This power oscillates between the source and the load to maintain magnetic fields.

- it performs no actual work but is necessary for the system to function.

- Q = Qnet = PR = (S)sin(Φ)

φ = phase angle

- Angular difference between the Voltage sine wave and the Current sine wave.

PF = Power Factor = PT/PA = P/S = cos(φ)

- The Power Factor tells us how efficiently the system is converting the total supplied energy into useful work.

S2 = P2 + Q2 ; S = Sqrt(P2 + Q2)

PA = S = √3VLIL ; units of volt-amps (VA)

PT = P = √3VLILPF = √3VLILcos(φ) ; units of watts(W)

PR = Qnet = √3VLILsin(φ) ; in volt-amps reactive (VAR)

Line terminals

- In a three-phase system, VL and IL refer to the measurements taken at the “Line” terminals

- They are the actual wires connecting the source to the load.

VL = RMS Line Voltage

IL = RMS Line Current

- RMS = Root Mean Square

- A mathematical method used to calculate the “effective” magnitude of a varying waveform, like a sine wave.

- See my post: RMS (Root Mean Square) of a Sinusoid

The Conclusion

The “geometry” of the triangle does not change when moving from single-phase to three-phase.

The only thing that changes is the scaling factor.

You are effectively stacking three identical single-phase triangles together to form one larger, balanced 3-phase triangle.

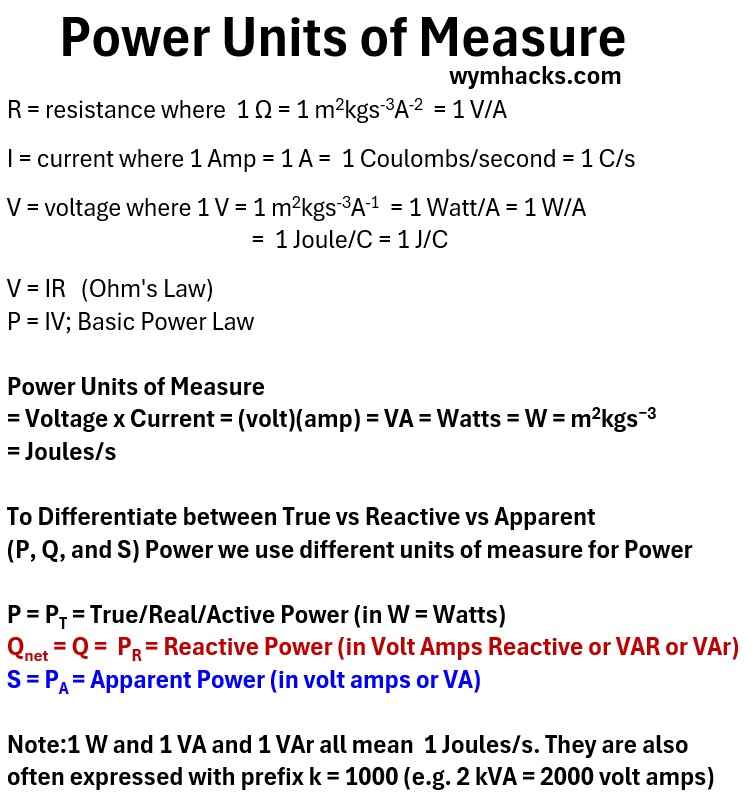

Let’s Get Clear on Electric Power Units of Measure

While the power triangle distinguishes between Active, Reactive, and Apparent power to highlight their different roles in a circuit, they all share the same fundamental physical dimension: energy per unit time.

Because power is the product of voltage and current, the basic unit for all three is technically the watt (1 W = 1 Joule/second).

However, to avoid confusion and clearly signal which component of the power triangle is being discussed, engineers use distinct labels:

- Watts (W) are reserved for Real or Active power (P or PT ),

- Volt-amperes reactive (VAR or VAr) are used for Reactive power (Q = Qnet = PR), and

- Volt-amperes (VA) denote Apparent power (PA = S).

Picture: Electrical Power Units of Measure

In industrial and utility-scale applications, the quantities involved are so large that the metric prefix “k” (kilo) is standard, resulting in kW, kVAR (or kVAr), and kVA (representing 1,000 units each).

This shorthand allows professionals to instantly recognize whether a measurement refers to the

- power performing actual work,

- the “magnetizing” energy oscillating in the system, or

- the total combined burden on the electrical infrastructure.

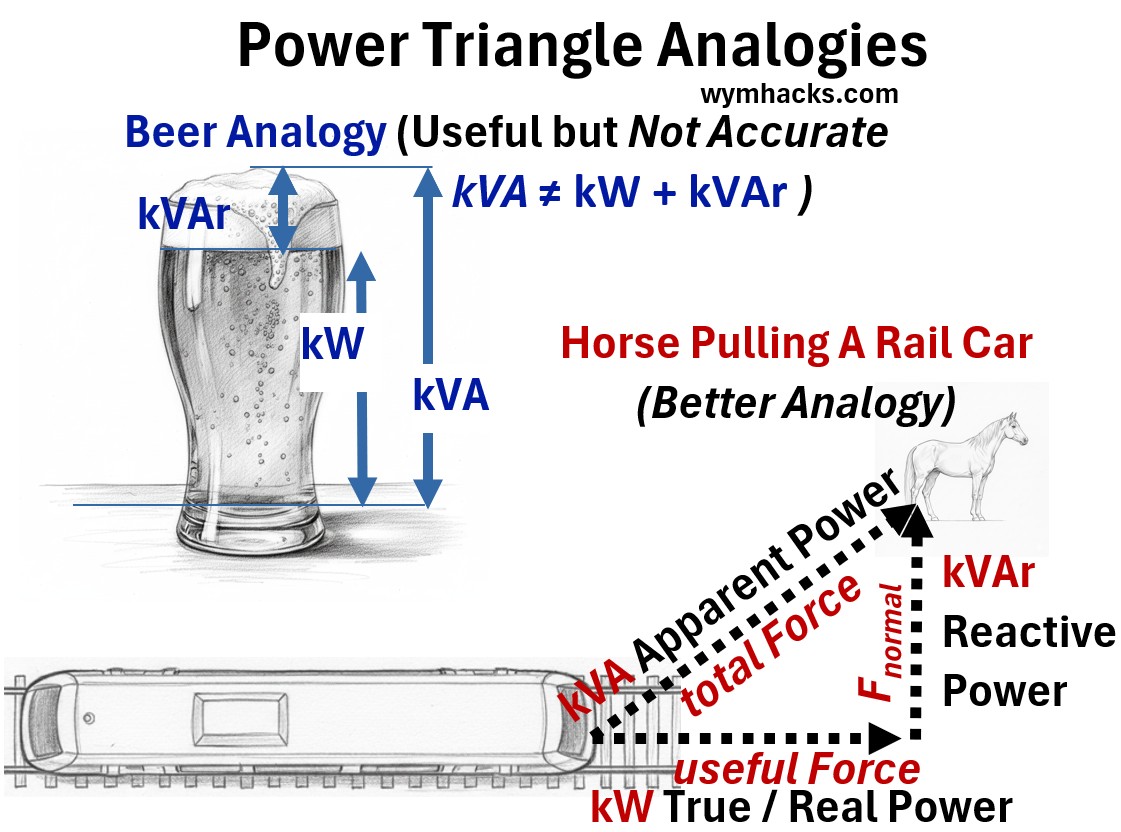

Electrical Power Analogies: Beer vs. Physics

To help conceptualize why we have “extra” power that doesn’t do work, we can look at two common analogies.

One simple but flawed analogy is the beer glass with foam on top.

The other is a more accurate analogy of a horse pulling a rail car at an angle.

Picture: Power Triangle Analogies

The Beer Glass Analogy (The Flawed Comparison)

You may have seen the “Beer Analogy” used to explain power factor.

In this visualization,

- the liquid beer is the Active Power (the part you want),

- the foam is the Reactive Power (the part you don’t want),

- and the glass is the Apparent Power (the total capacity).

This might help for general understanding but it fails the math.

In a beer glass, the foam and liquid add up linearly (Liquid + Foam = Glass).

But as our derivations show, power adds vectorially.

You cannot simply subtract the “foam” from the “glass” to find the “beer”; you must use the Pythagorean theorem.

Furthermore, foam is just waste, whereas in many AC circuits, Reactive Power is a physical necessity to keep motor magnets energized.

The Horse and Railcar Analogy (The Accurate Physics)

A much more accurate representation is a work and force problem.

Imagine a horse pulling a railcar along a track, but the horse is walking on a path alongside the tracks rather than between the rails.

Active Power (P): This is the horizontal force pulling the railcar forward.

Only the force aligned with the direction of motion performs Work (Work = Force x Distance).

Reactive Power (Q): This is the perpendicular force pulling the car toward the side of the track.

Because the car cannot move sideways, this force performs zero work.

However, it is a physical reality of the setup—the horse cannot pull the car forward without also exerting this sideways tension.

Apparent Power (S): This is the total tension in the rope.

The horse has to exert this full amount of effort, and the rope must be strong enough to handle it, even though not all of that effort results in forward motion.

This analogy perfectly illustrates the Power Factor:

- as the horse walks closer to the track (reducing the angle Φ),

- the “sideways” force (Q) decreases, and

- more of the total tension (S) is converted into forward-moving “Active” power (P).

Power Equations in Unbalanced Three Phase Systems

The concept of a single, unified power triangle—where you can calculate everything using one line current, one line voltage, and a fixed √3 multiplier—remains perfectly valid for both Delta and Wye configurations, provided the system is balanced.

In these cases, the geometry of the triangle stays identical regardless of the connection;

- only the internal math for how you reach the “sides” of that triangle changes

- e.g., in Wye, Vph = VL/√3, whereas in Delta, Iph = IL/√3

However, the moment the system becomes unbalanced, the symmetry that allows for a single “shortcut” formula collapses.

In an unbalanced system, the standard power triangle no longer represents the whole system at once;

- instead, it becomes a mathematical summary of three separate, unique triangles—one for each phase.

- You must calculate the individual real and reactive powers for each leg first, sum them up, and

- then construct a “total” power triangle from those aggregates to find your overall apparent power and system power factor.

Check out these two unbalanced system examples by by Zack hartle.

Disclaimer: The content of this article is intended for general informational and recreational purposes only and is not a substitute for professional “advice”. We are not responsible for your decisions and actions. Refer to our Disclaimer Page.