Menu (linked Index)

Electricity (2/11) – Mathematical Foundations

Last Update: January 15, 2026

Introduction

This is the second installment in a series of posts on electricity.

If we want to understand electricity, we have to first familiarize ourselves with the language of physics

- This chapter establishes the mathematical and measurement standards necessary for precise scientific communication.

- It covers the essential tools of the trade, from SI units and notation to the vector concepts that define how physical fields occupy space.

- All the mathematical concepts used in this series on electricity are provided in a bottoms-up, linked outline at the end of this section.

Navigation Index to Electrical Series Posts

Navigate to other posts in this series from the linked index below.

Electricity_(1/11 ) Introduction

Electricity_(2/11 ) Mathematical Foundations

Electricity_(3/11) Motion and Force

Electricity_(4/11) Energy, Work, and Power

Electricity_(5/11) Electrostatics, Current and Voltage

Electricity_(6/11) Electric Field, Magnetic Field, Current, And Voltage Relationships

Electricity_(7/11) Circuits, Resistors, Inductors, and Capacitors

Electricity_(9/11) AC Theory

Electricity_(10/11) Power Systems and the Grid

Electricity_(11/11) Timeline of Key Developments in Electromagnetism

On Line References

Listen, I could have easily listed 100 good references here.

There are indeed many on line references linked in many of my posts.

Here are a few I figured you should definitely have at your fingertips.

The first two are just good references for you to keep your units of measure straight.

The khanacademy.org link houses probably the greatest collection of STEM related videos, taught buy several amazing teachers.

Finally, my “best of teachers” listing , gives you a certainly incomplete list of some amazing teachers that post their videos for free on the web.

- Symbols, Units, Nomenclature and Fundamental Constants in Physics – IUPAP 2010 – by Cohen and Giacomo

- NIST Office of Weights and Measures: www.NIST.gov SI units

- https://www.khanacademy.org/

- The Best On-Line Teachers

SI Base and Derived Units (Quantities)

The International System of Units (SI) provides the standardized framework required for precise physical measurement and calculation.

This section defines the seven fundamental base units and demonstrates how they are mathematically combined to form derived units such as the Newton, Joule, and Watt.

These are essential for quantifying mechanical and electrical phenomena.

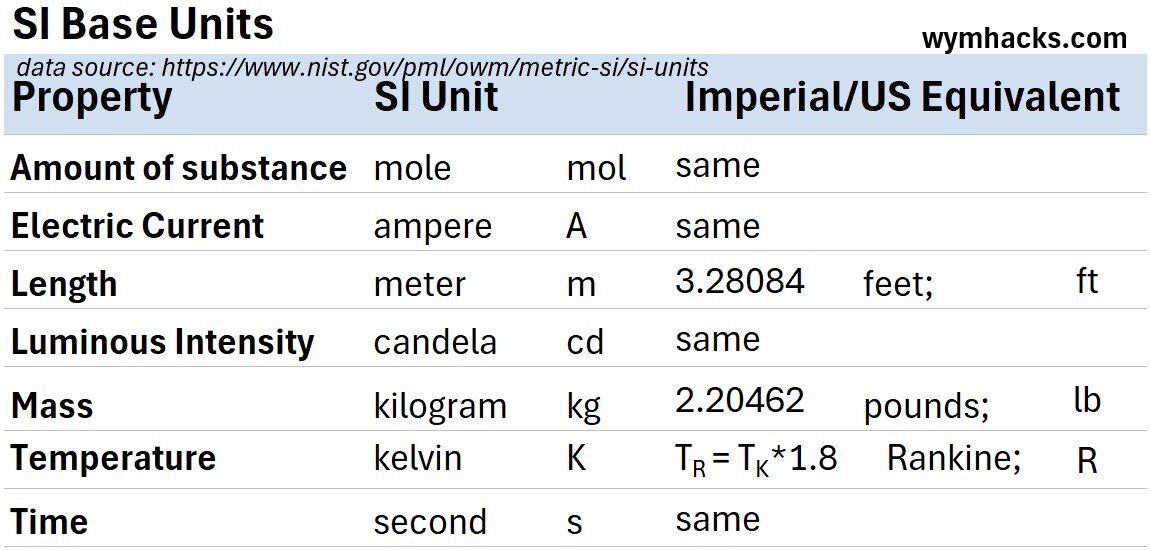

SI (International System of Units) defines seven base units which are

Time: second = s

Length: meter = m

Mass: kilogram = kg

Current: ampere = A = coulomb/s = C/s

Temperature: kelvin = K

Mole: mol

Candela: cd

I provide a few more details on Amperes and Temperature below.

You can review my post SI Base Units for more details.

You can also review some additional SI Related tabulations and charts in this post.

Regarding Amperes

The ampere is the unit of measure for electrical current.

- Current is the flow of electrons or charge.

- Flow of electricity along a wire conductor is current.

Its magnitude is set by fixing the numerical value of the elementary charge to be equal to exactly 1.602176634 x 10-19 coulombs (C)

Elementary Charge = 1.602176634 x 10-19 coulombs (C)

- The coulomb has SI units of As [ampere seconds],

Per NIST (adopted 2019), “The ampere is a measure of the amount of electric charge in motion per unit time ― that is, electric current.

But the quantity of electric charge by itself, whether in motion or not, is expressed by another SI unit, the coulomb (C).

One coulomb is equal to about 6.241 x 1018 electric charges (e).

One ampere is the current in which one coulomb of charge travels across a given point in 1 second.”

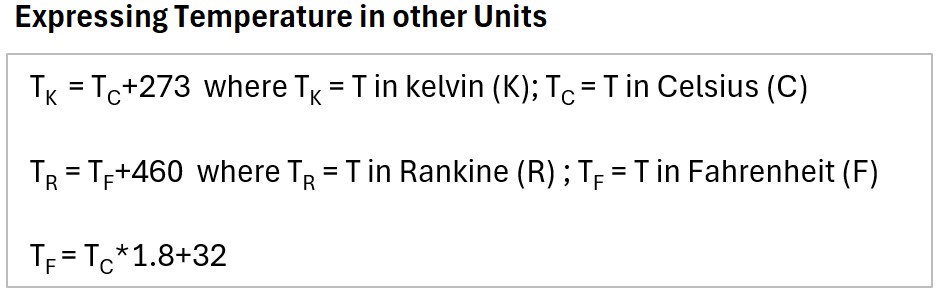

Regarding Temperature

- TK = TC +273 where TK = T in kelvin (K); TC = T in Celsius (C)

- TR = TF+460 where TR = T in Rankine (R) ; TF = T in Fahrenheit (F)

- TF = TC *1.8+32

Table: Expressing the SI Base Temperature in Other Units

Base Units

- Base Units are Independent Physical Quantities:

- They represent a distinct and independent physical quantity.

- They are irreducible dimensions of physical phenomena.

The table below shows the SI base units and the equivalent Imperial/US units.

Table: SI Base Units and Their Equivalent Imperial/US Units

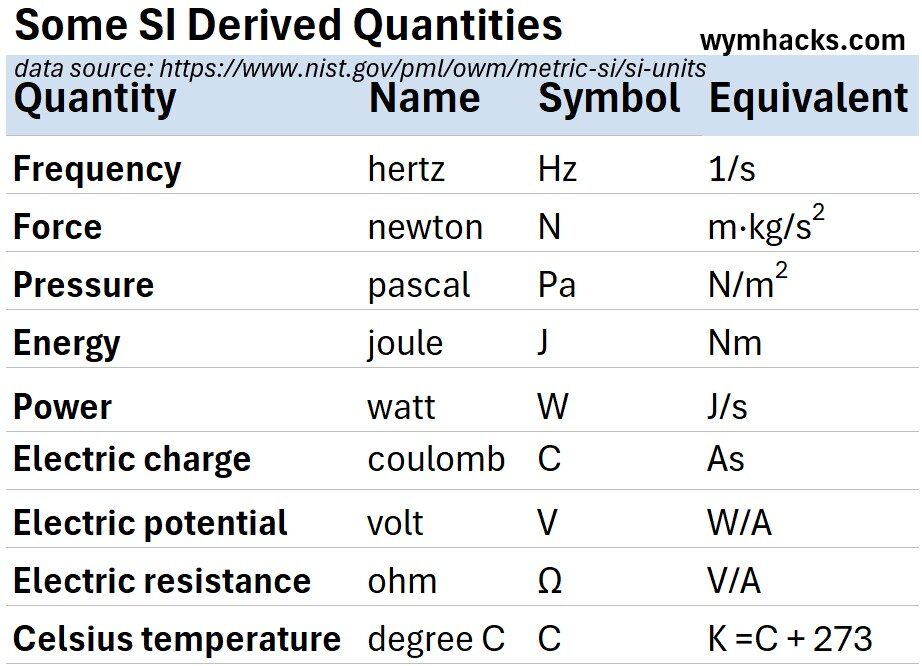

Derived Units

Table: SI Derived Quantities and Units

For a more complete tabulation of derived units you can check out my post: SI Base and Derived Units Tables and Charts

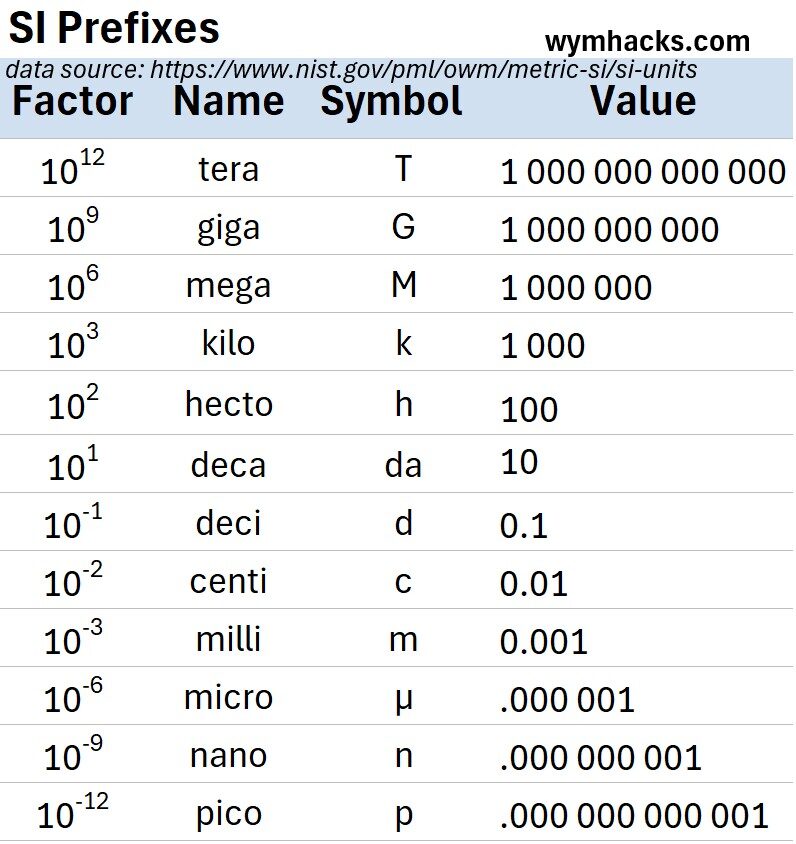

Numerical Prefixes

I list some metric SI prefixes in the table below.

For example, 1 picometer = 1×10-12 meters.

Table: Some Metric SI Prefixes

Order of Operations (PEMDAS)

Order of math operations – Khanacademy.org

- Parenthesis,

- then Exponents,

- then Multiplication/Division

- then Addition/Subtraction.

Example: 50−2×(3+5)2÷8

Step_1: Parentheses: First, solve the operation inside the parentheses.

- 50 − 2×(8)2÷8

Step_2: Exponents: Next, solve the exponent.

- 50 − 2×64÷8

Step_3: Multiplication and Division (equal priority; from left to right)

- 50 − 128 ÷ 8 = 50 – 16

Step_4: Subtraction

- 50−16=34

Math Notation

Basic Math Symbols

- / = division sign; e.g. a/b = a divided by b

- * or “no space” = multiplication; e.g. a*b = ab = a times b

- “x” can also be the multiplication sign but to avoid confusion we will use * or “no space”

Exponentiation

- xy = x raised to the y power; e.g. r2 = r squared= rr = r*r

- x-y = one over x raised to the y power = 1/xy

- e.g. r-2 = 1/r2

- e.g. a-3b2 = (1/a3)b2

“Times 10 to the power of” Notation

Scientific Notation

- Known as the standard form,

- “x 10y” means times 10 to the power y

- e.g. 245,000 = 2.45 x 105

- e.g. 23,400,000 = 23.4 x 106

- e.g. .00234 = 23.4 x 10-4

E (or e) Notation

- is short hand for “times 10 to the power of”.

- e.g. 245,000 = 2.45e5 = 2.45E5 = 2.45 x 105

- e.g. 1e6 = 1E6 = 1,000,000 = 1 x 106

- e.g. 1e-3 = 1E-3 = .001 =1 x 10-3

Engineering Notation

- is a type of scientific notation where the exponent is always a multiple of 3.

- e.g. 245,000 = 245E3 = 245 x 103

See wikipedia.org for more on scientific notation.

Vectors and Scalars

According to Google Gemini, “a vector is

- a mathematical object that possesses both a magnitude (a non-negative real number representing its “strength” or “length”) and

- a direction (an orientation in space).

It can be represented geometrically as a directed line segment (an arrow) where

- the length of the arrow indicates its magnitude, and

- the way the arrow points indicates its direction.”

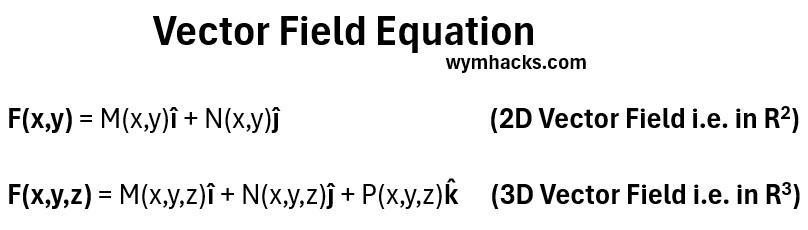

Have you seen those cool wind weather maps?

A lot of them display wind direction and magnitude with vector lines where shape and arrow show direction and the length indicates magnitude.

Picture: A Hypothetical Wind Vector Map for Texas

Some more examples of where vectors are used are:

Kinematics and Dynamics

- Describing motion (kinematics) and the causes of motion (dynamics) relies heavily on vectors.

- Displacement, velocity, and acceleration are all vector quantities.

- Forces are vectors; when multiple forces act on an object, vector addition (superposition) is used to find the net force and predict the object’s resulting motion.

- Without vectors, we couldn’t accurately model projectile motion, circular motion, or the complex interplay of forces in an engineered structure.

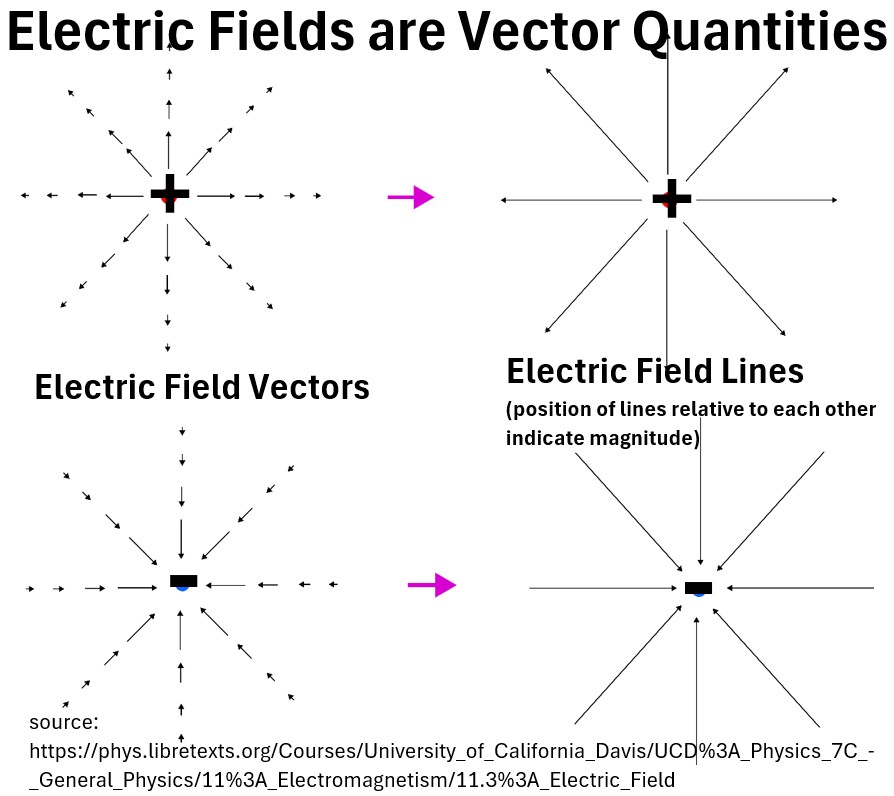

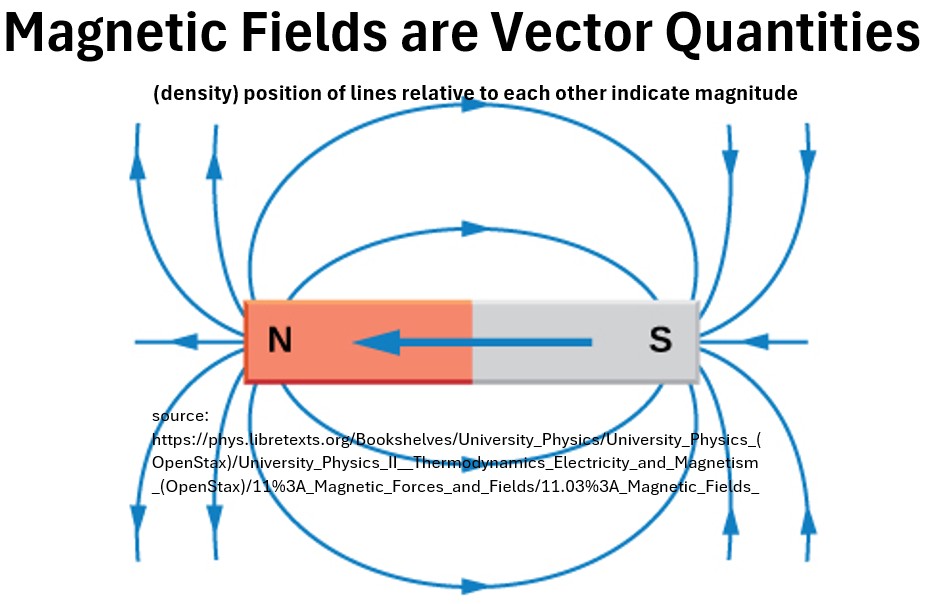

Electromagnetism

- Electric fields and magnetic fields are defined at every point in space with both a magnitude and a direction.

Picture: Electric Field Vectors and Lines

Picture: Magnetic Field Lines

- Vector calculus, with operations like gradient, divergence, and curl, is indispensable for understanding how these fields originate from charges and currents, how they interact, and how electromagnetic waves propagate.

- Maxwell’s equations, which unify electricity and magnetism, are expressed most elegantly and powerfully in vector form.

Fluid Dynamics , Quantum Mechanics, etc.

Vector Basics: What is a Scalar?

A scalar only has magnitude (size).

Example: Speed as measured in meters/second.

Vector Basics: What is a Vector?

A vector has magnitude (size) and direction.

Example 1: Velocity has magnitude meters/second but also has a specified direction.

Example 2: Force has magnitude (measured in units of Newtons) and direction.

Vector Basics: Adding, Subtracting, and Multiplying Vectors

Check out my post on vector math to see how vectors can be added, subtracted, and multiplied (dot or cross).

Also check out these nice video tutorials on basic vector math:

Fields

This section is excerpted from my post on fields and field operators: Field Operators: Grad, Div, and Curl

In the sciences, a field represents a region of space where a physical quantity or mathematical value is assigned to each point.

- A field is a function that assigns a value (scalar or vector) to each point in a space.

- In physics, fields describe forces and influences extending through space and time, like gravity or electromagnetism.

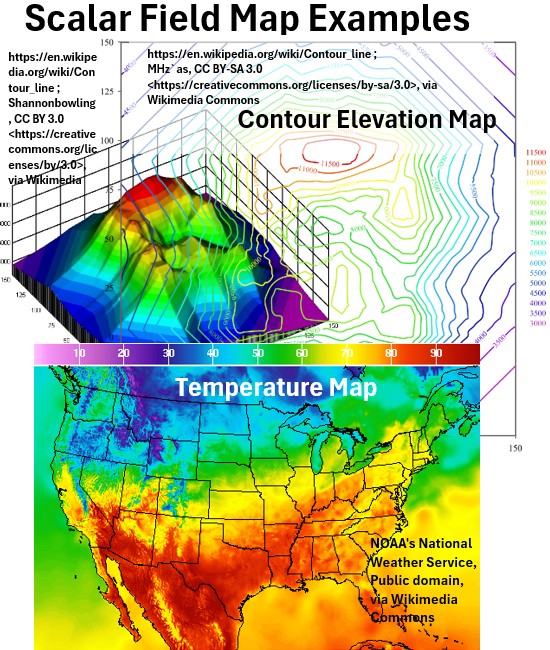

Scalar Field (Scalar Field Function)

When the domain of a scalar function is a region in space (e.g., 2D or 3D physical space, or a surface), the scalar function effectively defines a scalar field.

A scalar field function is a type of scalar function that assigns a single scalar value to every point in a space,

Essentially, a scalar field is a specific application of a scalar function where the domain is a spatial region.

A generalized scalar field function, F, in three-dimensional space can be written as:

f(x,y,z)=C

where:

- x, y, and z are the coordinates of a point in space.

- C is a scalar value (a single number) assigned to that point.

For example, a scalar field could represent

- the temperature at every point in a room, where

- the function f(x,y,z) gives a single temperature value at a specific location.

Other examples of Scalar Fields:

- Elevation contour map

- Pressure distribution

- Density (mass/volume) distribution

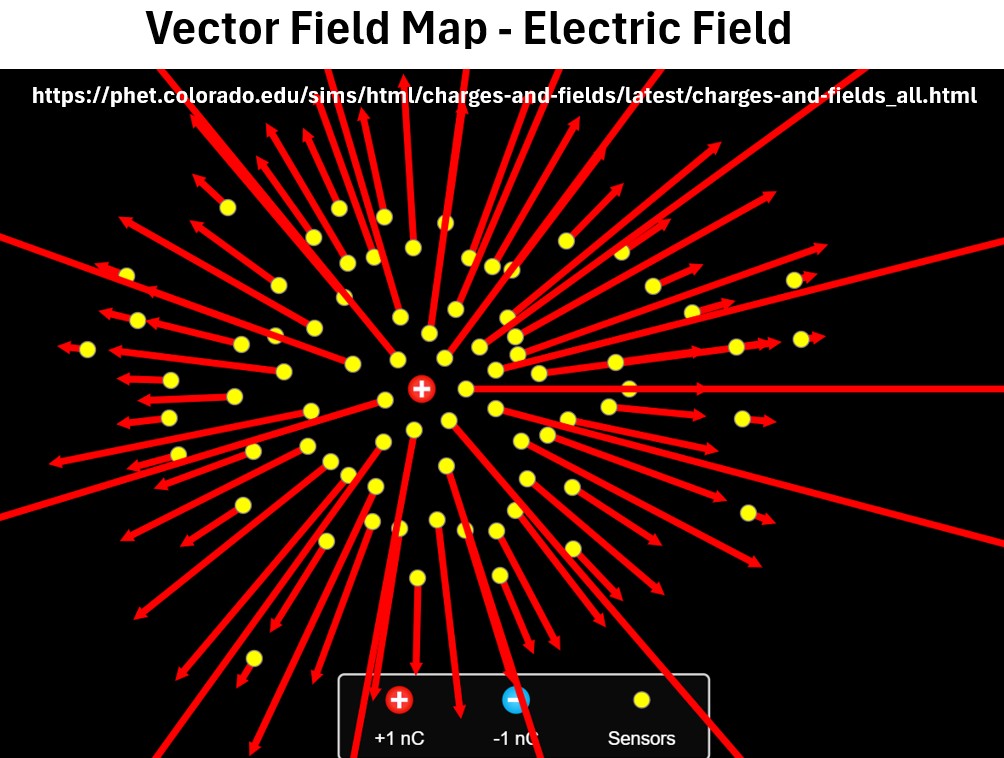

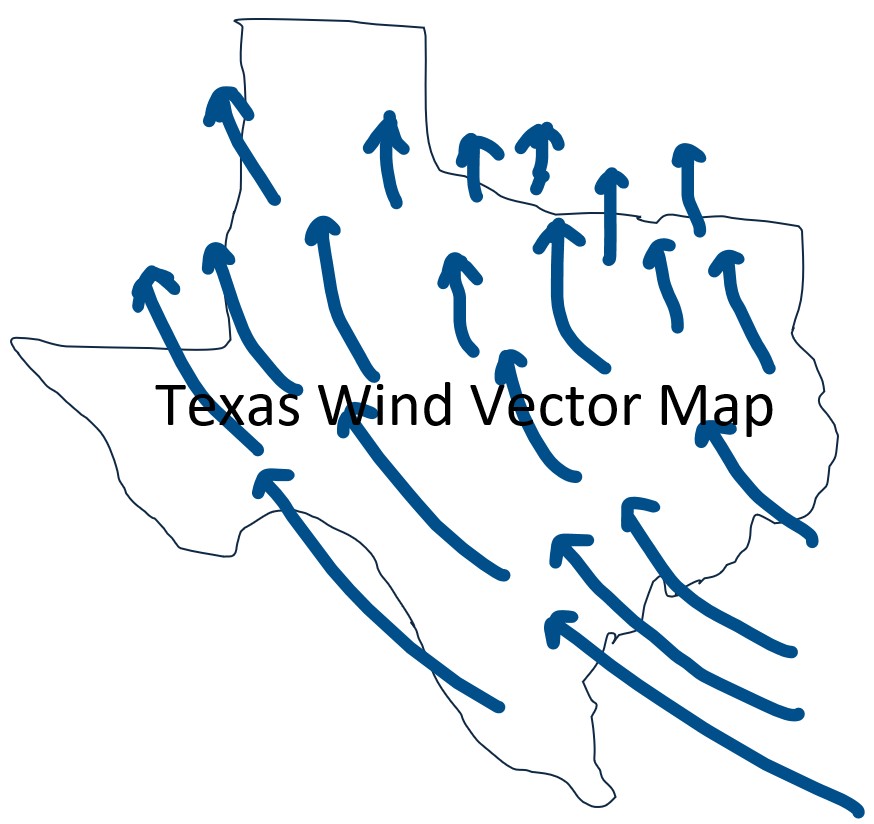

Vector Field (Vector Field Function)

A vector field function maps points in an n-dimensional space to vectors in that same n-dimensional space. e.g. 2D to 2D

A generalized vector field function, F, in three-dimensional space can be written as:

F(x,y,z)=M(x,y,z)î + N(x,y,z)ĵ + P(x,y,z)k̂

where:

- x, y, and z are the coordinates of a point in space.

- î, ĵ , k̂ are the standard unit vectors along the x, y, and z axes.

- M, N, and P are scalar-valued functions that describe the components of the vector at each point.

For example, a vector field could represent the velocity of wind at every point over Texas,

- where M, N, and P would describe the x, y, and z components of the air’s velocity at that location.

In 2D, we would only have the x,y space and the î and ĵ unit vectors, and so the vector equation becomes:

F(x,y)=M(x,y)î + N(x,y)ĵ

That wind map of Texas shown in the previous section is an example of a vector field.

Vector Field Example: Wind Velocity and Direction Weather Map

Vector Field Example: Electric Field From A Single Positive Charge (Source: PHET)

In the electric field map above, notice how the vectors all point out symmetrically and radially from the source charge.

Math Foundations Outline With Links

In the previous sections I described a select number of important mathematical concepts, sufficient for us to continue our learning journey.

There will be several more mathematical concepts (e.g. differentiation, integration etc.) that will be introduced as we continue this series of posts on electricity.

I thought it would be useful though, to have all the key math concepts covered in this series to be listed in one place.

I’ve done this with the outline below (with links to connect you to the post of interest).

(1) The Basic Language (Arithmetic & Units)

What numbers are and how we measure the physical world

Understand the basic Hierarchical order of numbers (Defining Reals, Rationals, etc.)

The standard language of measurement

Scaling between systems

(2) Geometry and Trigonometry (Spatial Logic)

This level builds the circular and periodic logic required for higher-level physics and complex math.

Basic shapes and fundamental identities

The transition from degrees to circular measure

Understanding periodic oscillations

Rotational Motion

Crucial algebraic tools for later derivations

(3) Direction and Change (Vectors & Calculus)

Moving from static values to values that have direction and “rate of change.”

Manipulating magnitudes with direction

The math of instantaneous change

The math of accumulation; the inverse of the derivative

(4) The Complex Plane and Euler

Unifying trigonometry and exponential growth using “imaginary” numbers.

Introduction to the Complex (a + bi) Plane

Operations within the complex plane

Understanding the base of natural growth

Using trig and e to derive Euler’s Formula and Euler’s Identity [ eix = cos x + i sin x] and [eiπ =−1]

(5) Advanced (Circuit Analysis, Fields & Signals)

Circuit Analysis Math

Applying calculus to vectors in 3D space

Breaking down complex waves into sine/cosine components using Euler’s Formula and Integration

Disclaimer: The content of this article is intended for general informational and recreational purposes only and is not a substitute for professional “advice”. We are not responsible for your decisions and actions. Refer to our Disclaimer Page.