Menu (linked Index)

Electricity (3/11) – Motion and Force

Last Update: January 15, 2026

Introduction

This is the third installment in a series of posts on electricity.

Before exploring electromagnetism, this chapter grounds the reader in the classical laws of motion and the fundamental interactions that govern the universe.

By exploring mass, acceleration, and gravity, we get the necessary mechanical context to later compare gravitational fields with electric ones.

Navigation Index to Electrical Series Posts

Navigate to other posts in this series from the linked index below.

Electricity_(1/11 ) Introduction

Electricity_(2/11 ) Mathematical Foundations

Electricity_(3/11) Motion and Force

Electricity_(4/11) Energy, Work, and Power

Electricity_(5/11) Electrostatics, Current and Voltage

Electricity_(6/11) Electric Field, Magnetic Field, Current, And Voltage Relationships

Electricity_(7/11) Circuits, Resistors, Inductors, and Capacitors

Electricity_(9/11) AC Theory

Electricity_(10/11) Power Systems and the Grid

Electricity_(11/11) Timeline of Key Developments in Electromagnetism

On Line References

Listen, I could have easily listed 100 good references here.

There are indeed many on line references linked in many of my posts.

Here are a few I figured you should definitely have at your fingertips.

The first two are just good references for you to keep your units of measure straight.

The khanacademy.org link houses probably the greatest collection of STEM related videos, taught by several amazing teachers.

Finally, my “best of teachers” listing , gives you a certainly incomplete list of some amazing teachers that post their videos for free on the web.

- Symbols, Units, Nomenclature and Fundamental Constants in Physics – IUPAP 2010 – by Cohen and Giacomo

- NIST Office of Weights and Measures: www.NIST.gov SI units

- https://www.khanacademy.org/

- The Best On-Line Teachers

Length, Mass, and Weight

Length

- Length: distance from end to end

- Various symbols can be used to indicate length, for example,

- l (length),

- d(diameter),

- r(radius or distance), etc.

- SI unit of measure: meter = m

Mass and Weight

Mass and Weight – Khanacademy.org

- Mass: How much stuff or matter an object has.

- Mass: Won’t change depending on location.

- Mass: How something responds to a given force.

- Mass symbol is typically m.

- Don’t confuse an equation symbol like m for mass with the SI unit for length = m (for meter).

- SI unit for mass = kg = kilogram = 1000 grams = 1000 g

- In physics we differentiate between what is meant by mass versus weight.

- Weight is the force of gravity on an object (which has a mass). See Force section below.

Velocity and Acceleration

Velocity

- Velocity Measures how quickly the position of an object changes.

- Velocity is a vector (has magnitude and direction)

- v = velocity

- SI Units: meters/second = m/s

Acceleration

- Acceleration is the rate of change of velocity.

- Acceleration is a vector quantity.

- a = acceleration

- SI Units: (m/s)/s = meters/(seconds squared) = m/s2

Force

A Force is an influence that can cause an object with mass to accelerate (change its velocity) or deform.

- A force is a push or pull on an object.

- It is a vector quantity with magnitude and direction.

- F = force

F = mass*acceleration= m*a = ma

- Known as Newton’s Second Law (or Law of Acceleration)

- Acceleration is directly proportional to the net force acting on it and inversely proportional to its mass.

- The direction of the acceleration is in the direction of the net force.

- SI Units for force: 1 newton = 1N = 1 kilogram-meter per second squared = kgm/s2

Newtons Three Laws of Motion

These three laws, formulated by Sir Isaac Newton in his Principia Mathematica (1687), laid the groundwork for classical mechanics and remain essential for understanding motion in the universe.

Newton’s First Law (Law of Inertia)

- An object at rest stays at rest, and

- an object in motion stays in motion

- with the same speed and in the same direction,

- unless acted upon by an unbalanced force.

Newton’s Second Law (The Law of Acceleration)

The acceleration of an object is

- directly proportional to the net force acting on it and

- inversely proportional to its mass.

- The direction of the acceleration is in the direction of the net force.

Fnet = m*a = ma = (mass)(acceleration)

Fnet = the net force (the vector sum of all forces acting on the object), measured in Newtons (N).

Newton’s Third Law (The Law of Action and Reaction)

For every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction.

e.g. A bird’s wings push air downwards and backward (action). The air pushes the bird upwards and forwards (reaction), generating lift and thrust

Gravitational Force & Gravitational Potential Energy

For a nice introduction to this topic see Sal Khan’s video on gravity.

Universal Law of Gravitation (Newton)

- Gravitational force acts at a distance.

Fg = G(m1)(m2)/r2 ; Gravitational Force

- Fg = gravitational force

- G= universal gravitational constant = 6.67e-11 Nm/kg2

- m1, m2 = mass of objects 1 and 2

- r = distance between objects (don’t confuse with radius)

- Gravitational Force Equation for object on earth

- Fg = G(m1)(m2)/r2

- Let m1 = mass of earth and m2 = m = mass of object on earth where

- m1 = mass of earth = ~5.97e24 kg

- r = distance from center of object on surface (or “near surface” of earth to center of the earth = ~6378 km)

- so, Gm1/r2 = [(6.67e-11 Nm/kg2)(5.97e24 kg)]/(6378 km)2 = g = ~ 9.8 m/s2

Fge = mg = Gravitational Force between earth and object with mass m (with g constant w/ r near 6378 km)

- g = acceleration of gravity for earth (~9.8 m/s2)

- Note: g as a constant of about 9.8 m/s2 is only valid when the r value is approximately the earth’s radius

- So, it’s ok to apply to “negligible heights”.

- Even up to a plane’s flying altitude which is about 6378/(6378+10) = .2% greater than the earths radius,

- but not for a satellite in orbit or a spacecraft etc.

- Example: Weight is a gravitational force

- If somebody has a mass of 70 kg, then

- his/her weight = Fge = 9.8 m/s2 * 70 kg = 686 kgm/s2 = 686 Newtons = 686 N

Gravitational Potential Energy

Gravitational potential energy is the energy an object possesses due to its position within a gravitational field.

If you assume that the force is constant then,

work = force x distance so, Gm1m2/r2 * r = Gm1m2/r

PEg = Gm1m2/r ; Gravitational Potential Energy

If you didn’t assume the force was constant then you would have to do a little calculus to arrive at the same equation.

Read my post Work and Energy to see how this is done.

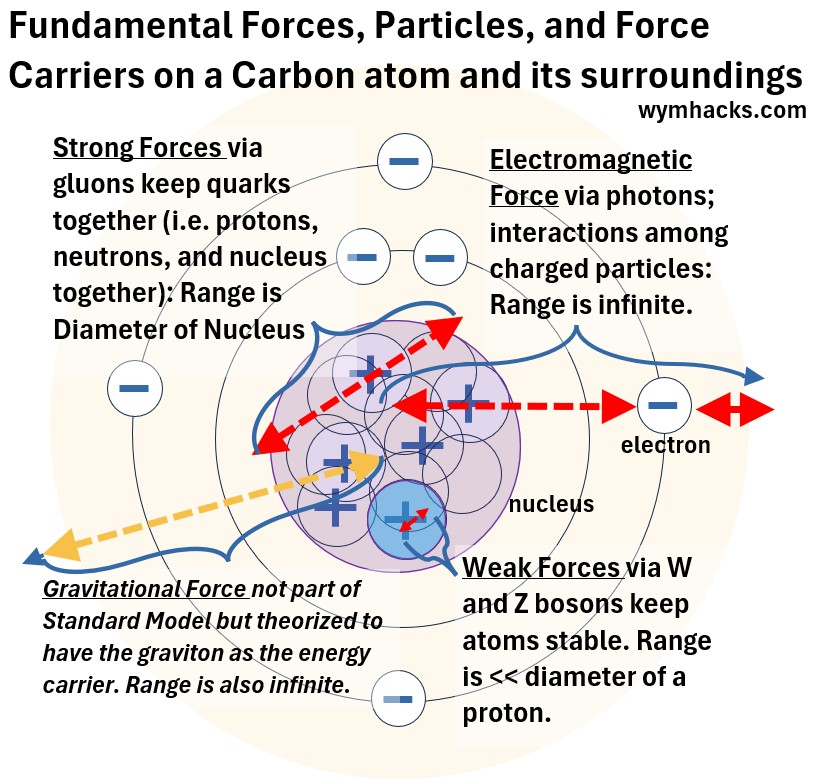

The Four Fundamental Forces

In additional to gravitational force there are three other forces recognized and defined by physicists.

To describe these, we need to first understand the Standard Model of Particle Physics.

I wrote a separate more detailed post on the Standard Model which you can access via this linked title: Fundamental Particles and Forces

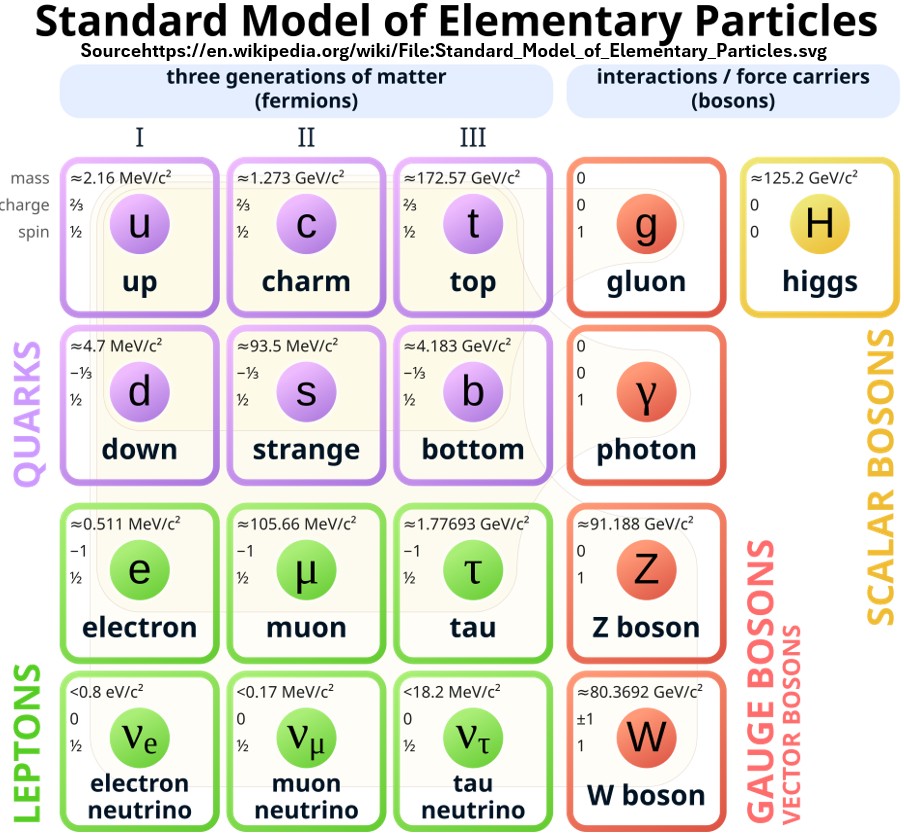

Standard Model

The Standard Model describes

- the fundamental particles (quarks, leptons, and their antimatter counterparts) and

- three of the four fundamental forces (strong, weak, and electromagnetic) that govern how they interact,

- all mediated by force-carrying particles (bosons) and with the Higgs boson providing mass.

- It notably excludes gravity.

Building Blocks of Matter

- All matter is made of elementary particles that are one of two types: quarks or leptons.

- Quarks and leptons each consist of six types of particles.

- The six types are related in pairs, or “generations”.

Forces

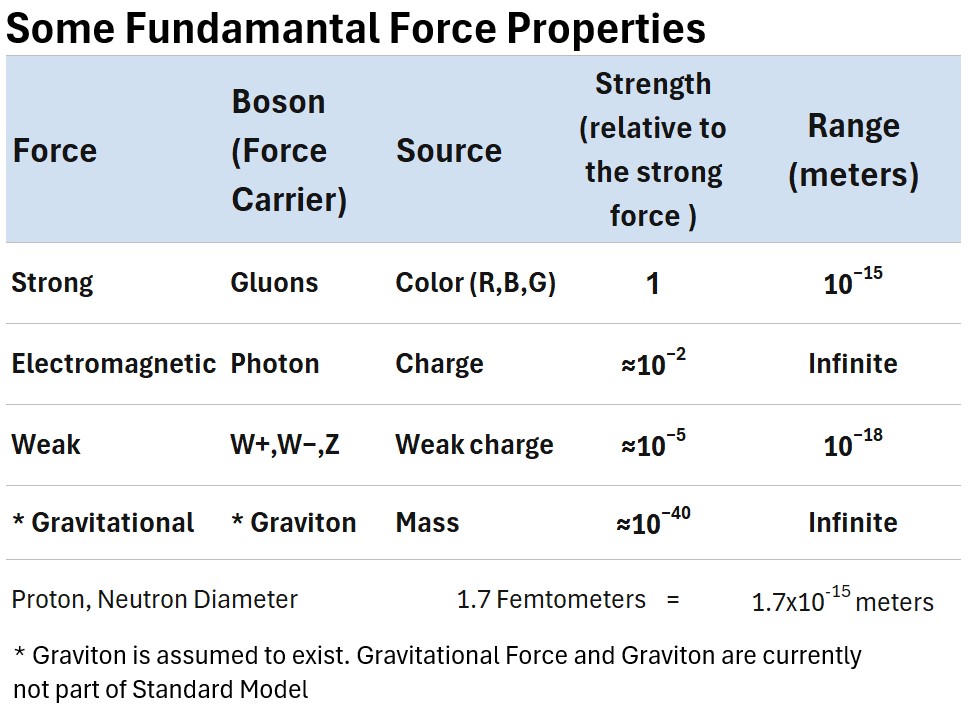

There are four fundamental forces at work in the universe:

- the strong force,

- the electromagnetic force,

- the weak force, and

- the gravitational force.

They work over different ranges and have different strengths.

- Gravity and electromagnetic force have infinite range.

- The weak and strong forces are effective at subatomic levels .

- The forces from weakest to strongest are: gravity, the weak force, the electromagnetic force, and the strong force.

Force Carriers

- Three of the fundamental forces result from the exchange of force-carrier particles, which belong to a broader group called “bosons”.

- Particles of matter transfer discrete amounts of energy by exchanging bosons with each other.

- Each fundamental force has its own corresponding boson –

- The Standard Model includes the electromagnetic, strong and weak forces and all their carrier particles, and explains well how these forces act on all of the matter particles.

- However, the most familiar force, gravity, is not part of the Standard Model.

Physicists believe that all these forces come from one underlying force.

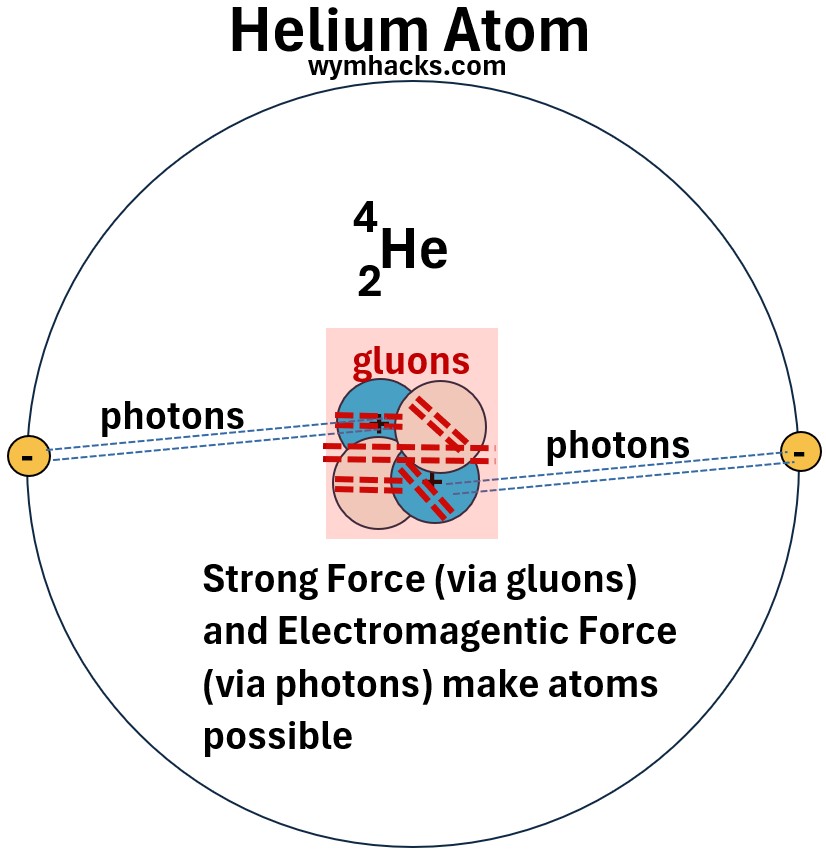

The Strong Force

- The strongest force carrier is the gluon.

- The strong force is 100 times stronger than the Electromagnetic Force.

- It keeps the protons (and neutrons) together in the nucleus (like Velcro).

Picture: A Proton: The Strong Force Carrier Gluons Keep Quark Particles together

- The Strong Force is only effective at small scales (the width of a proton).

- It’s this kind of energy that is released from nuclear bombs.

Electromagnetic (EM) Force

- The EM force carrier is the photon.

- Electromagnetic Forces are 1036 times the Gravitational Force.

- They are 10 to 12 times stronger than the Weak Force.

- But, these forces attract and repel and so will tend to cancel each other.

- On a macroscopic scale (like a planet, star, or even a human body), the vast majority of matter has a net electric charge of zero.

- i.e. in the universe you don’t see large collections of charged forces like you do mass concentrations (and therefore gravitational forces)

- EM forces comprise the Electrostatic (Coulomb Force) and the Magnetic Force.

- Electricity and Magnetism are fundamentally interconnected phenomena, where a changing electric field creates a magnetic field and a changing magnetic field creates an electric field.

- EM waves are generated by accelerating charges.

- EM waves are perpetually produced as each change in one produces the other (and they can travel in a vacuum).

- Electromagnetic (electrostatic and magnetic) forces extend infinitely far away (like gravity).

- Electrostatic force (Coulomb’s law)

- Fe = kq1q2/r2

- Fe = electrostatic force

- k = coulomb’s constant

- q1, q2 =The quantity of charge of objects 1 and 2

- r = distance between the charges.

- Magnetic forces also generally follow an inverse square law.

- EM forces are responsible for the nature of light.

- EM forces allow atoms to exist , keeping electrons bound to nuclei.

Picture: Gluons and Photons Allow Atoms to Exist (Example Helium Atom)

- EM Forces are the basis of all chemistry.

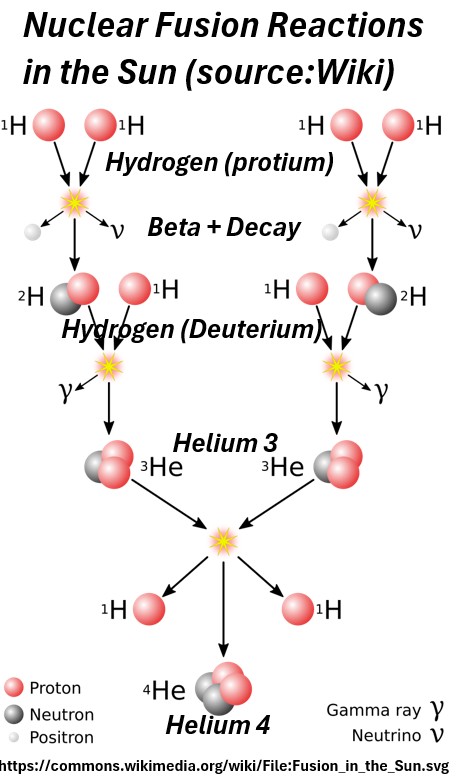

The Weak Force (The Weak Interaction)

- The weak force carriers are the W and Z bosons.

- The weak force is 1025 times the strength of gravity.

- It’s only effective at really small scales (1/1000 the diameter of a proton).

- Responsible for radioactive decay. (beta minus or beta plus decay)

- Example: Cesium decay

- Cs → Ba + electron + anti-electron neutrino

- Cesium 137 has 137 nucleons (protons + neutrons)

- It’s Cesium because it has exactly 55 protons.

- One of the Neutrons (a quark flips) turns into a proton

- The element now has one extra proton (56 total) and is now Barium.

- An electron and an anti-electron neutrino are produced.

- Beta plus decay in Nuclear Fusion gives us energy and light from the sun

Picture: Beta Plus Decay in Solar Nuclear Fusion

Gravitational Force

- Gravity is not included in the Standard Model.

- It’s theorized that its force carrier is the graviton but this has not been proven.

- It’s the weakest of the forces.

- Gravity keeps you “glued” to earth and keeps the planets in orbit.

- It is an attractive force.

- For all practical purposes Newton’s Law of Gravitation describes gravity

- Fg = G(m1)(m2)/r2

- Fg = gravitational force

- G= Universal Gravitational Constant

- m1, m2 = mass of objects 1 and 2

- r = distance between objects

- Gravitational Force extends infinitely far away.

The table below summarizes the relative strengths and ranges of the four fundamental forces.

Table: Comparing Forces and Force Carriers

I annotated the Wiki Standard Model chart below to show the range in which the various force carriers operate.

Picture: Fundamental Force Ranges Annotated on a Carbon Atom

Namely:

- Gluons operate at close distance and keep quarks together (and therefore protons and neutrons and nuclei together).

- The range of photons and W, Z Bosons (and the theoretical gravitons) are much wider

- The Higgs Field gives particles their mass

Disclaimer: The content of this article is intended for general informational and recreational purposes only and is not a substitute for professional “advice”. We are not responsible for your decisions and actions. Refer to our Disclaimer Page.