Menu (linked Index)

Electricity (5/11) – Electrostatics, Current, and Voltage

Last Update: January 15, 2026

Introduction

This is the fifth installment in a series of posts on electricity.

We introduce the stationary charge and the invisible “push” of the electric field.

It bridges the gap between static charges and moving ones, introducing the concepts of voltage and conductors that allow electricity to flow (current).

Navigation Index to Electrical Series Posts

Navigate to other posts in this series from the linked index below.

Electricity_(1/11 ) Introduction

Electricity_(2/11 ) Mathematical Foundations

Electricity_(3/11) Motion and Force

Electricity_(4/11) Energy, Work, and Power

Electricity_(5/11) Electrostatics, Current and Voltage

Electricity_(6/11) Electric Field, Magnetic Field, Current, And Voltage Relationships

Electricity_(7/11) Circuits, Resistors, Inductors, and Capacitors

Electricity_(9/11) AC Theory

Electricity_(10/11) Power Systems and the Grid

Electricity_(11/11) Timeline of Key Developments in Electromagnetism

On Line References

Listen, I could have easily listed 100 good references here.

There are indeed many on line references linked in many of my posts.

Here are a few I figured you should definitely have at your fingertips.

The first two are just good references for you to keep your units of measure straight.

The khanacademy.org link houses probably the greatest collection of STEM related videos, taught by several amazing teachers.

Finally, my “best of teachers” listing , gives you a certainly incomplete list of some amazing teachers that post their videos for free on the web.

- Symbols, Units, Nomenclature and Fundamental Constants in Physics – IUPAP 2010 – by Cohen and Giacomo

- NIST Office of Weights and Measures: www.NIST.gov SI units

- https://www.khanacademy.org/

- The Best On-Line Teachers

Charge and Electrical Force

An object has electric charge when it is able to be attracted or repulsed by another object.

The charge is a fundamental, inherent property of the subatomic protons and electrons.

Here are some nice introductory videos on charge:

- Triboelectric effect and charge – Sal Khan

- What is Electric Charge? (Physics – Electricity) – Edouard André Reny

- What Is Charge? – MIT – Krishna Rajagopal

Coulomb (Charge Quantity)

The coulomb is the unit of electric charge.

It is a quantity of electricity.

- C = coulomb

- 1 C is the quantity of charge in 6.24E18 electrons (or protons) = 6.24 quintillion electrons (or protons).

- A single electron (or proton), therefore has a charge of 1/6.241E18 = 1.602E-19 C, or, we can write

- e = Elementary Charge = 1.602E-19 C.

- Si unit: 1 C = 1 ampere-second = 1 As, where

- A = ampere (the unit of measure of current)

- s = second.

Coulomb’s Law

The interaction between charged objects acts as a force that acts over some distance between them.

The electrostatic force Fe is a component of one of the four fundamental forces of nature. (the Electromagnetic Force).

- Fe is very similar to the gravitational force: Fg = G(m1)(m2)/r2

- Like gravity, it acts at a distance.

- Fe , like Fg is a vector because it has force and direction

- Unlike gravity, which only attracts, an electrostatic force can attract or repel.

- The Direction of the Electric Force depends on whether two particles have like or opposite charges.

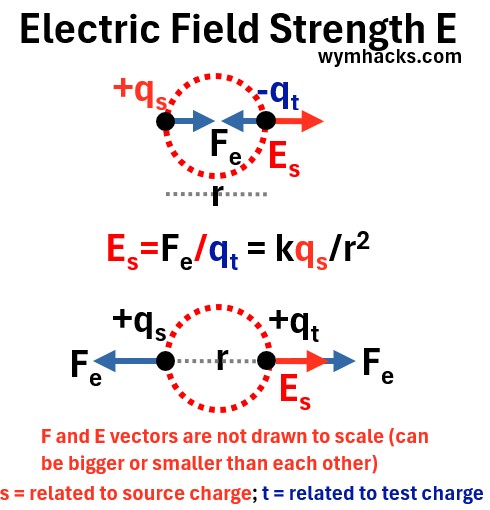

Picture: Electric Force Direction For Attractive and Repellent Charges

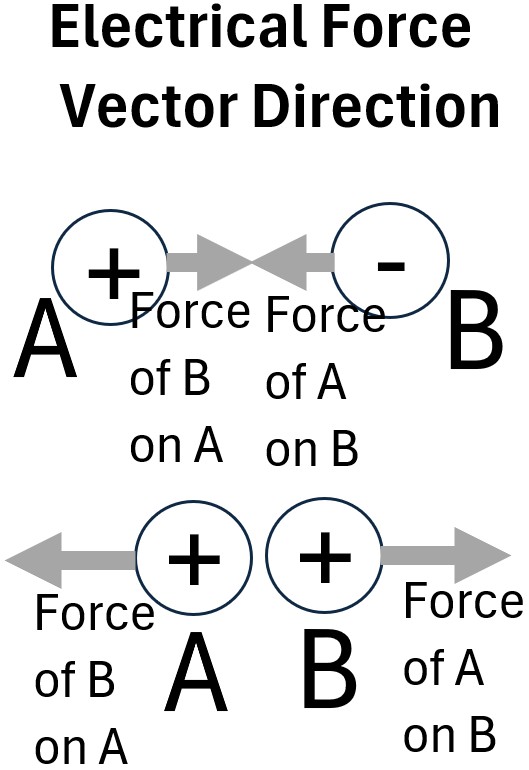

The magnitude or strength of the electric force between two charged particles is given by:

Fe = kq1q2/r2 ; Magnitude of Electric (Electrostatic) Force

- Fe = electrostatic force

- q1, q2 =The quantity of charge of objects 1 and 2

- F is positive when q1 and q2 are of like charge and negative when q1 and q2 are of opposite charge.

- r = distance between the charges.

- Notice the inverse square relationship between force and distance.

- k = 1/(4πε0) = coulomb’s constant

- ε0 = electric constant = electric permittivity of free space (i.e. a vacuum)

- ε0 = 8.854e-12 C2 / Nm2 or can use units of “F/m” or “s4A2/(m3kg)”

- k = 8.99e9 Nm2/C2

- F = farad

- 1 F = 1 s4A2/(m2kg) where

- A = ampere

- 1 A = 1 C/s

- m = meters

- kg = kilograms

In general Permittivity ε indicates how much a material resists the formation of an electric field within it.

- A material with high permittivity will oppose the formation of an electric field more strongly

- than a material with low permittivity.

ε0 is a measure of how dense of an electric field is “permitted” to form in response to electric charges (in a vacuum).

- ε0 is a measure of how “permissive” the vacuum of space is to the formation of an electric field (which are generated by electric charges).

- It (ε0) tells you the relationship between the amount of charge and the strength of the electric field it creates in empty space.

Check out these videos:

Electric Field and Electric Field Strength (Force/Charge)

The presence of a charged object will produce an electric field E.

An electric field is a region of space around a charged object where another charged object would experience a force.

The electric field is a vector quantity (has magnitude and direction).

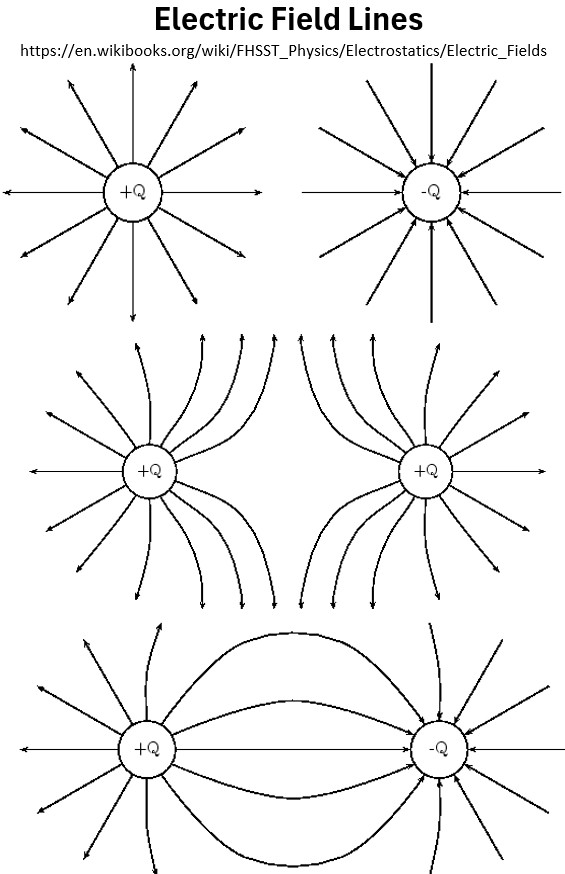

Ideal Electric fields not affected by other Electric fields are straight lines.

- They radiate outwards (if source charge is positive) and

- radiate inwards (if source charge is negative).

Attracting (opposite signs) and Repelling (same signs) field shapes are shown below.

Picture: Electric Charge Field Lines

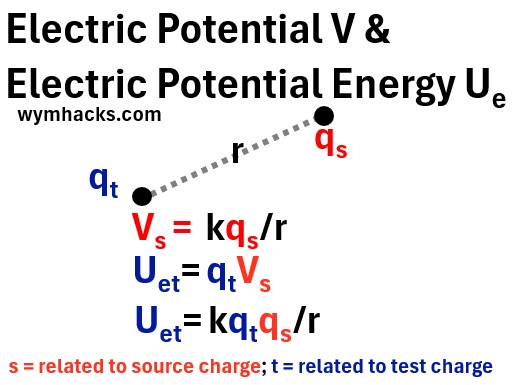

Another charged object entering an electric field (of a source charge) will experience an electric force Fe

Consider a charged object which is the source of the electric field, q1.

Consider another charged object q2 that enters the electric field produced by q1.

Starting with Coulomb’s Law:

Fe = kq1q2/r2

Divide by q2 to get the magnitude of the electric field E:

E = Fe/q2 = kq1/r2 ; magnitude of the electric field

- E = magnitude of the electric field = electric field strength = Force/Charge

- q1 = source charge (produces the electric field) = qs

- q2 = test charge (entering the electric field of q1) = qt

- k = coulomb’s constant

- SI units for E: Newtons/Coulomb = N/C

- Other SI units for E = Nm/Cm = Volts/meter = V/m

- N = newton

- C = coulomb

- V = voltage

- M = meter

Picture: Electric Field Magnitude

Here are some nice video lessons:

Electric Potential Energy (in Joules)

Electric potential energy is the energy a charged object possesses due to its position within an electric field.

Starting with Coulomb’s Law:

Fe = kq1q2/r2

where

- q1 is the source of the electric field and

- q2 is a charge in that field

- k = coulomb’s constant = 8.99e9 Nm2/C2

- r = distance between charge centers

Assuming the force is constant, multiply both sides by r:

Fer = Work = kq1q2/r = Energy in Joules

Electric Potential Energy PEe = Ue= kq1q2/r

If we assumed the force was not constant, we could derive the same equation using a little calculus.

See my post Work and Energy for the calculus derivation.

Here are some really nice video lessons you should watch.

Electric Potential (Joules/Coulomb = Volts)

Electric Potential is a Specific Energy

The electric potential at a point is the electric potential energy per unit positive charge that would be experienced by a test charge placed at that point.

The electrical potential will have units of energy per quantity of energy = Joules/Coulomb = J/C.

Start with the Electric Potential Energy equation:

Fer = W = Work = kq1q2/r = Electric Potential Energy PEe = Ue

where we assume q1 is the source of the electric field and q2 is a charge in that field.

Divide both sides by q2:

V = W/q2 = kq1/r = electric potential = (energy or work)/charge = EP in units of volts = J/C

The electric potential is a property of a single point in space within an electric field.

- It is a scalar value (magnitude only) that tells you the electric potential energy per unit of charge at that location.

- For an isolated charge or system, a reference point (often “infinity” where the potential is defined as zero) is chosen to calculate the potential at any other point.

- SI Units: Nm/C = J/C = volts = V

- q1= source of electric field

- q2= charge in the field of q1 = test charge = qt

- N = newton

- C = coulomb

- J = joules

- V = volts

From the above we can also state that

W = U = q2V = qtV = Potential Energy; Potential Energy of the charge qt

This is the work done by an external force to bring a test charge qt from a reference point (where V=0, usually infinity) to a specific point where the electric potential is V. This work is stored as the potential energy U of the charge qt

Electric Potential vs Electric Potential Difference

The electric potential has units of volts, but it should not be confused with the electric potential difference, or voltage, which also has volt units.

To avoid confusion, I’ll sometimes assign the following symbols to these terms:

- EP = electric potential (units of volts)

- Electric Potential is commonly represented by V

- To avoid confusing this with the unit of measure of voltage, I’m using EP.

- EPD = voltage = electric potential difference (also units of volts)

Electric Potential vs Electric Potential Energy

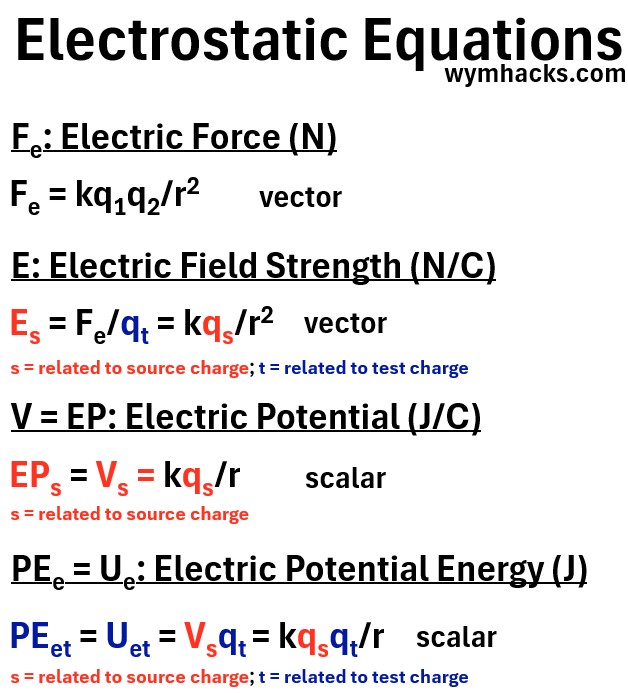

Let’s circle back to the relationship between the Electric Potential and the Electric Potential Energy.

See the picture below showing a test charge and a source charge (qt and qs) separated by distance r.

Picture: Electrical Potential V & Electrical Potential Energy U

The Electrical Potential Vs (at qt) is defined as:

Vs = kqs/r = Electrical Potential in units of Volts; (Work/Charge = Joules/Coulomb = J/C)

and the Electric Potential Energy is defined as:

Uet = qtVs = Electric Potential Energy in SI units of Joules (J); (C)(J/C) = J = Joules

Substituting for Vs , this becomes

Uet = kqtqs/r = Electric Potential Energy in SI units of Joules (J)

Excellent Video Lessons on Electric Potential:

- Electric potential at a point in space – Khanacademy – David SantoPietro

- Intro to electric potential – Khanacademy – Mahesh Shenoy

- Potential diff. & negative potentials

More on EPD (voltage) in the next section.

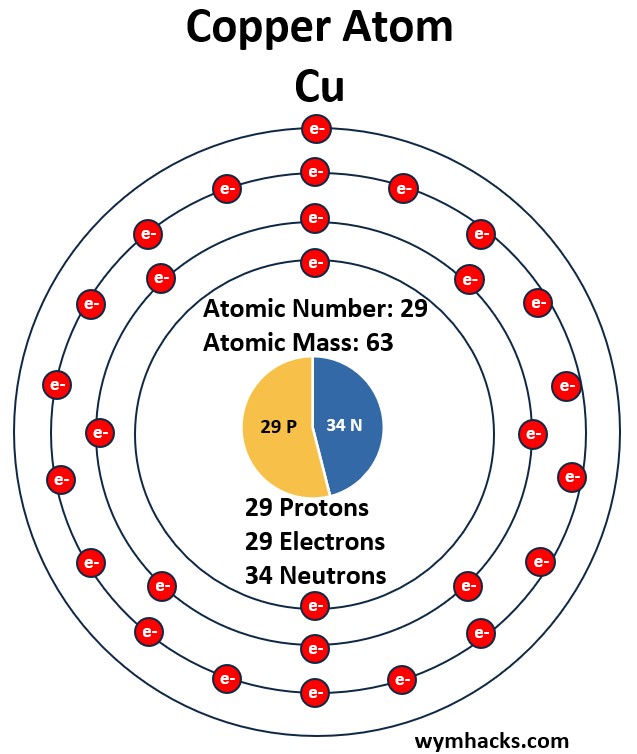

Conductors

A conductor is a material that allows electric charge to flow easily through it.

This property is due to its atomic structure, which contains loosely bound electrons in their outermost orbital energy shells.

The electrons can break free and become mobile charge carriers.

When a driving force is applied (i.e. voltage which is covered in a later section), these electrons move freely throughout the material, creating an electric current (more on current later).

Copper and silver are great conductors because they each have a single valence electron in their outermost shell that is weakly bound to the nucleus.

- The most electrically conductive metals, in order from highest to lowest conductivity, are: silver, copper, gold, and aluminum.

- Copper is mostly used due to its relative lower cost and abundance.

Picture: Copper Atom and its Single Valence Electron

Current: Direct Current / Alternating Current

Electric current is the rate of flow of electric charge past a point or region.

It is the movement of charged particles, such as electrons or ions, through an electrical conductor or space.

Electric current is the amount of charge that flows through a cross-sectional area in a given time interval.

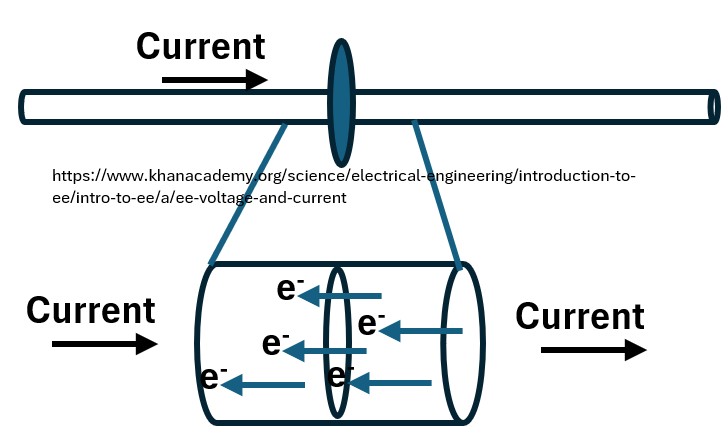

Consider the boundary depicted by the cross-sectional circle in the drawing below.

Picture: Current

Current would then be determined by counting how many charges per unit time pass through that boundary.

So, it can be expressed mathematically in differential form (i.e. instantantaneous ; i.e. dealing with infinitesimal changes) as:

I = i = dQ/dt; Current = Rate of change of charge with time

It means that electric current (I) is the instantaneous rate of flow of electric charge (Q) with respect to time (t)

- I = i = current (from the French description for current “Intensity”)

- Q = Electric charge

- Si unit for current: 1 ampere (A) = 1 coulomb/second = 1 C/s

- Si unit for charge: 1 Coulomb = 1 C = 1 As

In a circuit, if the current is 1 Ampere,

- then 1 Coulomb of charge passes a point in the circuit every second

Note that A and s are SI base units and C is considered an SI derived unit.

Note from the picture above (and below) that our convention for direction of current flow will be opposite the actual flow direction of electrons.

- Electric current – Khanacademy – Willy McAllister

- Electric current direction – Khanacademy – Willy McAllister

- Voltage – Khanacademy – Willy McAllister

- Conventional current direction – Khanacademy – Willy McAllister

Direct Current (DC)

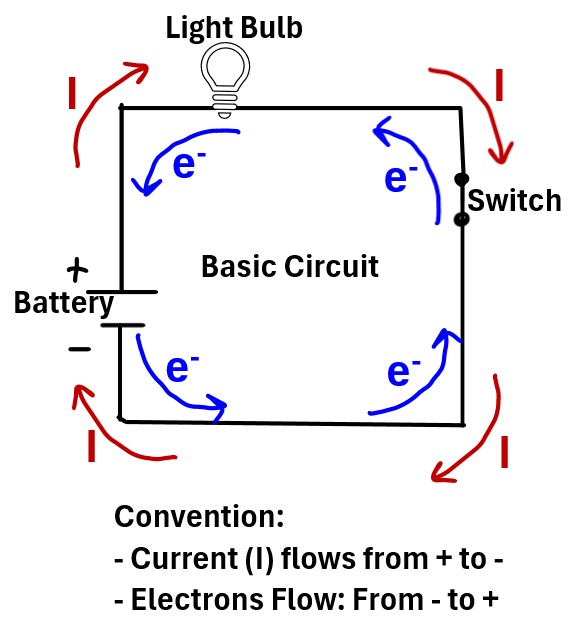

Direct current (DC) is the unidirectional flow of electric charge.

Its main characteristics are:

- Directional Flow: The flow of electric charge is constant and unidirectional,

- as opposed to alternating current (AC) which periodically reverses direction.

- The voltage remains at a constant polarity (i.e. a fixed positive and negative terminal).

- Common sources of direct current are

- batteries,

- solar panels, and

- fuel cells

- Application:

- DC is the standard for powering most electronic devices, including

- smartphones, computers, and electric vehicles.

- Conventional Flow Direction:

Picture: Conventional Current Flow (Current I is opposite of direction of electrons)

-

- (+ to -) : From the positive terminal of the power source, through the circuit, and to the negative terminal.

- This is the direction a positive charge would flow that is,

- It’s the opposite of the actual flow of electrons.

- You can thank Benjamin Franklin for this convention.

Alternating Current (AC)

AC is electric current that periodically reverses direction and continuously changes its magnitude.

Major Characteristics of AC:

- The direction of flow of the electrons periodically changes (switches back and forth).

- AC Frequency:

- The number of complete cycles (back and forth reversals) per second,

- measured in Hertz (Hz) (e.g., 60 Hz in North America, 50 Hz in Europe).

- AC Magnitude:

- The current’s strength continuously changes over time,

- typically in a sinusoidal (sine wave) pattern.

- Transformability:

- AC voltage can be easily stepped up or down using transformers,

- making it highly efficient for long-distance power transmission and distribution.

- Source of AC:

- The primary sources are Generator/Alternator systems where

- mechanical energy is converted into electrical energy based on the principle of electromagnetic induction.

- AC usage:

- AC is mostly produced in power generation plants.

- It is transmitted and distributed

- to households and commercial/Industrial facilities for various

- power applications e.g. motors and other machinery, lighting, heating, cooling, and electronics

See my posts below for more Alternating Current related articles:

- Sine and Cosine Definitions and Properties

- Electricity (9/11) AC Theory

- AC Circuits: I-V Relationships, Impedance, Admittance, and Power

- Alternating Current (AC) Generation

- AC Voltage and Current Equations

- Transformers

Excellent video tutorials on current

Voltage_(Work/Charge)

Voltage or electrical potential difference or EPD is a measure of the difference between electric potentials (EP) at two points.

- Recall that an electrical potential or EP describes the energy per charge at a specific location.

Voltage represents the electrical “pressure” or the energy available per unit charge to drive current between those two points.

- Electric current is the rate of flow of electric charge past a point or region.

- Voltage is sometimes described as an electromotive force.

- Voltage is work required to bring 1 Coulomb of charge from a lower electrical potential position to a higher electric potential position.

EPD = Electric Potential Difference = ΔV = voltage = Work/Charge = W/Q = J/C

- As I noted before typically V is the symbol for electric potential.

- So ΔV would be the electric potential difference.

- Confusing though since their unit of measure will also be volts = V

- So, sometimes I’ll use EP and EPD for electric potential and electric potential difference.

- SI unit (base units): (m2kg)/(s3A)

- SI unit (other SI units): J/C

Where

- m = meter

- kg = kilogram

- s = second

- A = ampere

- J = Joule

- C = Coulomb = 1 A/s

Note that (J/C) is energy per unit of quantity of charge which is somewhat analogous to the specific energy of a material (J/kg), the amount of energy per unit of quantity mass.

More on Electric Potential V vs Voltage Δ V

The symbols for both electric potential (V) and voltage (ΔV) are the same (V), which often leads to confusion.

The difference is that one is an absolute value at a point (relative to a reference) and the other is a difference between two points (absolute and physically relevant).

Electric Potential (V)

- Definition: Electric potential is the electric potential energy per unit charge at a single point in an electric field.

- Reference: It is always measured relative to an arbitrary, chosen zero-reference point (V=0). This reference is typically infinity (in theoretical electrostatics) or ground (in circuits).

- Analogy: Think of altitude on a map.

- If a point is at 100 meters, that value only makes sense because we’ve agreed that sea level is the 0 meter reference.

- If we chose the bottom of a nearby valley as our zero, the altitude of that point would change, but the physical location wouldn’t.

- Notation: In physics, this is often written simply as V (or ϕ).

Voltage (ΔV)

- Definition: Voltage is the Electric Potential Difference (ΔV) between two specific points, A and B. It is the work required to move a unit charge from point A to point B.

- Formula: ΔV=VB−VA.

- Physical Significance: Voltage is the driver of current flow; it’s the quantity that matters in all practical circuit applications.

- It is an absolute value—the voltage between two points remains the same no matter where you set your arbitrary zero-reference point.

- Analogy: Think of the difference in altitude between the top of a waterfall and the bottom. If the top is 100 m and the bottom is 70 m, the difference is 30 m.

- Even if you re-define sea level, the waterfall is still 30 m high.

- Notation: In engineering and circuits, this is almost always simply called Voltage and is often written as V (e.g., a 12 V battery) or ΔV.

If you want to learn about electrical science then these guys are your teachers.

Disclaimer: The content of this article is intended for general informational and recreational purposes only and is not a substitute for professional “advice”. We are not responsible for your decisions and actions. Refer to our Disclaimer Page.