Menu (linked Index)

The US Federal Budget Process (Last Update: February 12,2024)

If you want to take a look at a detailed breakdown of an actual completed budget, check out my article: The US Federal Budget – Part 2 – FY2022 Analysis.

Schematic 1.1 US Federal Budget Flow

![]()

- Introduction

- US Federal Budget Basics

- Key References, Laws, Terminology

- Budget Collections and Accounts (Using Example FY2022 Receipts)

- Controlling Laws and Spending Categories (Using Example FY2022 Outlays)

- Budget Process Participants

- Legislative Process

- US Federal Budget Phases (Overview)

- US Federal Budget Cycles/Timing

- Budget Process Phase 1 (Formulation)

- Budget Process Phase 2 (Enactment)

- Conclusion

- Appendix 1 – Reference Links and Glossary

- Appendix 2 – Congressional Committees

- Appendix 3 – Federal Government Agencies and Departments

- Appendix 4 – Federal Government Budget Functions

- Appendix 5 – House and Senate Voting Rules

- Appendix 6 – Federal Budget Process Performance

Federal Budget Process – Introduction

Many of you have and manage a budget i.e. a system of tracking the cash you bring in and the cash you spend.

A Budget (a way to track income and expenses) allows us to monitor and adjust our saving and spending behavior.

For the same reasons, the US Federal Government needs a system to manage its budget. It does this through an annual negotiation between the Executive Branch (The President) and the Legislative Branch (Congress) called the “US Federal Budget Process”. The required “products” of this process are legislative bills (laws) that influence and dictate practically all aspects of how the Government receives and spends money.

The purpose of this article is to:

- present and explain the relevant laws, organizations, terms and concepts that will aid in better understanding the Federal Budget Process.

- explain in detail the two “creative” phases of the Budget Process (Formulation and Enactment).

- present (assess) the historical performance of these two phases.

- give you a better appreciation of the complexities and challenges that our political leaders face when undergoing this annual exercise.

This article focuses on the budget process. If you want to take a look at a detailed breakdown of an actual completed budget, check out my article: The US Federal Budget – Part 2 – FY2022 Analysis.

Article Organization

The best way to read this article is from the top down. You can review the layout of the article from the linked index and go directly to the section you might be interested in, but, starting from the beginning and sequentially working through the topics is the way this article was designed to be read. The main topics covered are:

- Basic definitions of Budget, Receipt, Outlay, and Deficit

- The laws creating/defining the Budget Process and the key organizations that support it

- Government Collection and Accounts terminology (Receipts, General Funds and Trust Funds)

- Authorizing and Appropriations Laws and spending categories (Mandatory and Discretionary Outlays, and Business Functions)

- Budget Process Participants (OMB, CBO, GAO, Agencies, Congressional Committees etc.)

- A description of the legislative process (how Congress passes laws)

- A general overview of the Annual Budget Process

- Budget Process cycle timing (3 different budgets in different phases are occurring at any given time)

- Annual Budget Process details – Phase 1 – Formulation

- Annual Budget Process details – Phase 2 – Enactment

- Historical Performance of the Budget Process and General Observations / Recommendations.

The Appendices Are Full of Good Information

I’ve provided lots of informative (hyper-linked) references throughout the article, so don’t hesitate to check those out for more information (and access to budget data).

- You can utilize the big glossary in Appendix 1 if you need to clear on definitions.

- Refer to the other appendices at the end of this article to learn more about congressional committees (Appendix 2), agencies and departments (Appendix 3), Budget Functions (Appendix 4), legislative voting rules (Appendix 5), and a historical performance assessment of the Budget Process (Appendix 6).

As you read through the article please note that

(1) Unless specifically noted, “Government” refers to the US Federal Government.

(2) FY stands for Fiscal Year. e.g. FY2022 means Fiscal Year 2022 which ran from October 1, 2021 to September 30, 2022.

(3) Assume Budget Resolution and Concurrent Budget Resolution are synonymous.

Let’s jump in.

Budget Basics

A simple equation describing a budget is

- Budget = Receipts (incoming cash like taxes) – Outlays (expenditures like Department of Defense spending)

Schematic 3.1 shows a more complete high level view of the Federal Budget Process.

Schematic 3.1 – US Federal Budget: Receipts – Outlays = (+)Surplus or (-) Deficit

The US Federal Budget cash inflows (Receipts) and cash outflows (Outlays) will cause three possible scenarios:

- A “perfect balance” where Receipts = Outlays (this has never happened)

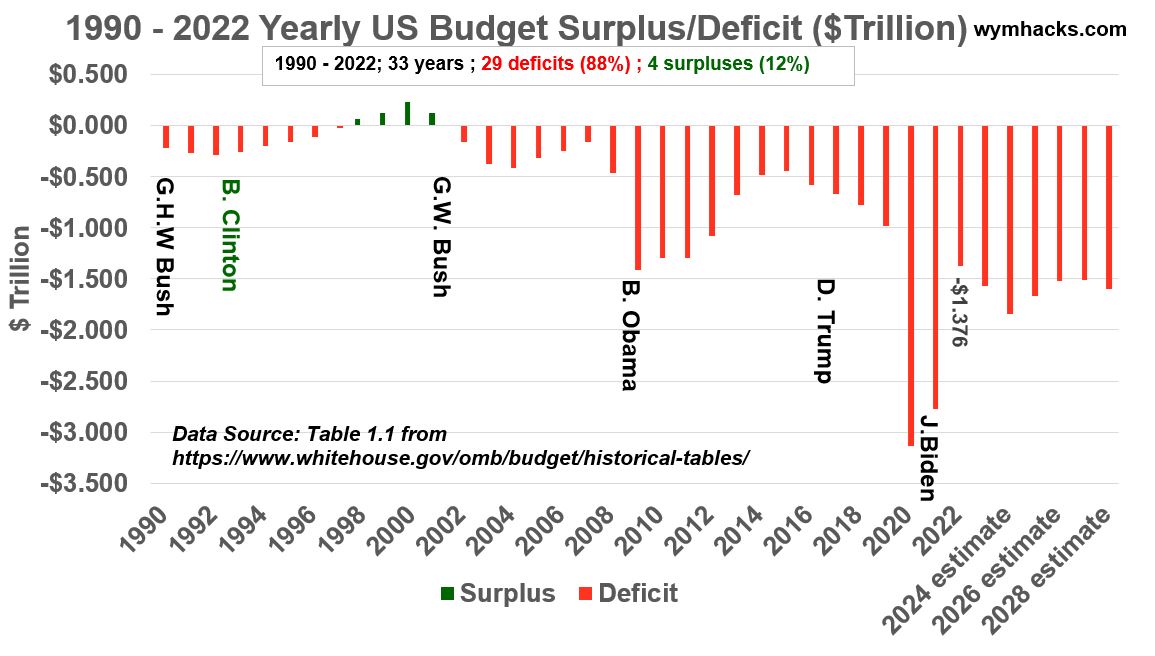

- A “surplus” where Receipts exceed Outlays. Since 1990, it has happened 4 times i.e. 12% of the time! (*)

- A “deficit” where Outlays exceed Receipts. Since 1990, it has happened 29 times i.e. 88% of the time! (*)

(*) See Table 1.1 at https://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/budget/historical-tables/

In Schematic 3.1, the black double arrow shows that if there is a “surplus”, then cash flows out of the system in the sense that it’s available to save or spend somewhere else. Since 1990, there have been only 4 years in which there has been a Government budget surplus.

If the US spends more than what it brings in, then this triggers “deficit spending“.

Deficit spending means the Government borrows money to make up the amount that has been overspent.

It does this by selling Government securities (i.e. bonds) to anyone (mostly) who wants to buy them (which turns out to be the whole world).

You can’t borrow money for free, so there are interest payments the Government must make each year (which become part of the outlays).

What laws govern the US Federal Budget Process? Read on.

Key References and Laws

In this section we’ll review

- useful references that you can refer to for further study.

- the key laws that established and govern the current US Federal Budget Process.

Useful References

The three main Government documents I have extensively used are

- CRS: Introduction to the Federal Budget Process R46240,

- GAO: A Glossary of Terms Used in the Federal Budget Process 05734SP

- OMB: Circular No. A-11 Preparation, Submission, and Execution of the Budget

Other excellent resources:

- CRS: Congressional Research Service

- CBO: Congressional Budget Office

- OMB: Office of Management and Budget

- GAO: Government Accountability Office

- Govinfo.gov Budget Information

- PGPF: Peter G Peterson Foundation

- CBPP: Center on Budget and Policy Priorities

- CRFB: Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget

Key Laws Governing the US Federal Budget Process

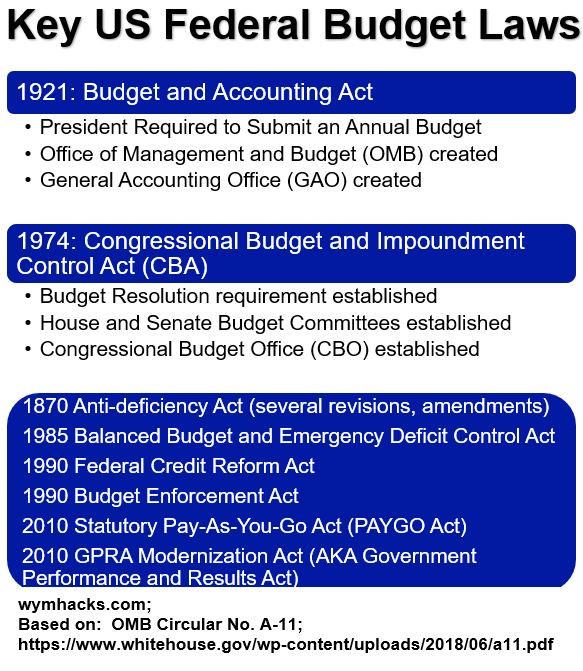

Schematic 4.1 lists the key laws driving the US Federal Budget Process. We’ll focus on the big two: The 1921 Budget and Accounting Act and the 1974 Congressional Budget and Impoundment Control Act (we’ll refer to this as the CBA).

Schematic 4.1 – Key US Federal Budget Laws

The Budget and Accounting Act of 1921

The Budget and Accounting Act of 1921

- requires the President to Submit an Annual Budget.

- created the Office of Management and Budget (OMB).

- created the US Government Accountability Office (GAO).

The GAO, “…provides Congress, the heads of executive agencies, and the public with timely, fact-based, non-partisan information that can be used to improve Government and save taxpayers billions of dollars…work is done at the request of congressional committees or subcommittees or is statutorily required by public laws or committee reports, per our Congressional Protocols.”

The OMB‘s “…mission is to assist the President in meeting policy, budget, management, and regulatory objectives and to fulfill the agency’s statutory responsibilities”.

It plays a critical role in the Formulation Phase of the US Government Budget Process.

We’ll cover this in more detail later in this article but the three phases of the Government’s annual Federal Budget Process are Presidential Formulation, Congressional Enactment, and Agency Execution.

The Congressional Budget and Impoundment Control Act of 1974

The Congressional Budget Act (CBA) of 1974, established and provides the framework for the Federal Budget Process we “follow” today.

- The CBA requires a Budget Resolution to be passed each year.

- It created the CBO (Congressional Budget Office).

- It created the House and Senate Budget Committees.

Interesting history: It appears that Congress mainly enacted the CBA to limit the President’s (Nixon at the time) power of impoundment (i.e. withholding or impounding funds appropriated by Congress).

The CBO, Congressional Budget Office “… has produced independent analyses of budgetary and economic issues to support the Congressional budget process. Each year, the agency’s economists and budget analysts produce dozens of reports and hundreds of cost estimates for proposed legislation.”

Both the House and Senate Budget Committees are integral participants in the annual Federal Budget Process. They (source: Senate.gov)

- develop Budget Resolutions which are frameworks for “congressional action on spending, revenue, and debt-limit legislation”

- enforce Budget Resolutions and associated laws and ensure spending level limits are met.

- “initiate and enforce the budget reconciliation process, a piece of legislation that is written to bring about specific identified fiscal goals.”

Summary of Key References and Laws Section

The two main laws that established the US Government Federal Budget Process are:

- The Budget and Accounting Act of 1921 (created OMB and GAO and requires an annual Presidential Budget Request)

- The Congressional Budget and Impoundment Control Act of 1974 (created CBO and Budget Committees and requires a yearly Budget Resolution.

Two excellent Government documents describing the Federal Budget Process are:

Budget Collections and Accounts

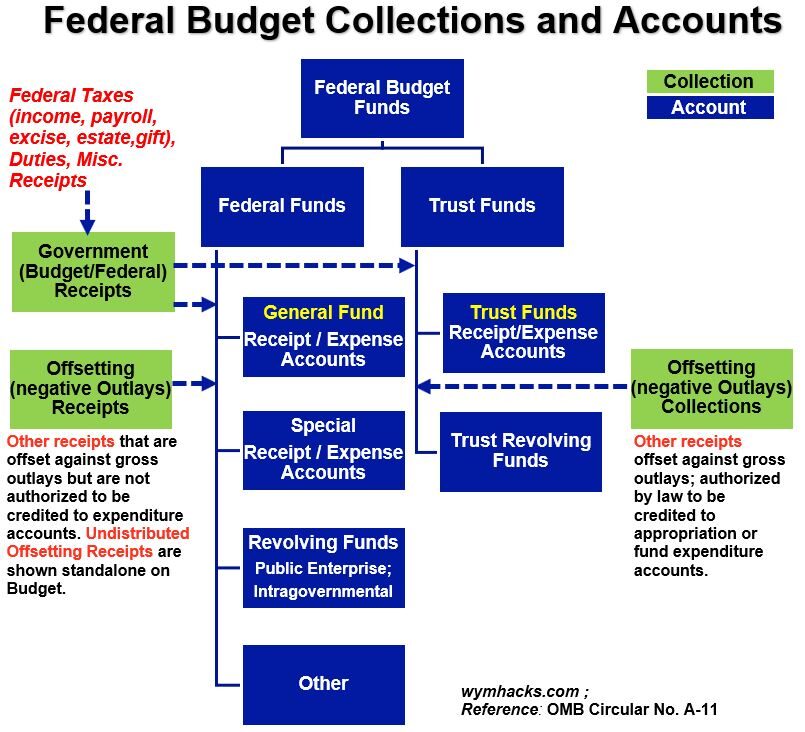

Let’s touch on some common Federal Budget terms referring to the Collection of money and money Accounts (Funds). Refer to these useful Government documents if you need more detail:

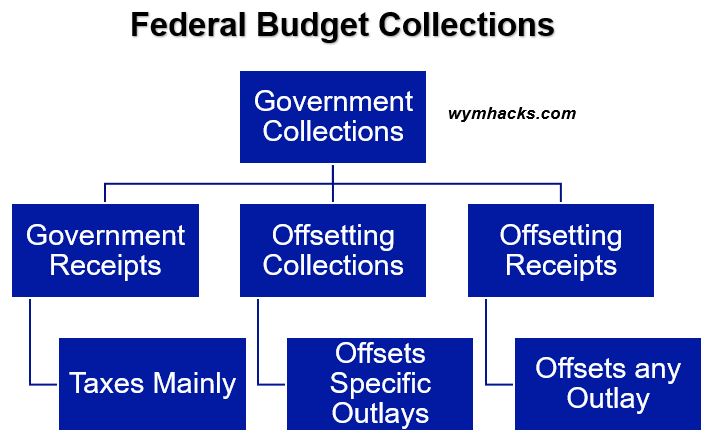

Collections refer to the money that the US Government receives from one of three sources:

- Government Receipts

- Offsetting Collections

- Offsetting Receipts

Schematic 5.1 – Federal Budget Collections

Governmental receipts result from the “exercise of the Government’s sovereign powers” i.e. power to take your money via taxes mainly.

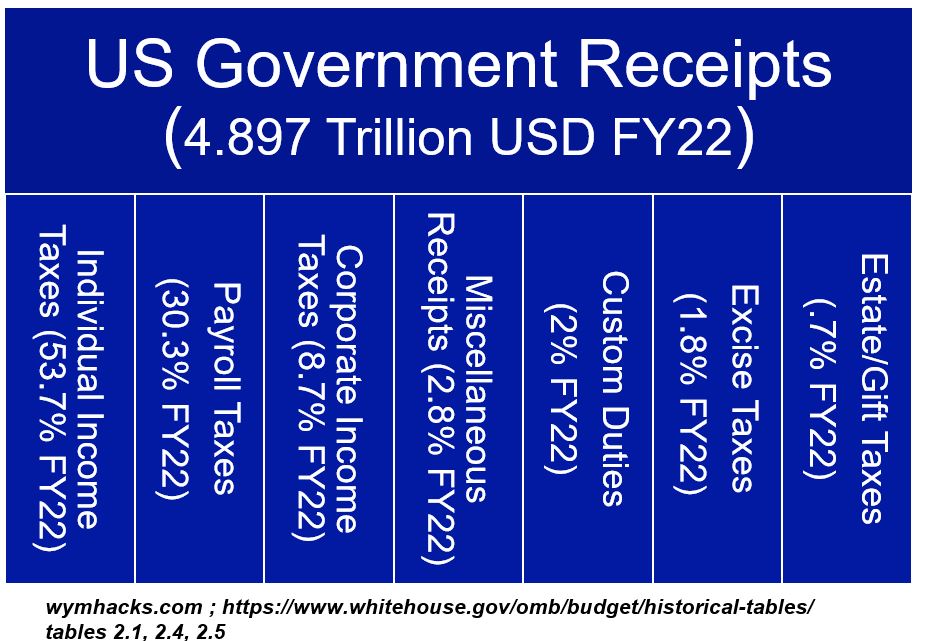

Check out Schematic 5.2 below for a breakdown of Government receipts and what they looked like for the Fiscal Year 2022 Federal Budget. They are listed below by order of magnitude.

- Individual Income Taxes (53.7% of total receipts of 4.897 Trillion USD)

- Payroll Taxes (30.3%)

- Corporate Income Taxes (8.7%)

- Miscellaneous Receipts (2.8%; e.g. regulatory fees, court fines, certain license fees, Federal Reserve earnings deposits etc. )

- Custom Duties (2%)

- Excise Taxes (1.8%)

- Estate/Gift Taxes (.7% of total receipts of 4.897 Trillion USD)

By the way, a trillion is 1000 billion or 1,000,000,000,000 (a 1 with 12 zeros behind it). It’s a really big number. (see my article on big numbers).

Schematic 5.2 – US Federal Government Receipt Breakdown for FY2022

Offsetting Receipts and Collections are additional funds collected that are recorded as negative spend (outlays). That is, they are recorded on the outlay side of the ledger and basically reduce or “offset” the outlay (like a credit would on your credit card balance). Offset examples might be benefit premiums, proceeds from Government sales, rents and royalties, interest income, postage stamp sales, etc. The term collection means the offset is dedicated to a specific program/account whereas a receipt means the offset is not credited to any specific account.

So, the Government collects and generates monies from various sources/methods and these are disbursed to various Budget Funds. Budget Funds are the receipt and expense accounts that Government agencies manage their budgets through. Budget Funds can be further broken down into two main group of funds:

- Federal Funds

- Trust Funds

Trust Funds are established by laws and are associated with programs that receive dedicated funds. The big social insurance programs like Social Security and Medicare have dedicated Trust Funds.

Federal Funds are basically everything else that is not a Trust Fund. The biggest type of Federal Fund will be the General Fund.

Schematic 5.3 shows the Collection categories (in Green) and how they related to the Budget Funds (Blue).

Schematic 5.3 Federal Budget Collections and Accounts

There are different types of Federal Funds:

- General Accounts have collections not earmarked by law for a specific purpose.

- Special Accounts have collections earmarked by law for a specific purpose. They are similar to Trust Funds.

- Revolving Funds are sources of financing that are replenished through the collection of fees or charges for goods/services provided by the Government.

Trust Funds are also broken down into two types: Trust Funds and Trust Revolving funds.

- According to Whitehouse.gov Circular No. A-11, “Revolving fund means a fund that conducts continuing cycles of business-like activity, in which the fund charges for the sale of products or services and uses the proceeds to finance its spending, usually without requirement for annual appropriations.

- …There are three types of revolving funds: Public enterprise funds, which conduct business-like operations mainly with the public, intragovernmental revolving funds, which conduct business-like operations mainly within and between Government agencies, and trust revolving funds, which conduct business-like operations mainly with the public and are designated by law as a trust fund.”

Summary of Budget Collection and Accounts Section

We now know that

- various collections (monies) enter the Federal Budget system.

- the collections mostly comprise Government Receipts (mostly Taxes) but also include Offsetting monies (Receipts or Collections) that are entered as credits or offsets against expenditures (outlays).

- modern Government Receipt totals are massive (e.g. $4.897 Trillion in FY2022) ,but we’ll see in the next section that it’s not big enough to cover expenditures.

- the collections go to either Federal or Trust Accounts.

- the General Fund (a Federal type of Fund) and Trust Funds are the two big types of Funds.

- trust Funds are dedicated funds. The big entitlement programs (like Social Security, Medicare, etc.) use Trust Funds.

Controlling Laws and Spending Categories

Appropriation and Budget Authority

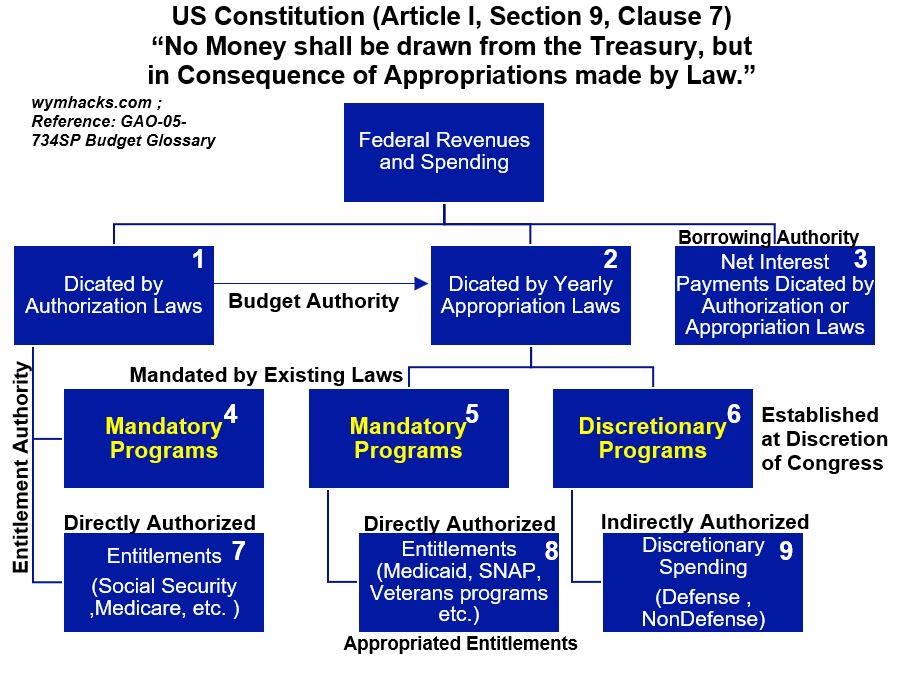

In Article 1, Section 9, Clause 7, the US Constitution states that “No Money shall be drawn from the Treasury, but in Consequence of Appropriations made by Law; and a regular Statement and Account of the Receipts and Expenditures of all public Money shall be published from time to time.”

The Legislative (law making) Branch of Government, i.e. Congress, therefore controls how money is spent ; It has the “power of the purse“.

The term “appropriation”, in the context of budgeting, generally means: “the setting aside of money for a specific purpose”. In the Federal Budget Process, when Congress enacts an Appropriation, it is giving Budget Authority to various agencies and departments to fund programs.

So, Budget Authority is essentially legal permission to finance federal programs and activities. According to OMB Circular A-11 “Budget authority…means the authority provided by law to incur financial obligations that will result in outlays.”

According to the Congressional Budget Act, there are different types of Budget Authority :

- Budget Authority (in a more specific sense): Provisions of law that make funds available for obligation and expenditure (other than borrowing authority), including the authority to obligate and expend the proceeds of offsetting receipts and collections. Note: Entitlement Authority is Budget Authority for Entitlement programs as provided in an Authorization (Authorizing) Law.

- Borrowing Authority: Authority granted to a Federal entity to borrow and obligate and expend the borrowed funds

- Contract Authority: The making of funds available for obligation but not for expenditure

- Negative Budget Authority: Offsetting receipts and collections as negative budget authority, and the reduction thereof as positive budget authority.

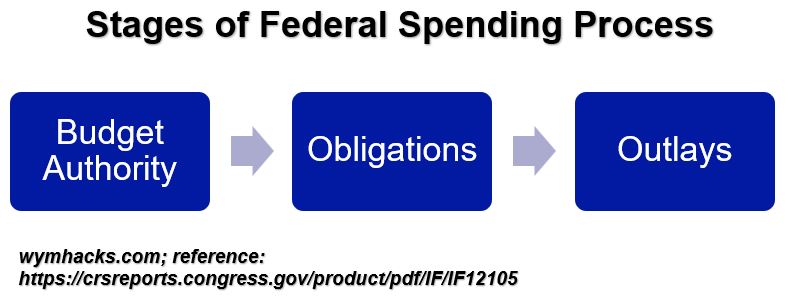

Budget Authority is typically related to Obligations and Outlays in a sequential way (See Schematic 6.1).

Schematic 6.1 – Stages of Federal Spending (Budget Authority → Obligation → Outlay)

- Budget Authority refers to the amount available to a spending agent for a specific purpose. They are the funds provided.

- Obligation refers to a spending committment. The spending agency incurs a legal binding committment (obligation).

- Outlay refers to the actual funds used (the transfer of funds to meet the agency’s obligations).

Authorizing Laws and Appropriations Laws

There are two types of laws or statues that can create and fund Federal spending programs. Almost always, Appropriations Laws require a governing Authorization Law (AKA Authorizing Law). Authorizing Laws, on the other hand, do not always require Appropriations Laws.

- Authorizing Laws (Authorization Laws or Bills) – These create, provide structure, and justify programs and (typically) provide guidelines on money that may be spent. They can sometimes contain Appropriation instructions within them. They are permanent in the sense they do not have to be updated/reviewed/created on a periodic basis.

- Appropriation Laws (Bills) – These laws typically fund an authorized program and typically are enacted on a yearly basis.

Department of Defense spending programs, for example, are appropriated each year through Appropriation laws and have associated Authorizing Laws.

On the other hand, Social Security programs are dictated by Authorizing Laws alone.

Now, let’s review three major categories of Government spending: Discretionary Spending, Mandatory Spending, and Net Interest Payments.

Spending (Expenditure) Categories

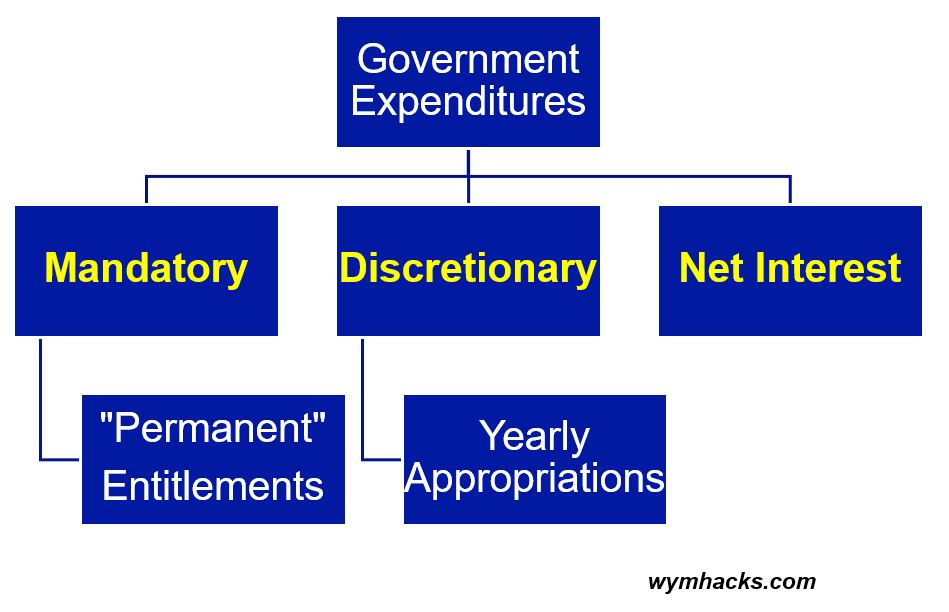

The Federal Budget defines three types of outlays (expenditures).

- Mandatory Spending – Expenses that are not Discretionary expenses. They are Mandated by permanent Authorizing Laws and don’t require annual appropriation (i.e. Appropriation Laws)… except for Appropriated Entitlements which are described later).

- Discretionary Spending – Expenses that are subject to annual (or other defined period) appropriation (i.e. require an Appropriation Law to be passed).

- Net Interest – Interest paid on Government debt, minus the portion of that interest that is received by trust funds and the net amount of other interest and investment income received by the Government. The OMB categorizes this as a Mandatory expense but the CBO does not. We’ll keep it separate and go with the CBO approach.

Schematic 6.2 – Government Expenditure Types

Discretionary Spending

The annual Federal Budget Process mostly involves Discretionary Spending which is determined at the “discretion of Congress” on a yearly (typically) basis. It involves appropriations or amounts of money that Congress allocates to federal agencies and programs for a specific fiscal year (or other defined duration).

- Discretionary expenditures are the yearly Federal department and agency outlays that are appropriated by Congress on an Annual Basis (through the Federal Budget Process).

- Typically, most of the effort around the yearly Federal Budget Process pertains to Discretionary Spending.

- The biggest portion (about 45% in FY2022) of Federal Discretionary Spending is dedicated to the Department of Defense. For this reason, Discretionary Spending is often categorized as Defense and Non-Defense (Discretionary) Spending.

- In FY2022, about 26.5% of total outlays were Discretionary! Wow, this is a minority fraction of the total spend. Hold onto this thought as you continue reading.

- According to CRS – R46240 : “The Balanced Budget and Emergency Deficit Control Act of 1985, as amended, defines Discretionary Spending as budget authority provided in annual appropriation acts and the outlays derived from that authority. Discretionary Spending encompasses appropriations not mandated by existing law and therefore made available in appropriation acts in such amounts as Congress chooses.”

Mandatory Spending

Mandatory Spending means spending controlled by laws other than appropriations acts (including spending for entitlement programs) and spending for the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program.

- Mandatory Spending , also called Direct Spending, is directly mandated by law (i.e. via Authorizing Laws) and does not require annual appropriations from Congress. Although the primary purpose of the Annual Federal Budget is to approve Discretionary appropriations, it can also change or add laws affecting Mandatory Spending (through generation of Authorizing Bills or Reconciliation Bills which we’ll address later).

- Mandatory Spending outlays continue from year to year until/unless they are changed. So, spending doesn’t have to be authorized each year and depends on the number of qualified people who receive those benefits. Social Security and Health Care Entitlement Programs (i.e. qualified people are entitled to the benefit) belong to this category.

- About 73.5% of the 2022 budget was Mandatory Spending (including Net Interest; 65.9% not including Net Interest ). Realize that this is a big chunk of the total budget process that might not necessary be part of the annual Federal Budget Process. The CBO considers Net Interest owed (on Treasury Bonds issued to cover the deficits) to be a separate spending category whereas the OMB considers it part of Mandatory Spending.

Mandatory Spending – Entitlement Programs

We’ve mentioned Entitlement Programs a few times in this section. Entitlement Programs are a kind of Mandatory Spending program.

According to Circular A-11, “Entitlement refers to a program in which the federal government is legally obligated to make payments or provide aid to any person who, or State or local government that, meets the legal criteria for eligibility. Entitlements are generally provided by an authorizing statute, and can include loan and grant programs.

Examples include benefit payments for Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid, and Unemployment Insurance, as well as grants to States for the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) and Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF). Some programs, such as Veteran’s Compensation, Medicaid, Supplemental Security Income (SSI), and Child Nutrition, are entitlements even though they are funded by appropriations acts because the authorizing statutes for the programs unconditionally obligate the United States to make payments. These are referred to as Appropriated Entitlements.”

Outlay (Expenditure) Organization

- Total Outlays

- Discretionary/Mandatory/Net Interest (the OMB tends to include Net Interest as part of Mandatory; I’d keep it separate)

- Discretionary spending can be broken down into Defense/Non-Defense.

- The CBO breaks Mandatory spending into Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid, Income Security, Federal civil and military retirement, Veterans Programs, Other Programs and Offsetting Receipts.

If we wanted a longer expense list, we could break down expenses by department or agency or by specific program. These lists will be long (100s of items). We’ll come back to departments and agencies in the following section on “Budget Participants”.

Budget Functions are another way the Government likes to break down expenses.

Budget Functions

The Government likes to display expenses by Budget Function which classify federal budgetary activities into functional categories and subcategories. Based on OMB definitions, the Budget is organized into superfunctions (total of 6), functions (total of 20), and subfunctions (total of 80) (See Appendix 1 under “Function Classifications” or Appendix 4 for more details).

For example, the “Income Security” Function , under the Super-Function “Human Resources”, has 6 Sub-Functions:

Human Resources/600 Income Security

601 General retirement and disability insurance (excluding social security)

602 Federal employee retirement and disability

603 Unemployment compensation

604 Housing assistance

605 Food and nutrition assistance

609 Other income security

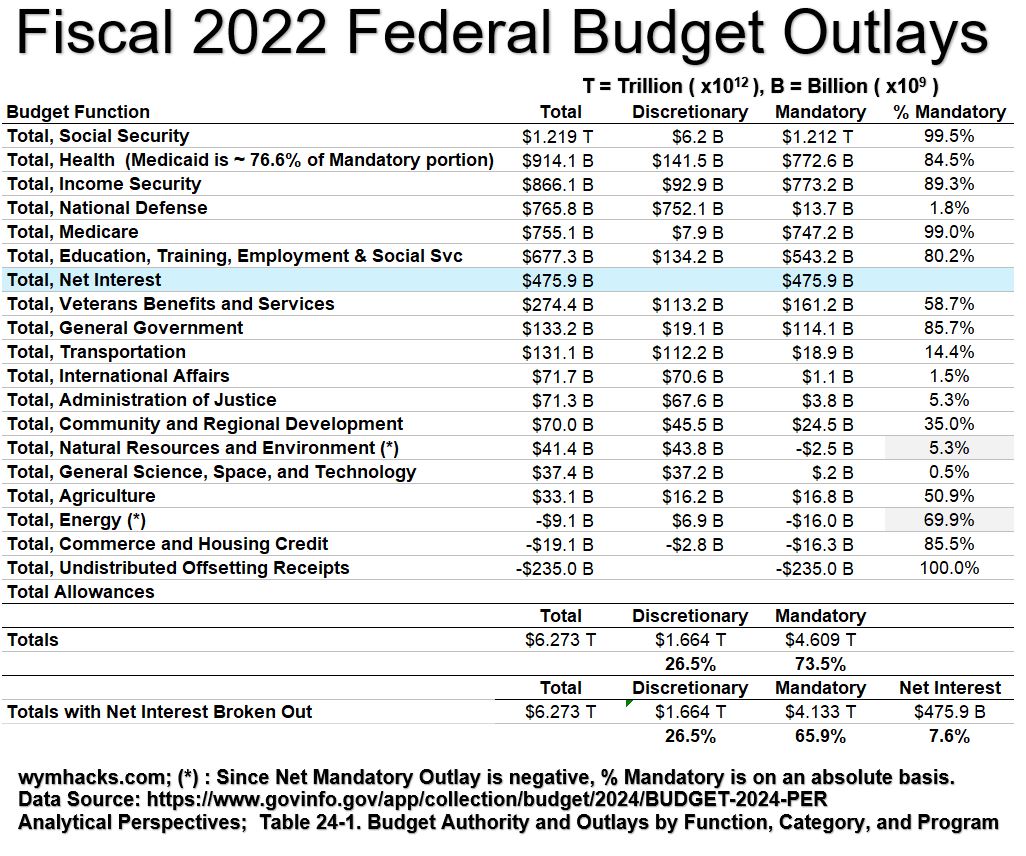

In Schematic 5.2 we showed that FY2022 Receipts totaled $4.897 Trillion. What does the other side of the ledger look like for FY2022?

Schematic 6.3 below shows FY2022 outlays (expenses) by Budget Function in Millions of dollars (total = $ 6.273 Trillion). Entitlement Programs like Social Security, Medicaid and Medicare are all huge expenses but , man, there are a lot of huge expenses. If you want to see the data table I used to construct the table below, find Table 24-1 at www.govinfo.gov 2024 budget.

Schematic 6.3 – Fiscal 2022 Federal Budget Outlays by Budget Function

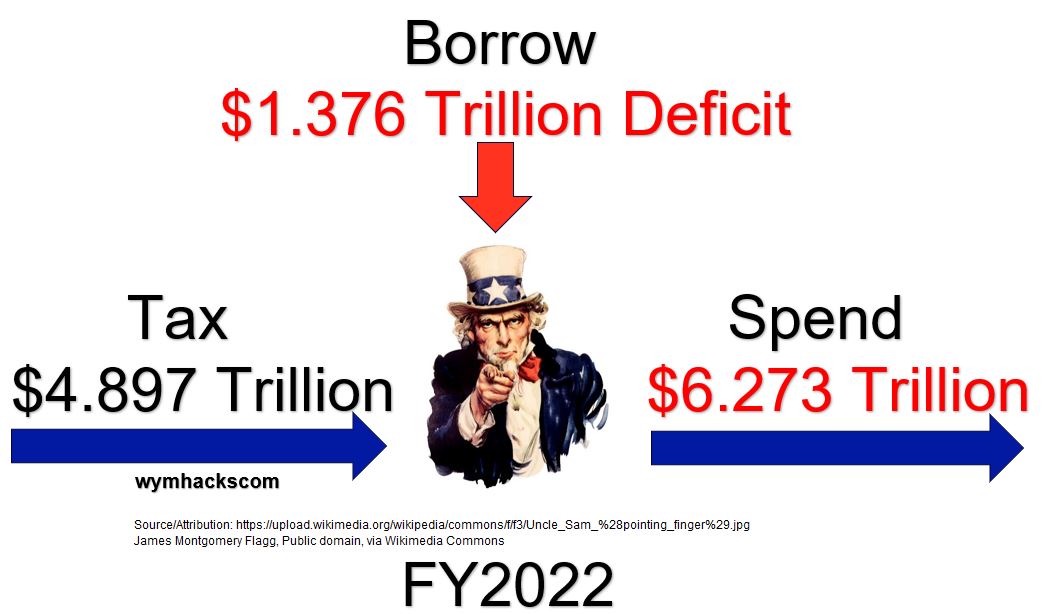

In FY2022, the Government taxed you to the tune of $4.897 Trillion and then spent all of that, and then borrowed an additional $1.376 Trillion, which it also spent (for a total of $6.273 Trillion spent).

So, we ran a $1.376 Trillion Dollar deficit in FY2022. As you look at some of these Function costs from the table above (like General Government or International Affairs etc.) are you at least curious to understand why the numbers are so huge? You should since (1) you are paying for it and (2) the government keeps on borrowing more and paying more in interest (you’re paying for this too).

Schematic 6.4 – Overall FY2022 Receipt/Outlay/Deficit

Has it been normal for the Government to run a deficit? Answer: Yes.

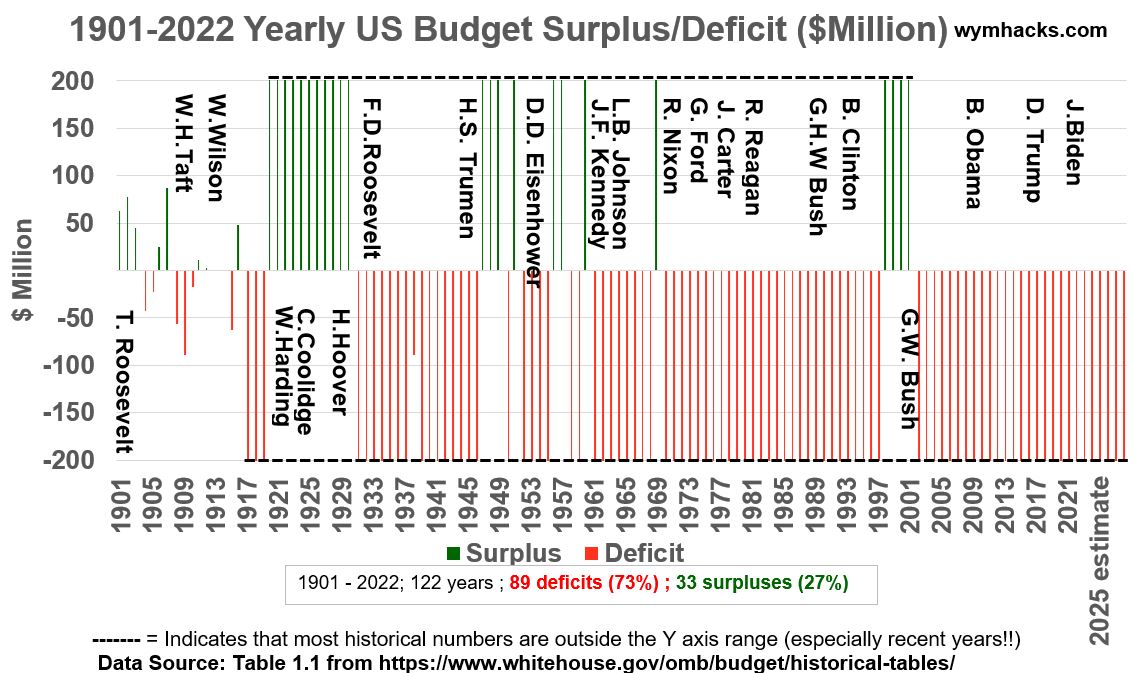

Schematic 6.5 shows the years (since 1901) in which the US ran a deficit versus a surplus. Most of the green (surplus) and red (deficit) lines extend beyond the scale of this chart, so use it just to get a qualitative sense of how often the government runs a deficit. Over 122 years, the US Government ran a deficit 89 times (73% of the time).

Schematic 6.5 – 1901 – 2022 Yearly US Budget Surplus/Deficit

Schematic 6.6 shows the yearly trend in surpluses/deficits since 1990. The Government ran deficits in 29 of the last 33 years! That’s 88% of the time. Congratulations President Clinton. Under your tenure, the Government ran a surplus for four (almost 5) straight years.

Schematic 6.6 – 1990 – 2022 Yearly US Budget Surplus/Deficit ($Trillion)

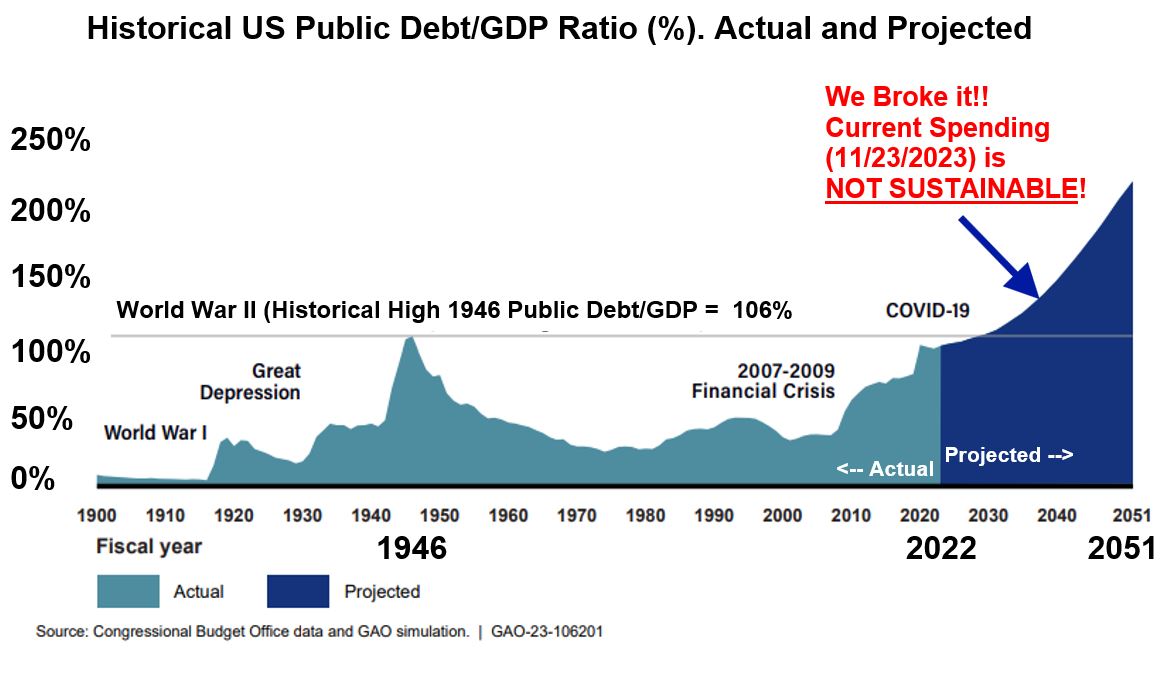

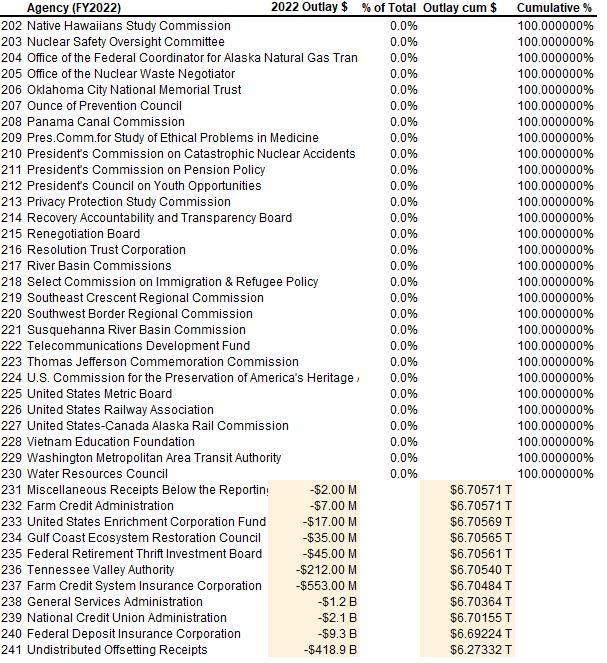

The Government Public Debt (the total cumulative debt) grows with each yearly deficit. Sometimes it’s more useful to look at relative numbers versus absolute numbers.

Schematic 6.7 shows a historical chart of US Public Debt/GDP which tells you how much the country owes relative to its economic production. During World War 2, the ratio got to about 100%. At the end of fiscal year 2022, the ratio was 97%. If nothing changes going forward, the CBO predicts the ratio will accelerate into unchartered territory. It’s difficult to identify what is too high, but everyone realizes we are entering an acceleration phase of increasing debt that will probably be very dangerous for the country.

Schematic 6.7 – Historical US Public Debt/GDP Ratio – Actual vs Projects (by CBO)

The Government knows it cannot sustain this overspending behavior shown so starkly in Schematics 6.6 and 6.7. The GAO, CBO, Social Security and Medicare Trustees, and economists on the left and right have been telling Congress and the President this for several years. This needs a dedicated article to properly address, but the main causes of unsustainable spending are:

- Demographics: The last of the 73 million Baby Boomers will reach full retirement age by 2031 (i.e. will retire into Social Security and Medicare benefits). The ratio of workers paying taxes to retirees is shrinking going from 5/1 in the 1960s to 2/1 in the next decade or so (see podcast with Brian Riedl ).

- People are living longer. When the Social Security Laws were enacted life expectancy was about 65 years (its much higher today).

- Related to the above, health costs are growing much higher than GDP growth.

- Interest on Debt grows exponentially.

- Other reasons I have heard and read about but don’t necessarily agree with are: taxes too low, social benefits are too generous, too many “pork” programs, too much spending on the military, too much foreign aid etc.

Almost all experts agree that sooner than later, the Government will need to tax more and spend less.

Relationship of Authorizing Laws, Appropriation Laws and Spending Types

Schematic 6.8 below shows the relationship between budgetary laws and types of spending. Here are the key points to remember:

- Federal Budget spending is typically described as either Discretionary or Mandatory.

- Discretionary Spending amounts are (typically) defined and approved on a yearly basis via Appropriation Laws.

- Appropriations Laws are normally associated with Authorization (Authorizing) laws which create and define the programs.

- Appropriation Laws almost always require Authorizing Laws but the opposite is not true i.e. Authorizing Laws sometimes do not require Appropriation Laws.

- Mandatory Spending programs are fully defined and controlled by Authorization (Authorizing) laws and are typically not associated with Appropriation Laws. All programs that are not Discretionary are Mandatory. They are permanent unless changed.

- The biggest Mandatory programs like Social Security are called Entitlement Programs because anyone eligible is entitled to the benefit.

- Mandatory Spending programs that are Appropriated Entitlements are an exception to the previous bullet and do require annual appropriation laws.

Schematic 6.8 – Legislative Laws and Spending Definitions

Summary

Our foundation is coming along nicely. We now know a little bit about:

- Authorizing Laws (program creation) and Appropriation (program spending) Laws.

- Mandatory (permanent by law) and Discretionary (annually appropriated) spending.

- Budget Functions which organize outlays into 20 categories.

- Historical deficits and surpluses; Debt/GDP is becoming unsustainable.

In the next section we’ll describe some of the key participants in the Federal Budget Process.

Federal Budget Process Participants

Treasury

Per treasury.gov, “The Treasury Department is the executive agency responsible for promoting economic prosperity and ensuring the financial security of the United States. The Department is responsible for a wide range of activities such as advising the President on economic and financial issues, encouraging sustainable economic growth, and fostering improved governance in financial institutions.”

During the Budget Formulation Phase of the Federal Budget Process, federal agencies receive revenue estimates and economic projections from the Department of the Treasury (Treasury), the Council of Economic Advisers (CEA), and OMB.

Council of Economic Advisers (CEA)

According to whitehouse.gov, “The Council of Economic Advisers, an agency within the Executive Office of the President, is charged with providing the President objective economic advice on the formulation of both domestic and international economic policy.” They provide input into the Formulation Phase of the annual Federal Budget Process.

OMB

As noted in a previous section, the OMB‘s “…mission is to assist the President in meeting policy, budget, management, and regulatory objectives and to fulfill the agency’s statutory responsibilities”.

It plays a critical role in the Formulation Phase of the US Government Budget Process where the Executive Office creates and submits a Budget Request (or Proposal) to Congress. It also publishes Circular A-11 , “Preparation, Submission, and Execution of the Budget”, an excellent Federal Budget Process reference.

Agencies and Departments

Agencies are Government organizations (mostly part of the Executive Branch) that fulfill the required functions of Government (i.e. carrying out the laws and policies of the United States Government).

In the Formulation Phase of the Federal Budget Process, 100s of agencies must submit their proposed budgets to the OMB.

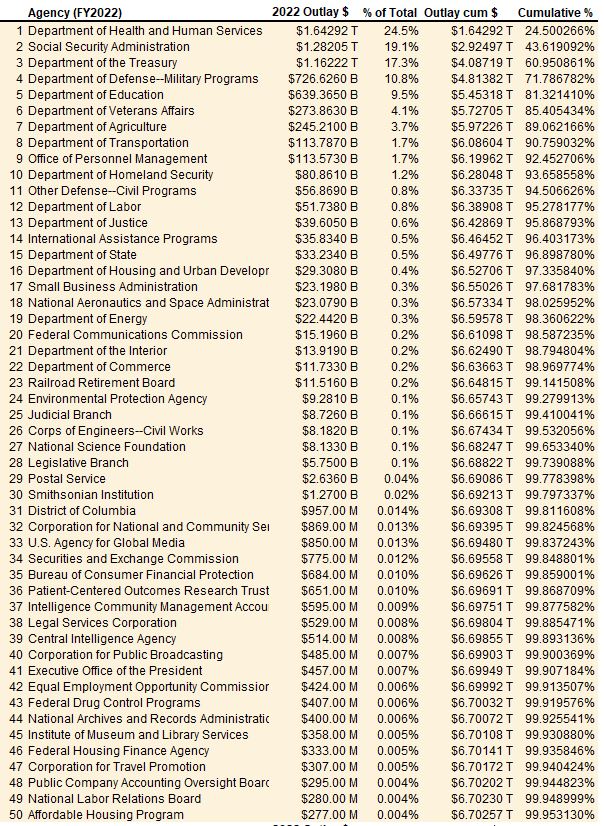

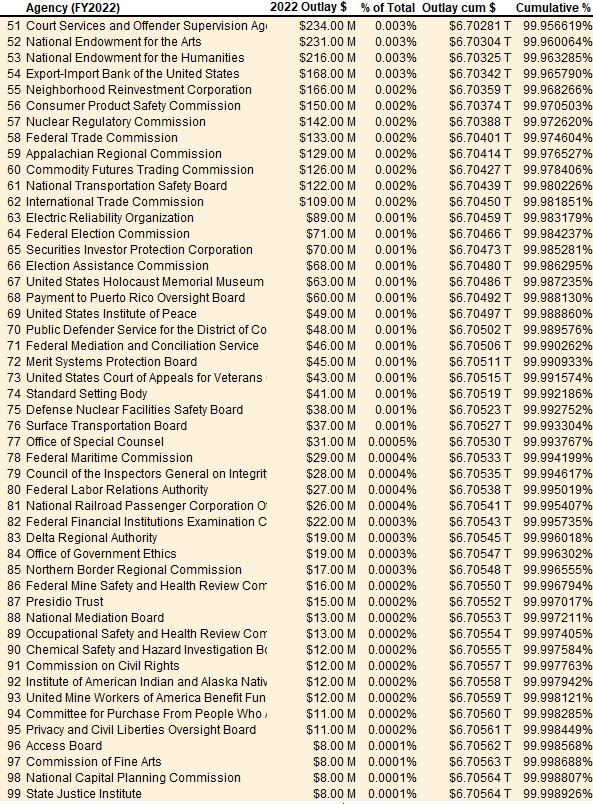

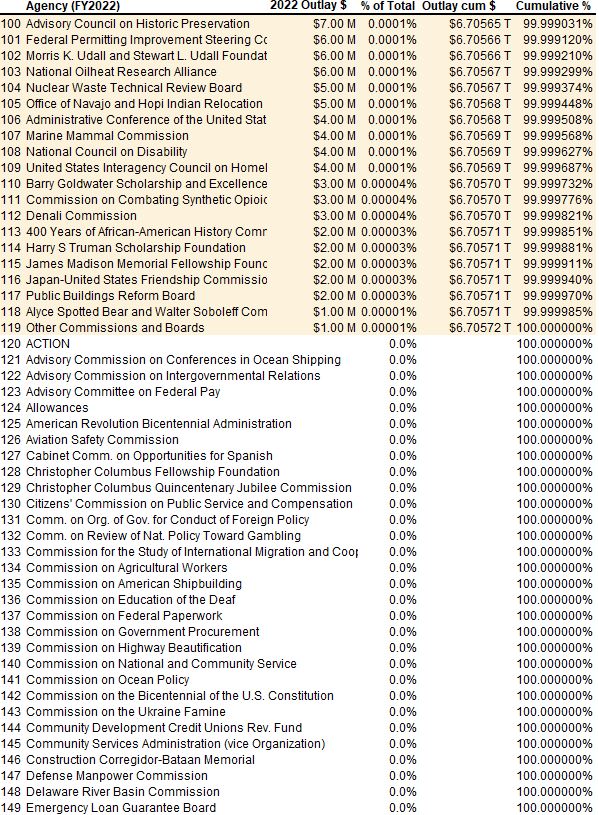

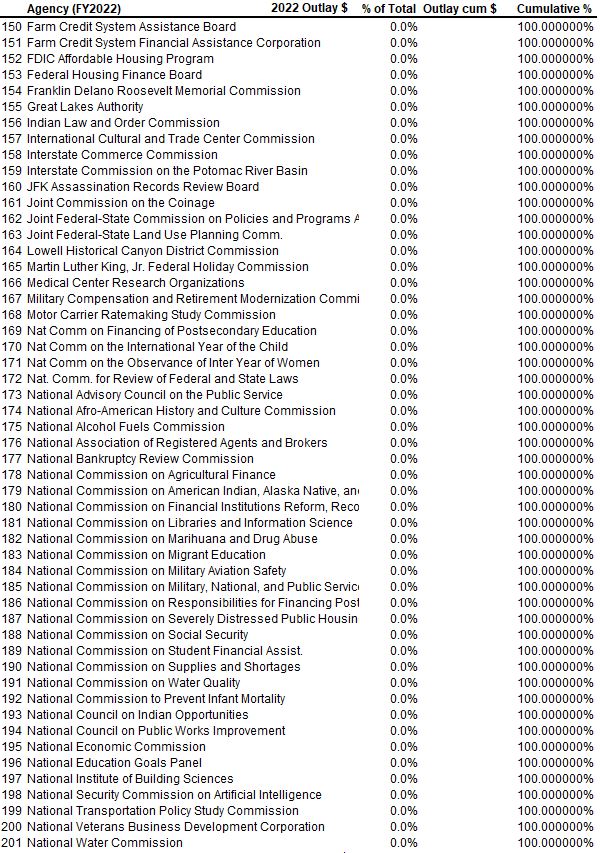

I count over 600 different federal agencies from this usa.gov agency index. Also, take a look at Appendix 3 for a listing of FY2022 budget outlays (expenditures) by agency. Notice that the top 10 agencies spend over 90% of the money. (Out of the 600 agencies, 240 were listed by the CBO in their 2022 budget summaries, with 119 being shown as having allocated budgets).

Programs

Each department/agencies might contain several “programs” operating under a dedicated allocation of money. For FY 2022, the OMB lists 563 spending programs/categories (114 offsets, 405 costs, and 43 not budgeted). Here are some of the big cost programs:

- Hospital insurance (HI): $ 339.699 Billion

- Supplementary medical insurance (SMI): $ 439.618 Billion

- Interest paid on Treasury debt securities (gross): $ 495.682 Billion

- Grants to States for Medicaid: $ 591.949 Billion

- Old-age and survivors insurance (OASI): $ 1.069768 Trillion

source: https://www.govinfo.gov/app/collection/budget/2024/BUDGET-2024-PER; Table 24-1. Budget Authority and Outlays by Function, Category, and Program

President

The head of the Executive Branch (President), the Office of Management and Budget (OMB), and numerous agencies are involved in Formulating the Presidential Budget Request. The President must also sign off (or have his/her veto over-ridden) on any Federal Budget Process produced bills (e.g. Authorizing Bills, Appropriations Bills, Reconciliation Bills).

CBO

The CBO, Congressional Budget Office “… has produced independent analyses of budgetary and economic issues to support the Congressional Budget Process. Each year, the agency’s economists and budget analysts produce dozens of reports and hundreds of cost estimates for proposed legislation.”

The CBO is an integral part of the Enactment (or Congressional) Phase of the annual Federal Budget Process. One of the first things to happen during this phase is the CBO’s issuance of their budget Baseline Estimates to Congress. They also give Congress a formal analysis of the submitted Presidential Budget Request.

GAO

As noted previously, the GAO, “…provides Congress, the heads of executive agencies, and the public with timely, fact-based, non-partisan information that can be used to improve Government and save taxpayers billions of dollars…work is done at the request of congressional committees or subcommittees or is statutorily required by public laws or committee reports, per our Congressional Protocols.”

The GAO provides data and is involved in budget related audits. It publishes an excellent document GAO 734sp, “A Glossary of Terms Used in the Federal Budget Process”.

Congress of the United States

The Constitution , particularly article I, section 9, clause 7, empowers Congress with the Power of the Purse i.e. Congress is the designated money appropriator.

In the Enactment Phase of the Federal Budget Process, Congress receives the President’s Budget Request and then creates a Concurrent Budget Resolution and Enacts spending laws for the upcoming fiscal year.

Ref4 (GAO-05-734SP ): “The United States Constitution gives Congress the power to levy taxes, to finance Government operations through appropriations, and to prescribe the conditions governing the use of those appropriations. This power is referred to as the congressional “power of the purse.”

…The power derives from various provisions of the Constitution particularly article I, section 9, clause 7, which provides that: “No money shall be drawn from the Treasury, but in Consequence of Appropriations made by Law; and a regular Statement and Account of the Receipts and Expenditures of all public Money shall be published from time to time.”

…Congress has and continues to implement its power of the purse in two ways: through the enactment of laws that raise revenue and appropriate funds, including annual appropriations acts, and through the enactment of “fiscal statutes” that control and manage federal revenue and appropriations…“

House and Senate Budget Committees

Typically these are the first committees to act during the Congressional Phase (Enactment Phase) of the Federal Budget Process. The Budget Committees are required to create and pass yearly Concurrent Budget Resolutions which set total spending limits (top line 302(a) allocation).

- Ref2 (CBPP): “The House and Senate Budget Committees draft and enforce the congressional budget resolution. Once the Budget Committees pass their budget resolutions, the resolutions go to the House and Senate floors, where they can be amended. The budget resolution for the year is adopted when the House and Senate pass the identical measure, either after negotiating a conference agreement or after one chamber passes the resolution adopted by the other.” The final product is called the Concurrent Budget Resolution.

- The House and Senate Budget Committees can also request and approve Reconciliation Bills which mainly authorize changes in Mandatory Spending and taxes.

House and Senate Authorizing Committees

An Authorizing Committee is a standing congressional committee (see Committee definition in Appendix 1 or detailed listing of committees in Appendix 2) that also serves as an Authorizing Committee.

Authorizing Committees have subject matter expertise over certain agency programs and have the role of authorizing these programs; meaning giving people authority and providing the structure and rules under which those programs operate.

Both Mandatory and Discretionary Spending bills are typically authorized.

- For example, the House and Senate Armed Services Committees would be Authorizing Committees for certain Department of Defense programs.

- Authorizing Committee definition – Ref4 (GAO-05-734SP ): “A standing committee of the House or Senate with legislative jurisdiction over the establishment, continuation, and operations of federal programs or agencies. The jurisdiction of such committees extends, in addition to program legislation, to authorization of appropriations legislation. “

- Authorizing Committee definition – Ref1: (CRS – R46240) : “Legislative committees—such as the House Committee on Armed Services and the Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation—are responsible for authorizing legislation related to the agencies and programs under their jurisdiction. Most standing committees have authorizing responsibilities.

House and Senate Appropriations Committees

These congressional committees play a key role in the Enactment Phase of the annual Federal Budget Process. The Senate and the House each have 1 Appropriations Committee and 12 Appropriations Subcommittees (a total of 26 congressional committees not including the joint Conference committees comprised of house and senate members). In the Federal Budget Process, these Committees write legislation that allocates funds to various Government agencies.

House and Senate Appropriations Sub-Committees

The House and Senate each have 12 (24 total) Appropriations Subcommittees which divvy up the work of allocating spending limits to each of their 12 appropriations spending categories. These allocations are sometimes called 302(b) allocations.

Conference Committees

Conference Committees are ad-hoc committees which comprise members of Budget, Authorizing, or Appropriations Committees. They are used to reconcile House and Senate versions of various budget bills.

Summary of Participants Section

During the Formulation, Enactment, and Execution phases of the annual Federal Budget Process, the key players listed above are expected to interact, share, negotiate, cajole and ultimately come up with a budget for the upcoming fiscal year. You can imagine how complicated this might get and the pressures involved to do this on a yearly basis.

Moving along, we need to do a little mini civics lesson next so you can appreciate the legislative process required to pass budget laws (or any law for that matter).

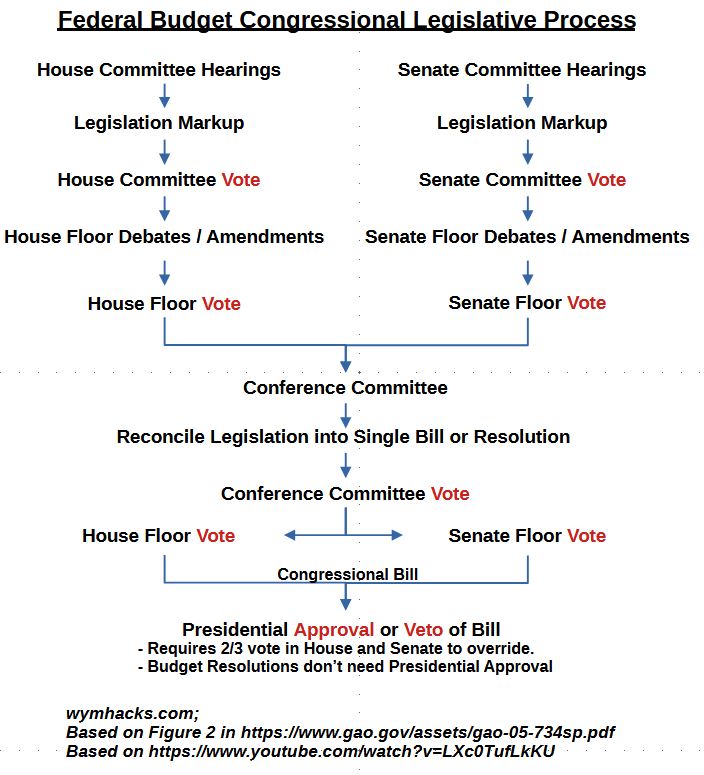

Federal Budget: Legislative Process

Schematic 8.1 below should give you an appreciation for the many steps that have to happen for budget related reports and bills (laws) to be created and approved. Except for some procedural details, this process really applies to any federal legislation.

The chart format might suggest to you that the House and Senate are moving through parallel activities that are independent of each other. In reality there might be legislative drafts that originate in one house that are then shared and become the starting point for legislative drafts in the other house.

Consider the Origination Clause in the US Constitution Article I, Section 7, Clause 1: “All Bills for raising Revenue shall originate in the House of Representatives; but the Senate may propose or concur with Amendments as on other Bills.” So, revenue altering laws (e.g. laws that impact tax rates) , for example, are originated in the House with subsequent Senate involvement to finalize the bill.

Let’s describe the legislative process at a high level. I think Phil Candreva succinctly describes the legislative process in his video, An Introduction to the Federal Budget Process, at time 8:33/16:40. You should have a listen to it.

Legislative Process

Schematic 8.1 – Federal Budget Congressional Legislative Process

As we’ve noted, Congress has the “power of the purse” and must issue budgetary laws that control the Federal Budget. Some are issued as required and become permanent until changed (Authorizing Laws) and some are updated/created on a periodic basis (yearly typically…Appropriation Laws).

Every year, after (or shortly before , more accurately) Congress receives the Presidential Budget Request (a product of the Formulation Phase of the Budget Process), it begins the legislative process shown in Schematic 8.1. In the sequence described below, we assume success and agreement has been reach before any subsequent step is described. Obviously there will be separate “recirculating” procedures when agreements are not reached.

- House and Senate Committees hold hearings which are meetings and discussions with all relevant experts

- Legislation is marked up and voted on within the committees.

- The Chambers (House or Senate) then discuss, debate and amend as needed.

- The Chambers vote on it.

- Ad hoc Conference Committees are then assembled from the House and Senate Committee membership to reconcile the House and Senate versions into a single law or bill (or resolution which is not a law).

- The Conference Committee votes to approve.

- The approved reconciled legislation or resolution is brought back to the House and Senate for another vote.

- Finally, a law (or bill) is enacted once approved by the President.

There are some special voting rules that apply to some of the budget related legislation, but we’ll get to that later when we discuss Budget Resolutions and Budget Reconciliation Bills.

Is the Legislative Process a Truly Parallel Process?

The schematic above suggests that the House and Senate activities are doing similar things at the same time. This is not true in practice. In general, the House is the first chamber that will introduce legislature and go through the process, especially if the bill or law is related to changing revenue (see Constitution wording about this Origination Clause). But in the end, both chambers have to work together , along with the President, to pass laws.

It’s Convoluted and Complicated

Think about how complicated this process can get. For example, there are 2 Appropriations Committees but an additional 12 Appropriations Subcommittees (in House and Senate) that have to negotiate , compromise, and come to agreement. Also, any disagreement or impasse along the way requires moving back up the process flow for a do-over. This process looks , on paper, like it could be really hairy. In reality, it is exactly that.

General Overview of the Federal Budget Process Phases

As needed, you can reference two excellent Government documents that describe the phases of the US Federal Budget Process: OMB-A11 and GAO-734SP .

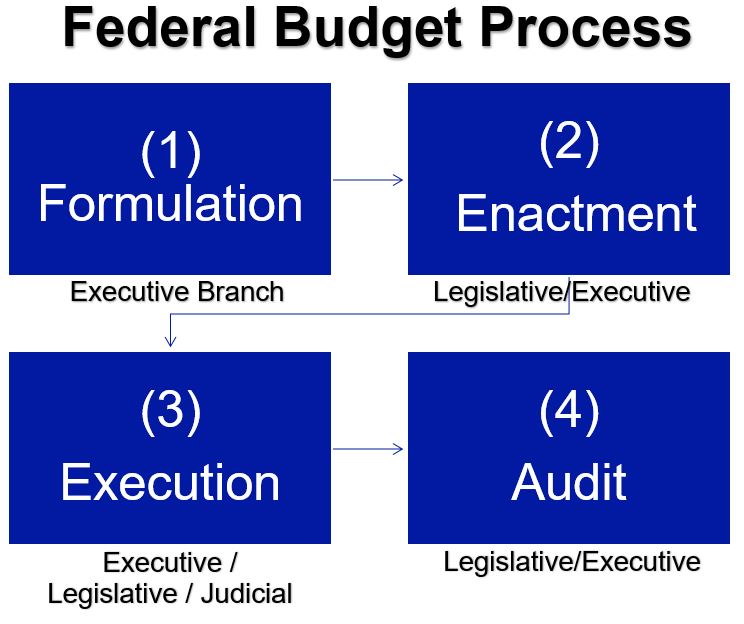

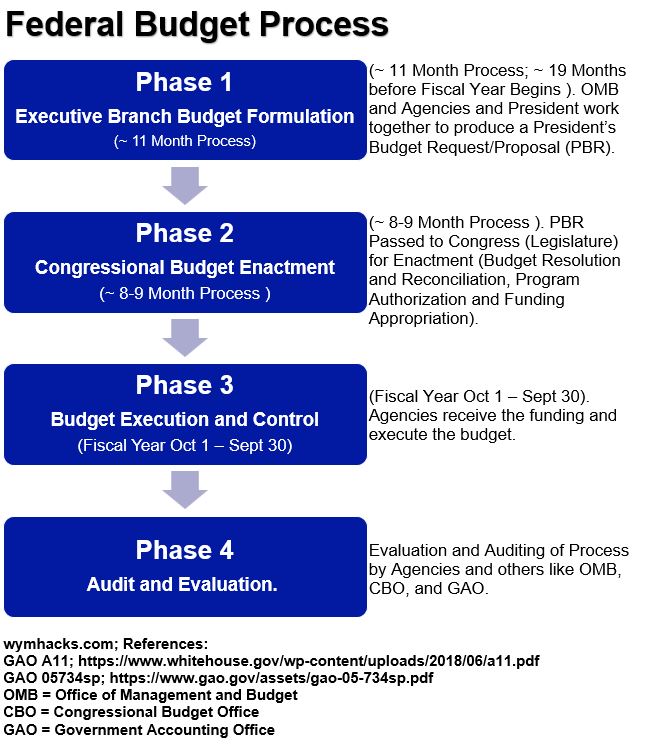

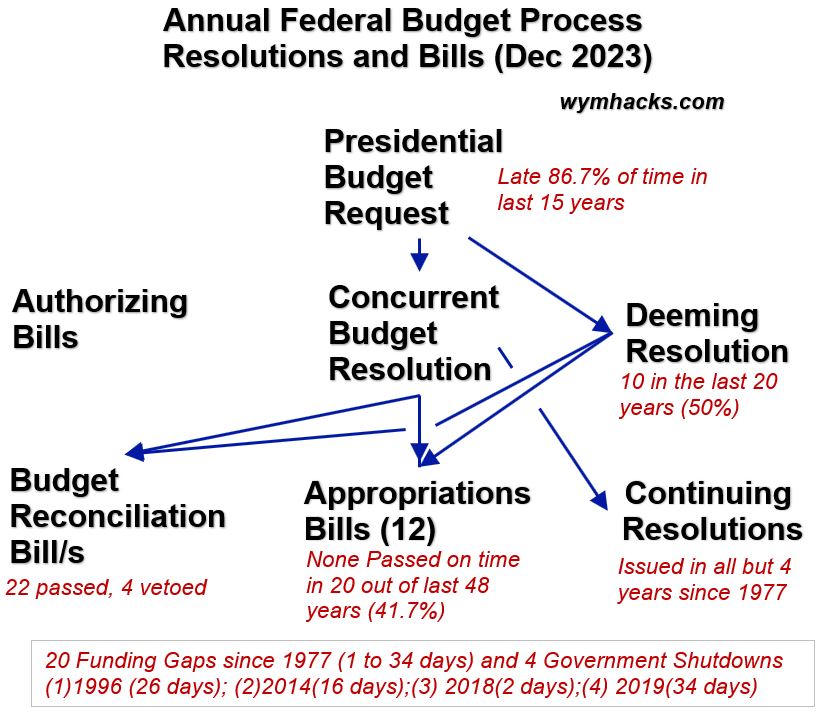

The four phases of the US Federal Budget Process are (See Schematic 9.1):

- Budget Formulation by the Executive Branch or Office (President)

- Budget Enactment by the Legislative Branch (Congress)

- Budget Execution (agencies spend the money)

- Budget Audit and Evaluation

We are going to focus on the first two phases, Executive Office Budget Formulation and Congressional Budget Enactment.

Schematic 9.1 – High Level Federal Budget Process Flow

The overriding purpose of the Federal Budget Process is to have an approved budget in place before the start of the Fiscal Year for that budget.

The US Fiscal Year for a budget starts on October 1st and ends on September 30th of the following calendar year. The year we use to describe a Fiscal Year is the year in which the Budget period expires. So, for example, the 2024 Fiscal Year starts on October 1st, 2023 and ends on September 30, 2024.

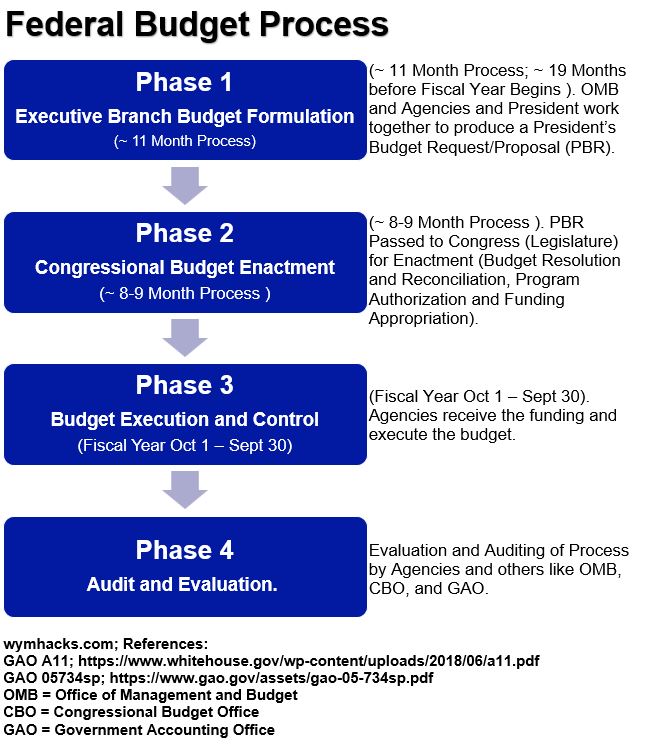

Phase 1 (Formulation)

The purpose of the Budget Formulation phase is for the Executive Office to submit a Presidential Budget Request (PBR) to Congress by early February of the following year. Note that:

- The PBR is not enforceable by law (not a statute).

- The PBR is simply a request to Congress that shows what the agencies think they need and also signals any of the President’s priorities for the next budget.

- It also might include proposals for changing budget related laws, like increasing or decreasing tax rates (as part of an Authorizing Law or Reconciliation Bill…more on this later).

- The PBR is a massive set of documentation. You can see the latest version in this OMB web site.

Formulation takes about 1 year, starting in the Spring (let’s say March) and ending when the PBR is submitted to Congress in early February of the following calendar year. In the Spring, Government agencies and departments , with guidance from the OMB, develop their detailed proposed budgets.

These are eventually submitted to the OMB for review, where a back and forth process occurs to finalize the budgets. This is not a trivial task and involves hundreds of agencies and departments.

Phase 2 (Enactment)

The Enactment Phase occurs around the time the Presidential Budget Request, PBR, is submitted to Congress. Congress has the power of the purse, and so they have discretion to accept or reject any parts of the PBR.

This phase, taking around 8 to 9 months, involves Congress taking the PBR and using it as a starting point to develop a unified (between House and Senate) Concurrent Budget Resolution.

The Concurrent Budget Resolution is a comprehensive revenue and spending plan which allows the enactment of 12 Appropriation Laws (Bills). These laws generally provide “legal authority for federal agencies to incur obligations and to make payments out of the Treasury for specified purposes.”

Each Appropriation Bill is developed by one of the 12 Appropriations Subcommittees (see Appendix 2 for a listing). For example, The “Commerce, Justice, Science, and Related Agencies” Appropriations Bill includes funding for the Department of Commerce, the Department of Justice, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), National Science Foundation (NSF) etc.

In addition to Appropriation Bills, the Enactment phase can also produce Authorization (Authorizing) Laws, Reconciliation Laws (revised Authorization Laws) and Continuing Resolutions (temporary Appropriation Laws). We’ll come back to these later.

Phase 3 (Execution)

The Execution Phase is the spending phase. Spending programs might cover one fiscal year (many of the Discretionary Spending programs), multiple years, or no years (many Entitlement Programs don’t have defined periods and go on indefinitely until the Authorizing Laws are changed.)

Remember that each Fiscal Year starts on October 1st and ends on September 30 of the following year (and the attributed year is always the latter year).

Phase 4 (Audit/Evaluation)

There are continuous budget auditing and evaluations going one, conducted by the Executive and Legislative Branch OMB and CBO (respectively) as well as the agencies themselves.

The Inspector General Act of 1978, the Chief Financial Officers Act of 1990, the Government Management Reform Act of 1994, the Federal Financial Management Improvement Act of 1996 , the Government Performance and Results Act (GPRA), the Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, and the Impoundment Control Act of 1974 all provide guidance and set requirements for auditing and evaluating spending programs.

Schematic 9.2 below adds a little more detail to Schematic 9.1.

Schematic 9.2 – Federal Budget Process Phases

Summary of Yearly Budget Process

The annual Federal Budget Process proceeds as follows:

- The Executive Office Formulates a Budget Request (Proposal) and submits it to Congress.

- Congress Passes a Concurrent Budget Resolution and Enacts 12 Appropriations Laws which set Discretionary Spending levels.

- During the Enactment period, Congress can also pass Authorization (Authorizing) Laws, Reconciliation Laws, and Continuing Resolution Laws which we will address in a later section.

- The various agencies then Execute the budget (i.e. take obligations and pay cash) during the Fiscal Year (October 1 – September 30).

- Auditing and Evaluations occur throughout the process.

So we now know that it takes about 1.5 years to prepare a Federal Budget. But, how many budget cycles are going on at any given time? Let’s explore this a little in the next section.

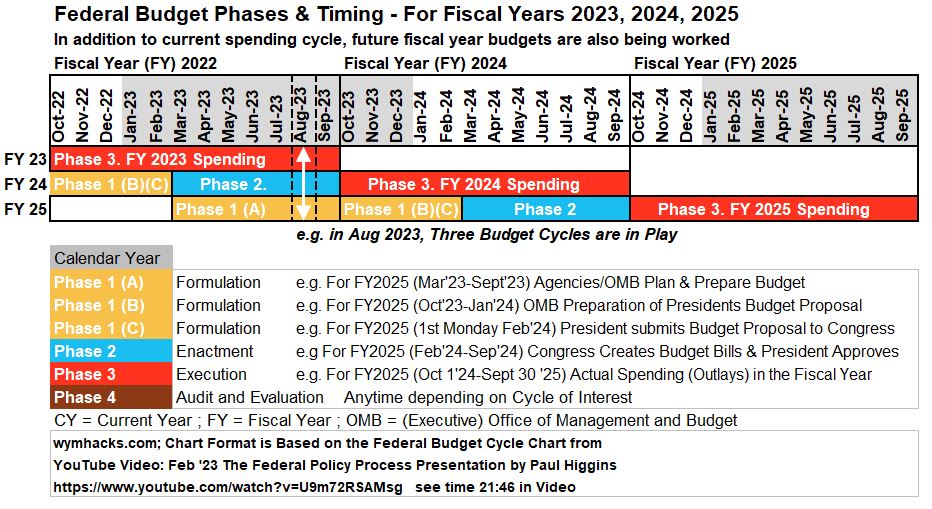

Federal Budget Process Cycle/Timing

At this point, you should have the definite sense that preparing a single Federal Budget takes quite a bit of time and effort. But, at any given time, there might be as many as three different budget cycles, at different stages, being concurrently managed by the US Government.

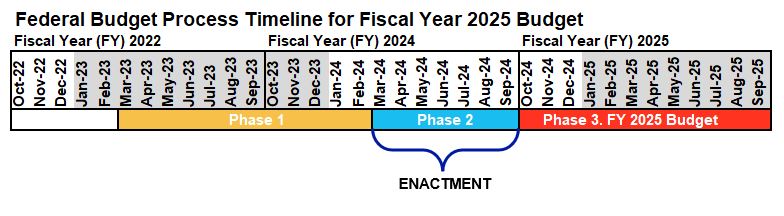

Schematic 10.1 overlays Fiscal Year (FY) 2023, FY 2024 and FY 2025 budget activities.

The table header separates the months by Fiscal year (October – September) with the Calendar years shaded in grey. The three rows below the header map the budget phases for that year (FY23 or FY24 or FY25) against the months in the header. The phases are shown in different colors (we don’t show the audit phase to keep the chart less cluttered)

Schematic 10.1 – Federal Budget Phases and Timing for FY23,24,25

Focus on the 3rd row in the schematic above. This shows the full budget cycle for Fiscal Year 2025 (FY 25). For the Fiscal Year 2025 Budget, Phase 1 begins in March 2023 and ends in early Feb 2024 when the President presents the 2025 Presidential Budget Request (Proposal) to Congress.

Then between Feb. and Sept. 2024, Congress Enacts budgetary legislation in time for the beginning of the FY 2025 Budget (which begins on October 1 2024 and ends in September 30 2025).

Notice that there are three budget cycles in play. Assume that we are in August 2023 (see the white vertical double arrow in Schematic 10.1). At this time the US Government is Executing the FY 2023 Budget, Enacting the FY 2024 Budget , and Formulating the FY 2025 budget!

Summary of Federal Budget Process Cycle Timing Section

The US Government has the heady task of managing not only one but three Federal Budgets at any given time. For example in August 2023 the Government was

- Executing the FY 2023 Budget,

- Enacting the FY 2024 Budget , and

- Formulating the FY 2025 budget!

Let’s now dig deeper into the Formulation Phase of the Federal Budget Process.

Federal Budget Process – Phase 1 – Formulation

This section provides a little more detail on the Formulation phase of the Federal Budget Process.

Below is a Formulation Phase timetable, excerpted from Ref 1: GAO 5734sp Appendix I and Ref 2:OMB Circular A-11 Section 10. Excerpts are in quotations.

Ref 1:”Spring–Summer: OMB Establishes Policy for the Next Budget Request”

- Ref 2: “OMB issues spring planning guidance to Executive Branch agencies for the upcoming budget” (providing policy guidance for Budget Request).

- Ref 2: “OMB and the Executive Branch agencies discuss budget issues and options.”

- Ref 2: “OMB issues Circular No. A–11 (detailed instructions) to all federal agencies.”

Ref1:”September–October: Agencies Submit Initial Budget Request Materials”

Ref2: Agencies make and send in budget submissions to the OMB.

Ref 1: “October-December: OMB Performs Review and Makes Passback Decisions”

- Ref2: “OMB conducts its fall review. It analyzes agency budget proposals in light of Presidential priorities, program performance, and budget constraints. They raise issues and present options to the Director and other OMB policy officials for their decisions.”

- Ref2: Late November: “OMB briefs the President and senior advisors on proposed budget policies. The OMB Director recommends a complete set of budget proposals to the President after OMB has reviewed all agency requests and considered overall budget policies.”

- Ref2: Late November: “Passback. OMB usually informs all Executive Branch agencies at the same time about the decisions on their budget requests.”

- Ref2: December: “Executive Branch agencies may appeal to OMB”. Appeals are resolved by the OMB and agency or ,if needed, by the President.”

- Ref2: January: “Agencies prepare and OMB reviews congressional budget justification materials” (for congressional subcommittees).

Ref1:”By the First Monday in February: President Submits Budget Request”

- Ref2: February: “The President transmits the budget to the Congress ” by First Monday in February.

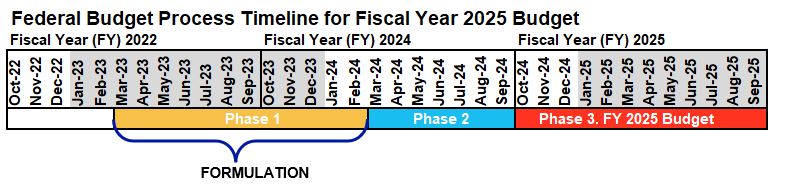

Schematic 11.1 shows the Formulation phase on a FY2025 Budget Calendar. It takes roughly 11 months to complete.

Schematic 11.1 – Calendar showing Formulation Phase for FY 2025 Budget

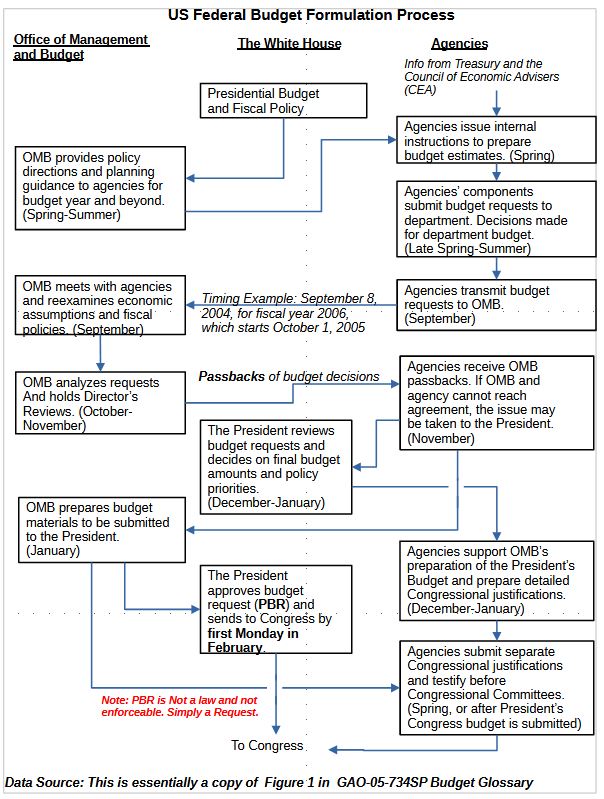

See the Formulation Phase steps in Schematic 11.2 (which I essentially copied from GAO-05-734sp figure 1).

Schematic 11.2 – US Federal Budget Formulation Process – Figure 1 – GAO05734sp

Presidential Budget Request Purpose

The PBR serves to:

- provide detailed budgetary data (for the upcoming Fiscal Year but also the following 9 years) including how much tax to collect and how much of a deficit the Government will run.

- define the President’s relative program priorities and how much money should be spent on them.

- includes any recommended Mandatory Spending law (e.g. Social Security) or revenue law (e.g. tax law) changes.

Presidential Budget Request Content

The PBR is a massive collection of current, historical , and estimated future budget amounts. You can review the documents in detail at Govinfo.gov. The PBR

- includes budget data for the upcoming fiscal year as well as the current year, past years, and estimated future years.

- contains requested appropriation changes or new appropriations for the current or upcoming fiscal years (respectively).

- estimates receipts by type and outlays by Agency and Account.

- estimates outlays by major Government Budget Functions.

- includes actual and estimates of surpluses and deficits.

- includes several other documents addressing economics, revenue, collections, taxes, debt, trust funds etc.

Check out Appendix 4 for a description of Government Budget Functions and Appendix 3 for information on Government agencies.

Presidential Budget Request – Impact on Enactment Phase

The Presidential Budget Request (PBR) does not carry any legal authority but it is required to be submitted to Congress by the first Monday in February of each year.

Congress can use the PBR as a starting point for the Enactment phase of the annual Federal Budget Process, but it is not obligated to duplicate it by any means. Often, significant changes are made by Congress. The lack of statutory authority of the PBR does not make it unimportant , as it can be used to communicate the President’s priorities to Congress and the public.

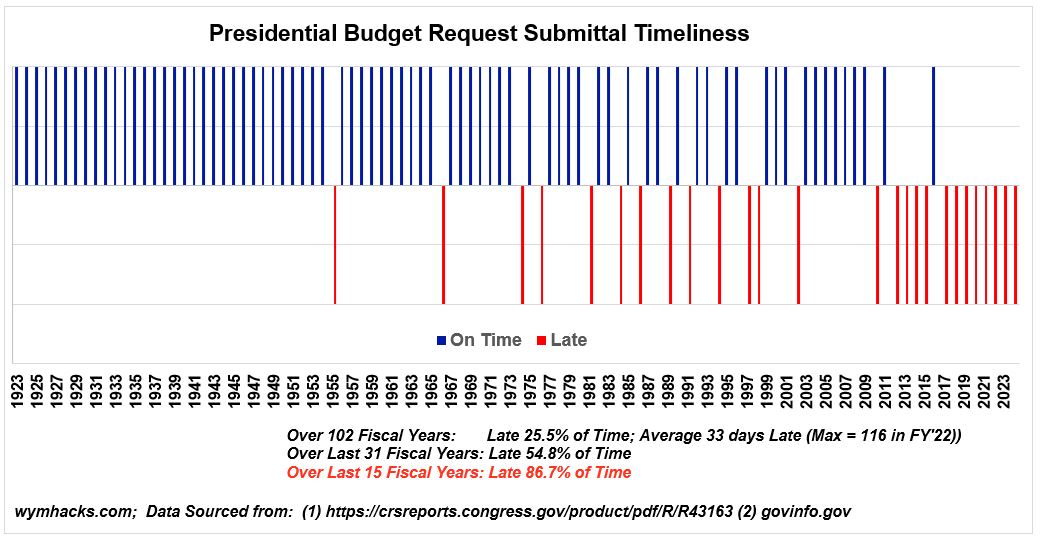

Presidential Budget Request – Timeliness

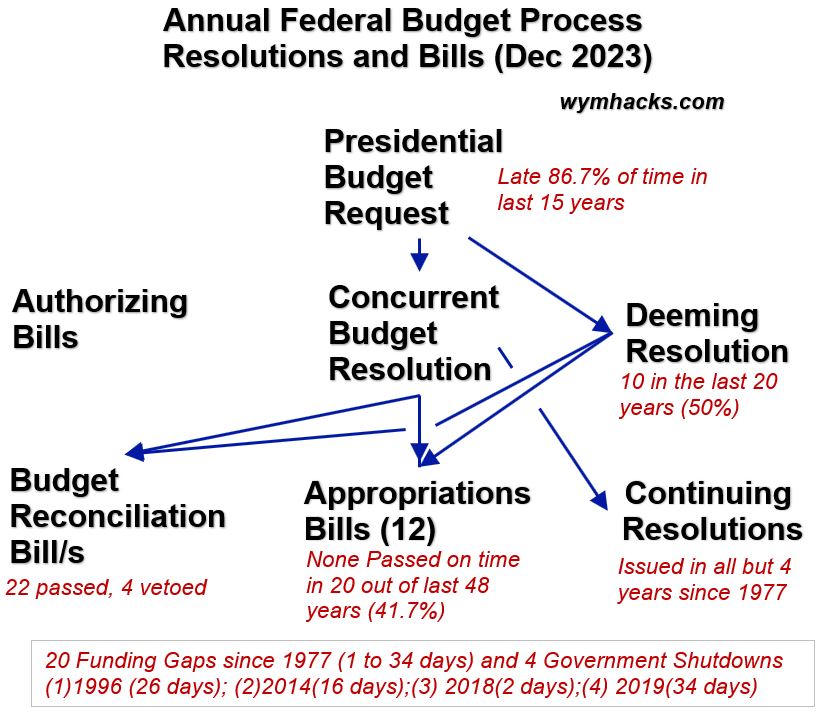

Let’s end this section with a little audit. How often do you think the President and his OMB have made an on-time submittal of their PBR to Congress? Using CRS report R43163 and Govinfo.gov here are the numbers:

- All though there is a statutory requirement to get the Presidential Budget Request (PBR) submitted on time (since 1990 the deadline has been the 1st Monday in February), there are no penalties associated with non-compliance.

- In the last 102 fiscal years, the PBR was submitted late 25.5% of the time by an average of 33 days.

- In the last 31 fiscal years, the PBR was submitted late 54.8% of the time (bad)!

- In the last 15 fiscal years, the PBR was submitted late 86.7% of the time (really bad)!

Schematic 11.3 – Presidential Budget Request Timeliness (FY1923 – 2023)

So, long term, the Executive Office has done an average job of submitting the PBR on time; and short term, it’s done much less than average. An untimely PBR submittal threatens the timely completion of the following steps that happen once the PBR is submitted to Congress.

What happens after the President submits the PBR to Congress? Read on!

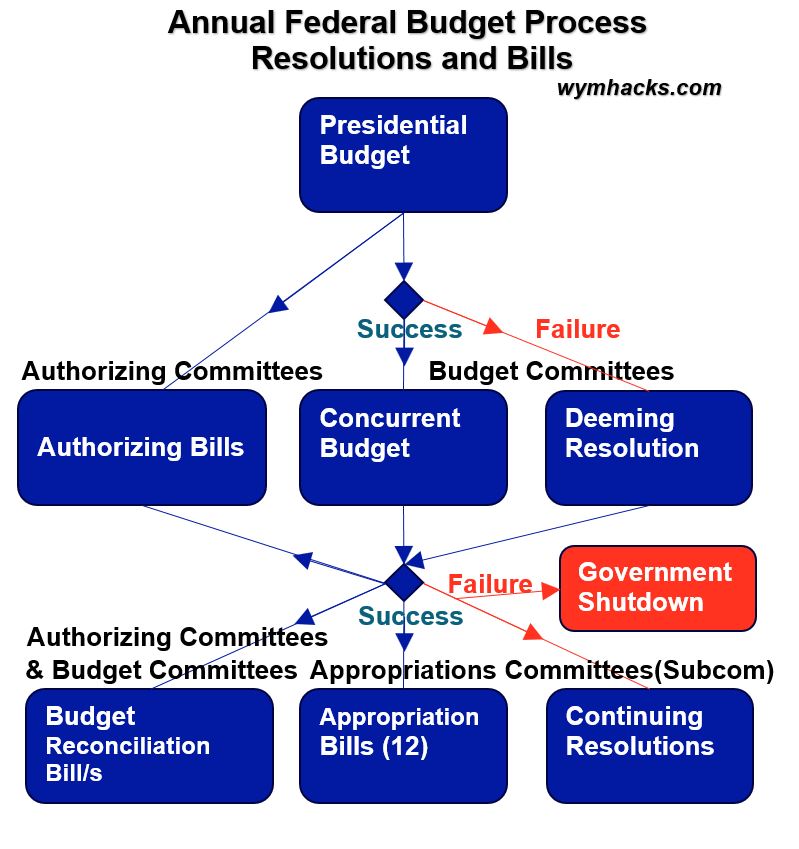

Budget Process – Phase 2 – Enactment

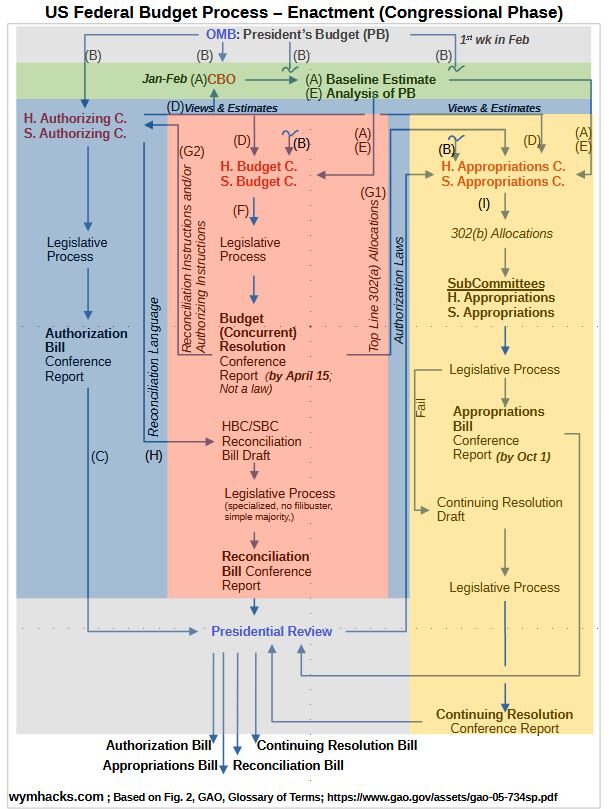

The Enactment Phase of the Federal Budget Process is sometimes called the Congressional Phase. It essentially begins when the President/OMB submit the Presidential Budget Request (PBR) to Congress. Since Congress has the constitutional “power of the purse”, it has final authority over what the budget and associated laws looks like.

We’ve seen that the PBR (Presidential Budget Proposal) is a massive set of detailed data representing input from 100s of agencies, but it is still just a request and has no legal authority. So Congress doesn’t have to use any of it, but in reality the PBR is an integral part of the Enactment process.

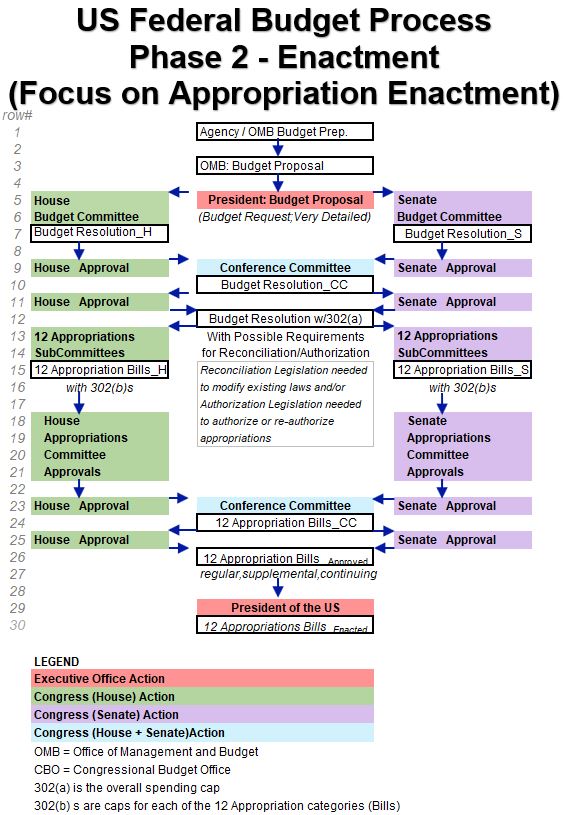

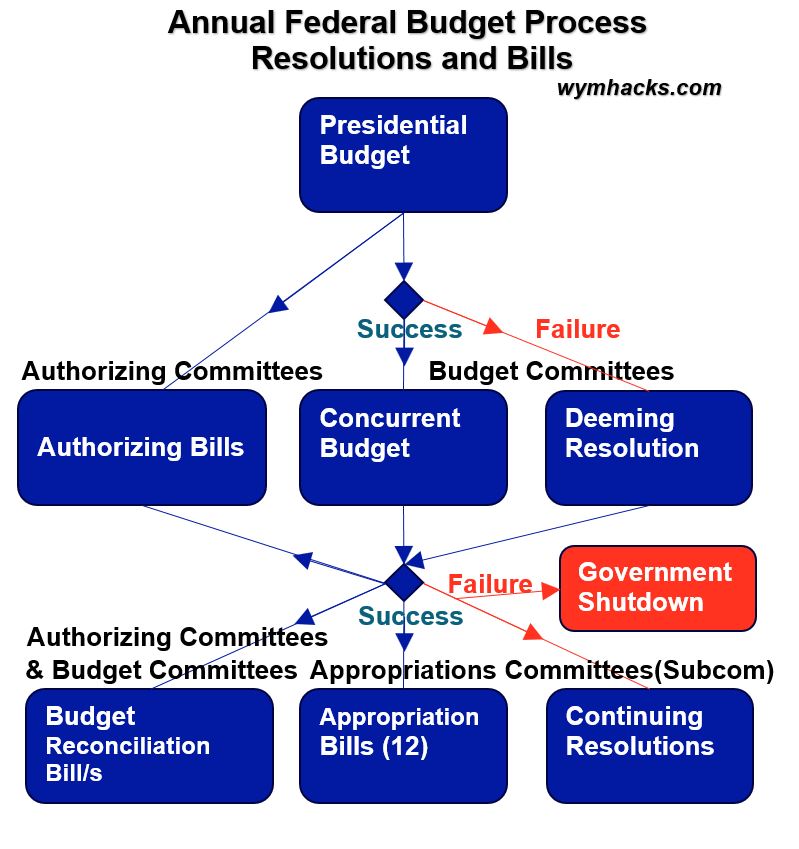

Let’s go through the various steps of the Enactment process as dictated by the Congressional Budget Act of 1974. As you read through the following sections, consider the following:

- Refer to the flow sheet Schematic 12.1 as you read through the steps. Sequential steps are labeled (A) through (I). The color shadings indicate the key group involved i.e. OMB and President (grey), CBO (green), Authorizing Committees (blue), Budget Committees (red), and Appropriations Committees (orange).

- My descriptions and Schematic 12.1 are based mostly on Appendix I and Figure 1 of the GAO document: GAO-05-734SP.

- To see a very crisp and polished description of the Enactment Process, refer to Phil Candreva’s video on the Federal Budget Process (the flowsheet presented in the video is very helpful).

- As you read through the required steps, idiosyncrasies and special rules of the process, ask yourself: (1) How reasonable is it to expect our leaders to complete the process each and every year ? (2) Is the process working as intended? (3) What would you do to improve the process?

Schematic 12.1 – US Federal Budget Process – Phase 2 – Enactment

CBO Submits “Budget and Economic Outlook” Report

Timing: Late January – Early February; Schematic 12.1(A)

The CBO submits budget Baseline Estimates (see green shaded area in Sch.12.1) to the Budget Committees and Appropriation Committees. These estimates are contained in their report titled “The Budget and Economic Outlook“.

According to the CBO, this report presents “… its baseline projections of what the federal budget and the economy would look like in the current year and over the next 10 years if current laws governing taxes and spending generally remained unchanged”.

The report comes out early in the year (Jan-Feb) and is typically updated at least once during the year. You can find much more information at the CBO web site, like this article.

Presidential Budget Request (PBR) is Submitted to Congress

Timing: 1st Monday in February; Schematic 12.1(B)

See the grey shaded area at the top of Sch. 12.1. Congress is supposed to receive the PBR no later than the first Monday in February, but, as we noted in the previous section, the PBR is rarely submitted on time (in recent years for sure).

The PBR is sent out to all the main Enactment Phase players (CBO, Authorization / Appropriations/ Budget Committees).

At the same time, the President transmits Current Services Estimates to Congress. These estimate expenditures for the upcoming fiscal year assuming no changes are made.

Authorizing Committees Work on Authorizing Bills

Timing: These could happen before or after passing of the Concurrent Budget Resolution. ; Schematic 12.1(C)

See the blue shaded areas of Schematic 12.1.

As noted in the “Participants” section of this article, an Authorizing Committee is a standing congressional committee (see Committee definition in Appendix 1 or detailed listing of committees in Appendix 2) that also serves as an Authorizing Committee.

Authorizing Committees have subject matter expertise over certain agency programs and have the role of authorizing these programs; meaning giving people authority and providing the structure and rules under which those programs operate.

Both Mandatory and Discretionary Spending Bills are typically authorized. For example, the House and Senate Armed Services Committees would be Authorizing Committees for certain Department of Defense programs.

The primary goal of the annual Federal Budget Process is to produce 12 Appropriations Bills associated with the upcoming fiscal year’s Discretionary Spending. Each of these Appropriation Bills require an Authorizing Bill or Law.

Recall from the “Controlling Laws…” section that Authorizing Laws create, provide structure, and justify programs (and typically provide guidelines on money that may be spent), while Appropriation Laws typically fund the programs. Remember also that Authorizing Bills for Mandatory Spending programs are also required.

So, work on existing Authorizing Laws that need revisions or updates as well as work on new Authorizing Laws might occur early in the Federal Budget Process. I therefore show path (C) as an early-in-the-process activity, although I think these bills can be worked on at any time during the process (and perhaps other parts of the year also).

Authorizing Committees Transmit “Views and Estimates”

Timing: February; Schematic 12.1(D)

Early in the Enactment Phase the Authorizing Committees with jurisdiction over federal programs

- are (possibly) already starting work on Authorizing Bills (path (C)), but their main function in the beginning steps is to

- produce Views and Estimates reports on spending and revenue levels for programs under their jurisdiction.

- The reports are shared with all the players (see the path of (D)), but are mainly intended for the Budget Committees. The Budget Committees use these reports to develop the total revenue and spending estimates that will be part of their Concurrent Budget Resolution.

As if enough information wasn’t flying around, at about the same time, the Joint Economic Committee submits its recommendations concerning fiscal policy to the Budget Committees (not shown in an already too busy Schematic 12.1!)

Remember, I show path (C) as possibly happening early because usually Authorizing Laws are required to give legal authority to Appropriations Laws.

CBO Prepares an Analysis of the President’s Budget Request

Timing: February; Schematic 12.1(E)

In addition to the Baseline Estimate work it has done, the CBO also does an Analysis of the PBR and shares their findings with the Budget and Appropriations Committees.

So, the mental picture you should have at this point is (if the process is followed as intended): there is a lot of data and a lot of analysis going on.

Budget Committees Create and Deliver a Concurrent Budget Resolution

Timing: February – April (Budget Resolution should be adopted by April 15); Schematic 12.1(F)

We are now in the red shaded area of Schematic 12.1. The House and Senate Budget Committees, armed with the PBR and also the other reports and studies given to them, now go through the legislative process with the intention of passing a unified or Concurrent Budget Resolution.

Schematic 12. 1 indicates the “Legislative Process” with just two words, but we know this can be a complex and drawn out multi-step process (see the “Legislative Process” section of this article where we described the process using Schematic 8.1 shown below).

Legislative Process

- In the House and Senate: Hearings are held.

- In the House and Senate: Markups are made to proposed legislation.

- In the House and Senate: Budget Committee votes on it.

- In the House and Senate: Chamber votes on it.

- House and Senate members get together in a Conference Committee to reconcile and vote on the House and Senate Versions.

- In House and Senate: Chamber votes on it.

- The Conference Committee version is then passed to the President for Approval

Any failure to reach consensus results in a recycling and revision process.

Concurrent Budget Resolution

The Concurrent Budget Resolution provides, per GOA 734sp Appendix I , “… for the upcoming fiscal year and for each of at least the next 4 years)… the total level of new budget authority, outlays, revenues, the deficit or surplus, the public debt, and spending by functional category.”

“The Budget Resolution may include Reconciliation Instructions to the extent necessary to meet the revenue or direct spending targets in the budget resolution.” Refer to CRS report R47336 for more information.

There are special Senatorial procedures that pertain to Budget Resolution legislation. Debate time is limited and therefore Filibusters are not allowed. This means that a simple majority (51/100 or Vice Presidential tie breaker) vote passes the resolution.

One of the important deliverables of a Budget Resolution (see path (G1) in the Schematic 12.1) is called a 302(a) allocation, which sets a ceiling or limit on the total amount of Discretionary Spending for the upcoming fiscal year.

Appropriations Committees take the 302(a) limit and then subdivide the total among the 12 Appropriations Bills.

For example, the 302(a) limit for Fiscal Year (FY) 2016 was $1.017 Trillion (remember this is for Discretionary Spending). The House and Senate Appropriations Committees then established 302(b) allocations by dividing the 302(a) allocation into 12 allocations for each of the Appropriation Bills. You’ll see a full example of the FY2022 allocations later in this section.

Another deliverable/s are any Reconciliation Instructions to the Authorizing committees. These instructions typically require Authorizing Committees to begin drafting new or revised legislation for Authorizing Laws that impact Mandatory Spending programs. Notice, that the Budget Committees use the work of the Authorizing Committees to ultimately pass Reconciliation Bills (see paths (G2 and H) in Schematic 12.1).

The Concurrent Budget Resolution is Not a Law

The Budget Resolution does not become a law and does not get signed by the President. But, any budgetary parameters (like the 302(a) limit) are enforceable through Points of Order.

Points of Order are prohibitions against certain legislation (or congressional action) that violate various rules. Because the 302(a) limits are not self-enforceable, a member of Congress must raise a Point of Order to enforce the limits.

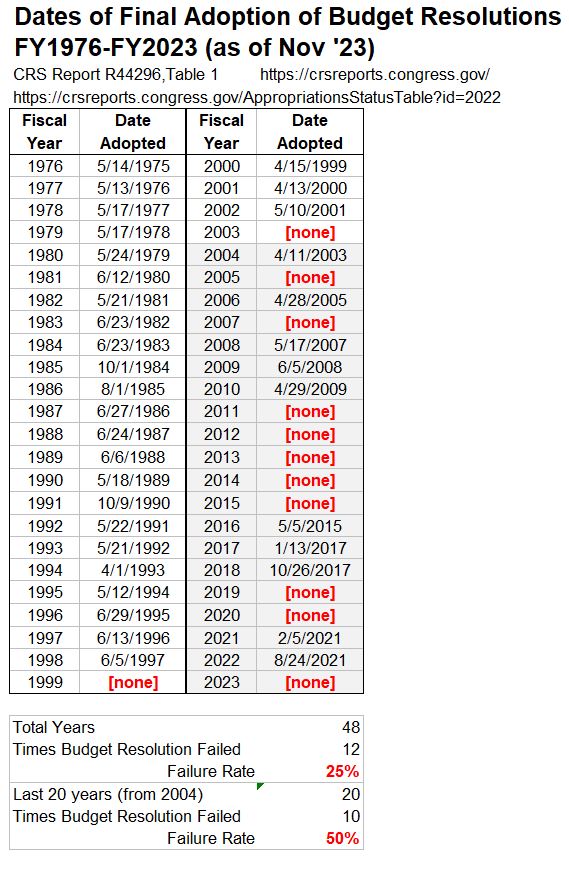

Concurrent Budget Resolutions Don’t Always Pass

How successful has Congress been with passing Concurrent Budget Resolutions? For the last 20 years the answer is, “not real good”. You can look at Appendix 6 for more details on this, so we’ll briefly summarize here.

- In the last 48 years the Concurrent Budget Resolution has failed to pass 12 times (that’s a 25% failure rate).

- In the last 20 years it has failed to pass 10 times (that’s a 50% failure rate) !

In the years in which the Budget Resolution was not passed, the House , Senate, or sometimes both, produce a more streamlined substitute called a Deeming Resolution.

Deeming Resolutions avoid the budget items that contributed to the Resolution not passing and focus on delivering a set of budget allocations to the Appropriations Committees. They are given their name because they are “deemed to serve in place of an annual Budget Resolution”. See the following references for more information on Deeming Resolutions: CRS – R46240 , CRS – R44296 , crfb.org .

Well, that’s depressing. So in the last 20 years, 1 out of every 2 Budget Resolutions have failed to pass (and have been substituted by much simpler and less controversial Deeming Resolutions).

So, what things happen after a Budget or Deeming Resolution is Passed? Two things: (1) Work on Authorizing Laws that are kicked off if the Resolution includes the instructions to do it , and (2) the Appropriations process begins.

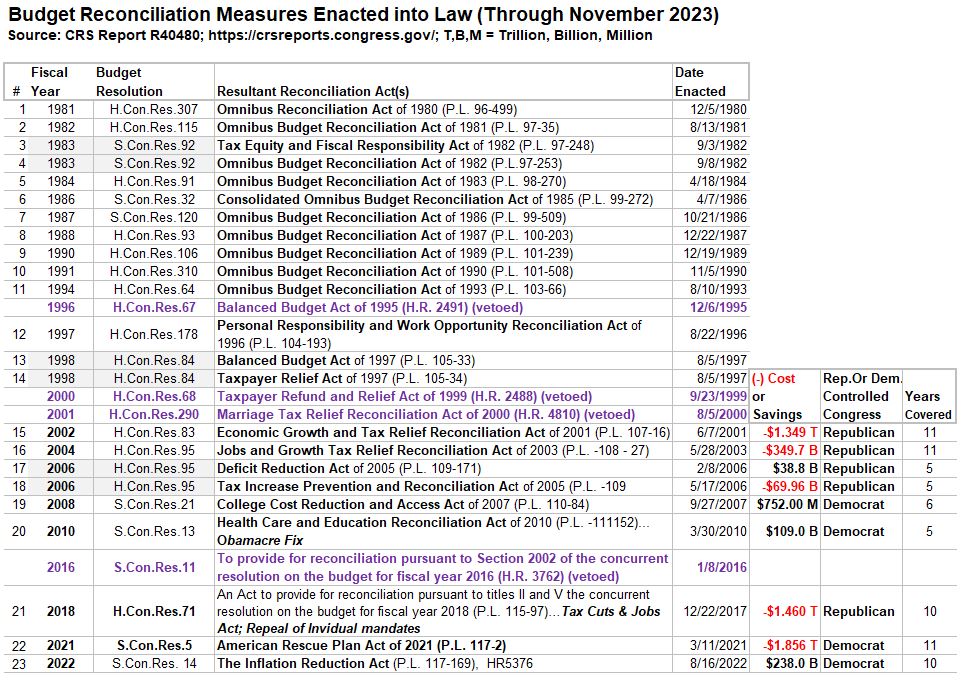

Budget Reconciliation Bills

Timing: May–September; Schematic 12.1(G2) going into the blue shaded section.

Budget Reconciliation Bills are created under expedited Senate procedures (simple majority vote, no filibuster allowed) in order to change existing revenue or direct spending laws.

The process of creating them must begin with Budget Resolution language that instructs the responsible committee/s to create the necessary authorizing legislation. With legislation form the Authorizing Committees, the Budget Committees are responsible for passing Reconciliation Bills (Path (G2) and (H) in Schematic 12.1).

Due to easier voting hurdles in the Senate (No Filibuster allowed and therefore simple majority vote in play), parties have used Reconciliation Bills to pass laws that might (perhaps) not have otherwise been passed.

A total of twenty three (23) Reconciliation Bills have been passed (see Appendix 6 for a complete listing) as of December 11, 2023. Some of them have added massive amounts to our total debt. For example:

- (Republican) Tax cuts in FY 2002 and 2004 (deficit increased by 1.7 Trillion)

- (Republican) Tax cuts (deficit increased by $1.46 Trillion

- (Democrat) Rescue Plan Act (deficit increased by $1.86 Trillion)

Appropriation Bills

Timing: April15 – October 1; Schematic 12.1(G1) going into the orange shaded section.

Once a total Discretionary Spending allocation (302(a)) is provided by a Concurrent Budget Resolution (or Deeming Resolution if Concurrent Budget Resolution has failed to pass, or is late), the Appropriations Committees get to work producing the 12 Appropriations Bills. Check out Appendix 2 for more on congressional committees.

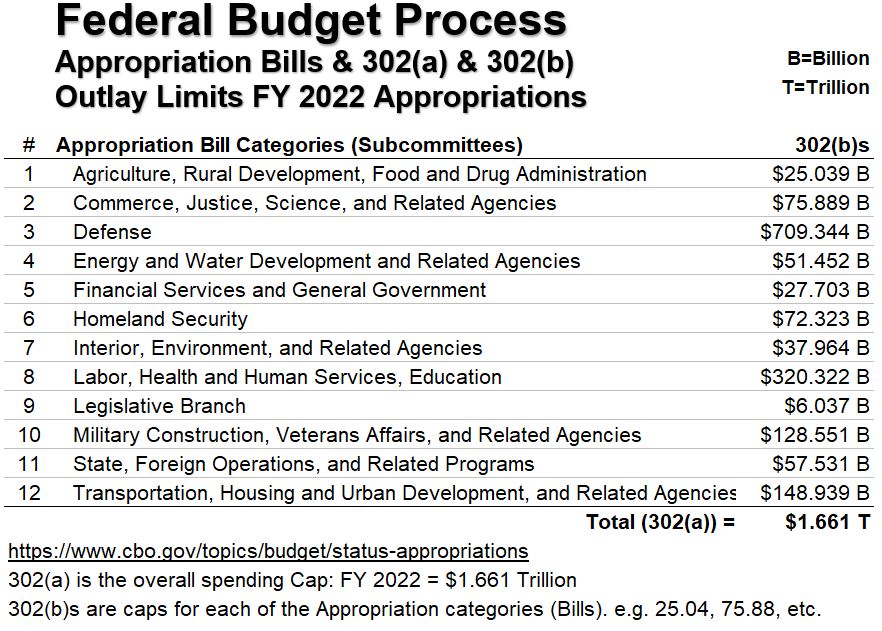

Schematic 12.2 below tabulates the 12 Appropriation Bills for FY2022. Each responsible subcommittee is required to produce a law which provides the budget to all the programs under that particular Bill.

For example, the Homeland Security Appropriations Act or Bill would provide funding to numerous programs/agencies like Customs and Border Protection (CBP), U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), Transportation Security Administration (TSA), Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) etc.

Notice the 302(a) and (b) allocations in Schematic 12.2. For FY 2022, the total limit as dictated by the Deeming Resolution was $1.66 Trillion. Remember, this is Discretionary spending which must be approved on an annual basis.

The 302(b) limits are the numbers listed on each row, for example, the Defense Bill had a whopping $709 Billion USD budget “cap” in Fiscal Year 2022.

Schematic 12.2 – Appropriation Bill Categories with 2022 302(a), 302(b) Allocations

Here are key points describing the Appropriations Process:

- The House and Senate Appropriations Committees and Subcommittees are responsible for producing 12 annual Discretionary Spending bills.

- Each subcommittee (there are 12 in the House and another 12 in the Senate) is responsible for producing legislation for their responsible areas.

- Usually, the House committees start the legislative process for Appropriations Bills.

- The 302(a) total allocation is subdivided into the 12 302(b) sub allocations by the Appropriations Committees. These are then provided to the respective subcommittees.

- Members can invoke Points of Order if any of the limits are violated.

- Points of order are prohibitions against certain legislation (or congressional action) that violate various rules.

- Because the 302 limits are not self-enforceable, a member of Congress must raise a point of order to enforce the limits.

- The CBO also prepares a cost estimate on each appropriations bill and the Budget Committees use this information to check for compliance with budgetary requirements and limits (e.g. the 302 allocations).

- The 12 appropriations Bills can be enacted as 12 separate Bills or combined in different ways. If all are combined, the package is called an Omnibus bill, and if certain numbers are combined they called Minibus bills. How manageable do you think the process gets when these are combined?

- If the Committees fail to enact the 12 Appropriation Bills by October 1, then they must pass a Continuing Resolution. This ensures that Government program funding continues into the next fiscal year.

Appropriations Bill Legislative Process Flow

The Legislative process for developing and approving Appropriations Bills will be the same as described above for the bills and resolutions passed by the Authorizing and Budget Committees.

Schematic 12.3 below is another rendition of the Federal Budget yearly legislative process with a focus on Appropriations Bills. Although the process flow is presented as parallel work flows in the House and Senate, in reality, bills are usually started in one House and at some point are then worked on by the other House.

Regarding Schematic 12.3, we see that :

- To produce an Appropriations Bill you need 2 Budget Committees, 2 Appropriations Committees, and 24 Appropriations Subcommittees. That’s 28 different groups of people and does not even include the Conference Committees.

- Even when Budget Resolutions and Appropriations are agreed to (and it is often that these are not agreed to), the process is complicated and time consuming.

- We are not even considering the additional steps needed to (1) produce Deeming Resolutions when Budget Resolutions fail , (2) to produce Continuing Resolutions when Appropriation Bills fail , and (3) to produce Budget Reconciliations when the Budget Resolution calls for it.

Schematic 12.3 – US Federal Budget Process Flow with a Focus on Appropriation Law Enactment

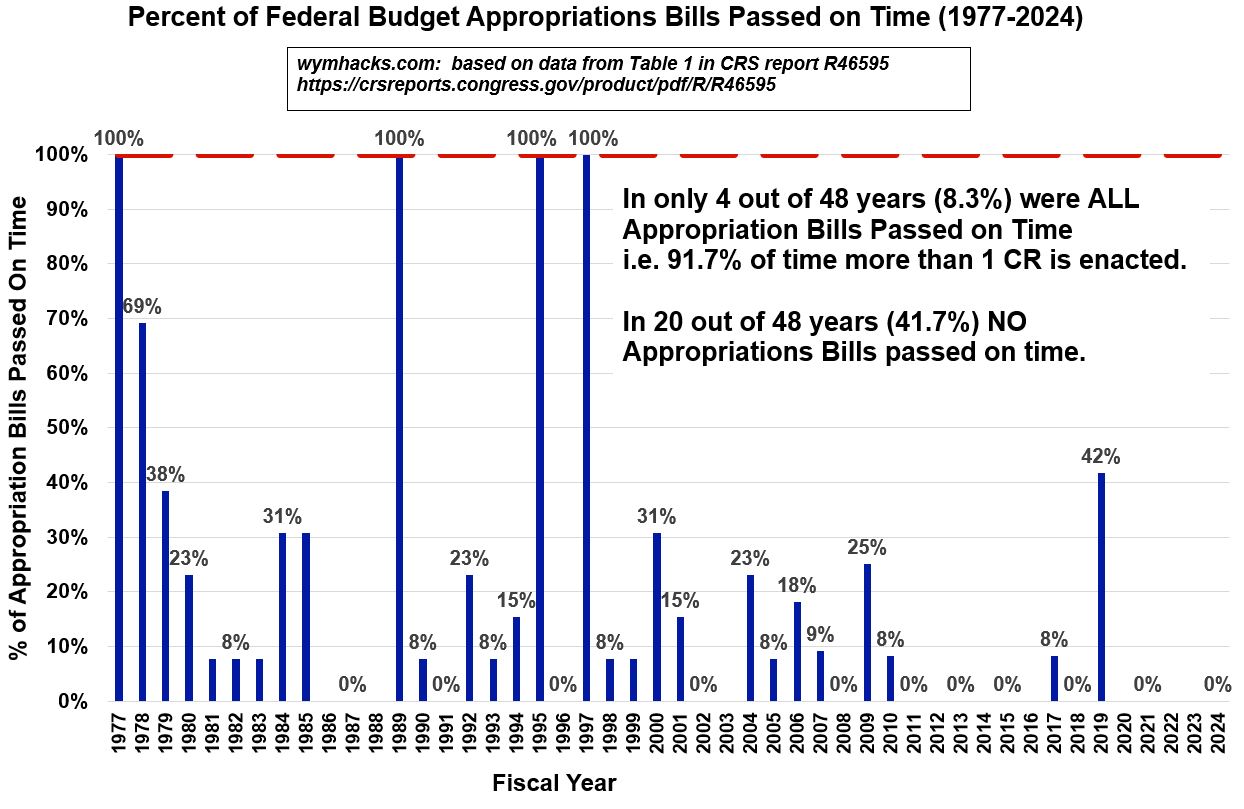

Appropriation Bill Enactment Performance

- All 12 Appropriations Bills were passed on time only 4 times (out of 38; that’s 8.3% of the time).

- In 20 out of 38 years (41.7% of the time), NO Appropriations Bills passed on time.

- Notice all those 0%s in the Chart in recent years.

So , in general , especially recently, Appropriations Bills are not being submitted on time.

Schematic 12.4 – Appropriation Bill Timeliness (FY1977-2024)

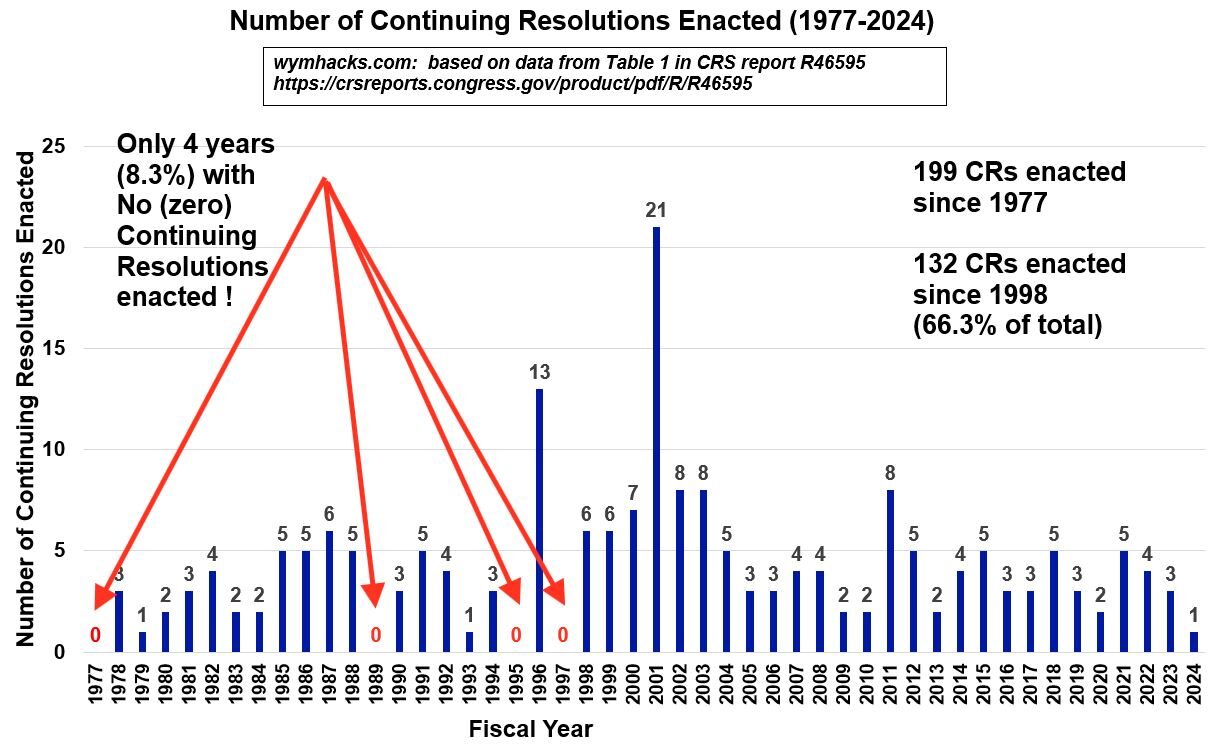

Continuing Resolutions Enactments

Recall that a Continuing Resolution (CR) is a temporary funding measure that Congress uses when Appropriation Bills are not passed or are delayed beyond the start of the Fiscal Year.

Continuing Resolutions operate at the same level of funding as the previous year.

Consider Schematic 12.5 below:

- 199 Continuing Resolutions have been passed since 1977 (48 year period)

- 132 (66.3% of total) have been enacted since 1998 (last 28 years)

- There have only been 4 years where no Continuing Resolutions were passed!

So, since they started doing Continuing Resolutions 48 years ago, there have ONLY BEEN 4 Years where the full set of 12 Appropriations Bills were passed!

Schematic 12.5 – Continuing Resolution Enactments (FY1977 – 2024)

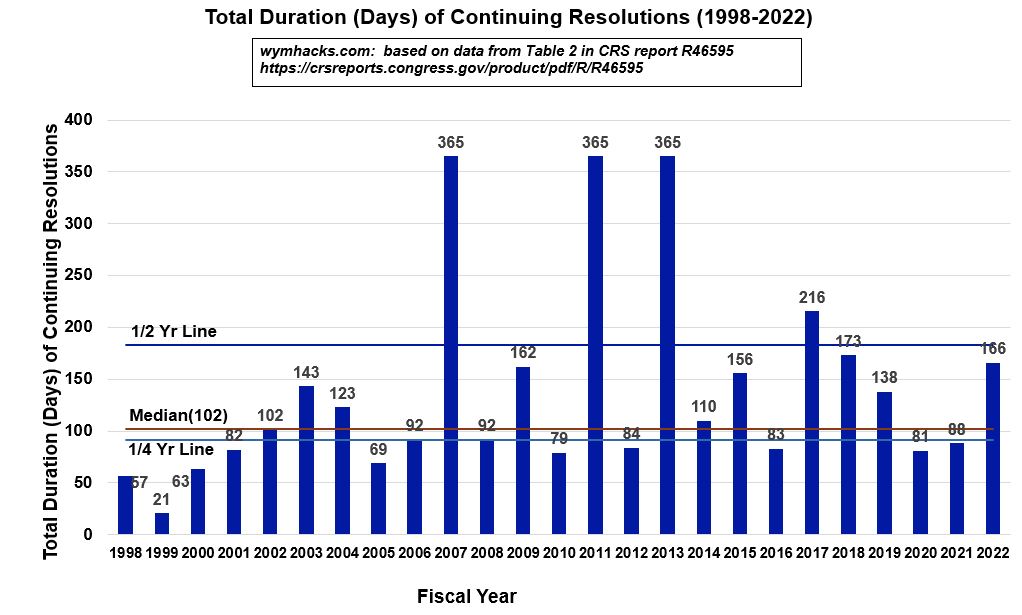

Schematic 12.6 shows the total duration of enacted Continuing Resolutions since 1998:

- The average Continuing Resolution duration was 139 days with a median (middle value) of 102 days.

Schematic 12.6 – Continuing Resolutions Durations (FY1998 – 2022)

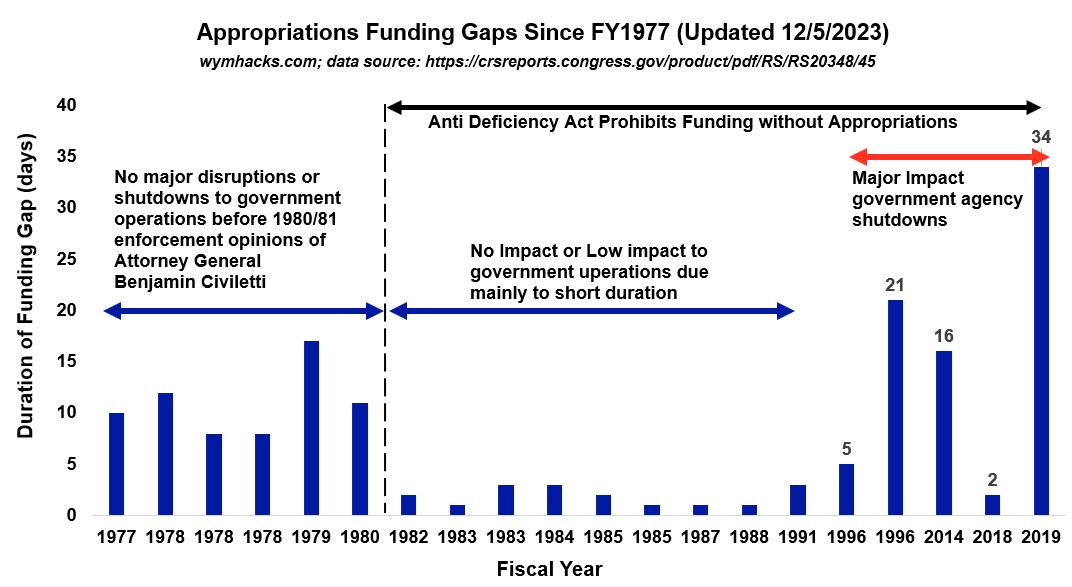

What if Neither Appropriations nor Continuing Resolutions are Enacted?

The Antideficiency Act, with exceptions, prohibits the “obligation of funds in the absence of appropriations.”

If Appropriations (or Continuing Resolutions) are not active by the beginning of the fiscal year (October 1), then the period/s during the fiscal year in which this holds true is/are called Funding Gaps.

A Funding Gap generally requires the shutdown of programs under the Appropriation Bill or Bills that were not funded. Government shutdowns are disruptive and further reduce the efficiency of operations (i.e. people get furloughed and don’t do any work, but they all get paid back for this “non work” in the future).

But, Funding Gaps don’t always (and haven’t always) result in affected Government agency shutdowns: