Menu (linked Index)

Fourier Series and Transforms

Last Update: November 22, 2025

- Introduction

- Fourier Series Trigonometric form

- Fourier Series First Term

- Fourier Series Coefficient for Cosine Terms

- Fourier Series Coefficient for Sine Terms

- Fourier Series – Complex Exponential Form

- Fourier Transform

- Difference between Fourier Series and Transform

- Appendix 1 – Integrals of sin(mt)dt and cos(mt)dt

- Appendix 2 – Integral of sin(t)cos(t)

- Appendix 3 – Integral of Product of Sines

- Appendix 4 – Integral of Product of Cosines

- Appendix 5 – Orthogonality of the Complex Exponential Basis Functions

- Appendix 6 – Fourier Series and Fourier Transform Application Examples

Introduction

The Fourier Series is a foundational mathematical concept that allows engineers to deconstruct and understand complex, periodic signals.

At its core, the series provides a method to represent any periodic function as an infinite sum of simpler, harmonic sinusoidal waves (sines and cosines) .

I first describe the Fourier series in its trigonometric form and I also derive its coefficients (they measure the amplitude of each sine and cosine component present in the signal).

Building on this, the series is converted from its trigonometric form into a more compact and elegant exponential form using Euler’s identity, which simplifies the analysis and derivation of its own complex coefficients.

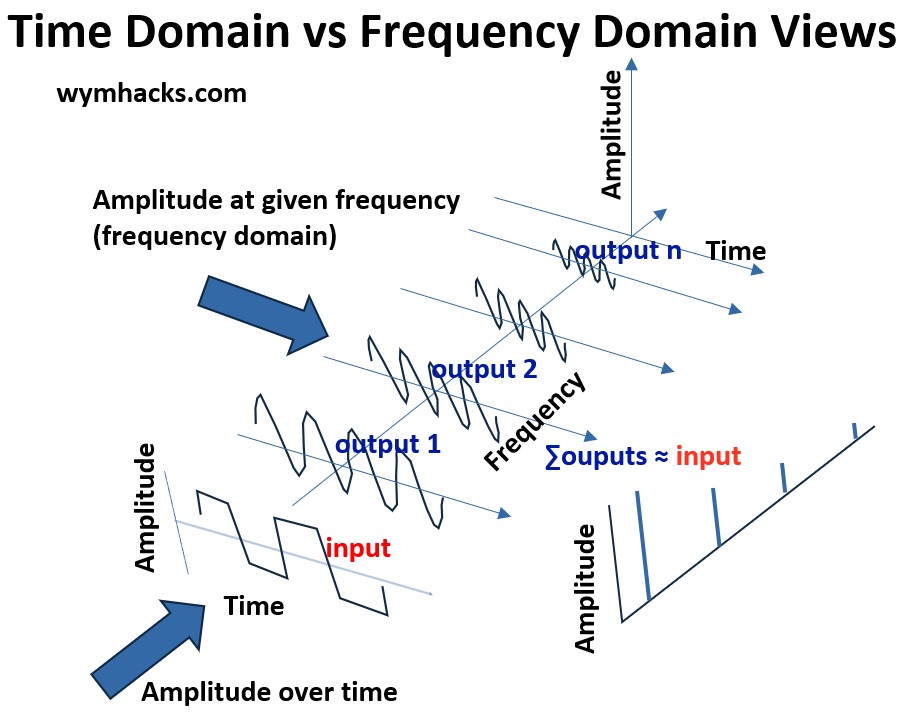

In electrical engineering, the Fourier Series is indispensable; it allows us to transition from analyzing a signal in the time domain (e.g., how voltage changes over time) to the frequency domain (the distribution of power across different frequencies).

This frequency domain perspective is critical for tasks like designing filters to block unwanted noise, analyzing the performance of communication systems, and understanding the behavior of circuits containing non-sinusoidal inputs.

You can check out the great videos below to gain a nice understanding.

I used the first two extensively when I wrote this post.

- Electrical engineering – Unit 6 – Lesson 1: Fourier series – Khan Academy (all 10 of them)

- Complex Fourier Series (Fourier series engineering mathematics) -blackpenredpen

- Electrical Engineering 17: The Fourier Series – Michel van Biezen (see 1 and 7 especially)

- Electrical Engineering 18: The Fourier Transform – Michel van Biezen (see 1 and 9 especially)

Other good links for general understanding

Fourier Series Trigonometric Form

Here are three excellent introductory videos on Fourier series.

- Fourier Series introduction – Sal Khan – Khanacademy

- Electrical Engineering: Ch 18: Fourier Series (1 of 35) What is a Fourier Series? – Michel Van Biezen

- Electrical Engineering: Ch 18: Fourier Series (7 of 35) Summary of How to Find the Fourier Series – Michel Van Biezen

In the early 1800s, Joseph Fourier used the “Fourier” series for the specific purpose of solving the heat equation in his work, Théorie analytique de la chaleur (The Analytical Theory of Heat).

Picture: Jean-Baptiste Joseph Fourier; 21 March 1768 – 16 May 1830; https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joseph_Fourier

His two key contributions were:

- Universality: He boldly claimed that any arbitrary function (even discontinuous, or “piecewise smooth,” functions like the square wave) could be represented by a trigonometric series.

- The Coefficients: He clearly and systematically derived the formulas for the coefficients.

- This gave the series its immense power, providing a concrete way to calculate the weight of every component frequency for any given function.

Two examples of the usefulness of this technique are

- Allows for easier solving of differential equations

- Used in signal processing: The Coefficients are weights on the cosines and sines.

- Tell you how much of different frequencies exist.

Fourier Series: nω0t form

The main idea here is to take a periodic function and represent it as an infinite sum of sines and cosines of different periods or frequencies.

(I) f(t) = a0cos(0ωt) + a1cos(1ω0t) + a2cos(2ω0t) + a3cos(3ω0t) + … + b0cos(0ω0t) + b1cos(1ω0t) + b2cos(2ω0t) + b3cos(3ωt) + …

(II) f(t) = a0 + ∑∞n=1 ancos(nω0t) + ∑∞n=1 bnsin(nω0t)

where

- The terms a0 , an and bn are the Fourier Coefficients.

- They represent the amplitude of each harmonic (sine or cosine) component that makes up the periodic function f(t).

- a0 = The Constant Term = The DC Component or the Zero-Frequency Component.

- an = Fourier Cosine Coefficients

- bn = Fourier Sine Coefficients

- Sometimes summation components are called the AC terms

- t is the independent variable, typically time (but can be a spatial variable also…see third bullet below).

- ω0 is the fundamental angular frequency of the function f(t).

- ω0 = 2πf = 2π/T

- f = frequency in Hz (per sec)

- T = period

- The period (T) of a sinusoid is the horizontal length of one complete cycle of the wave.

- It is the distance along the horizontal axis (usually x or t) after which the function’s values begin to repeat

- technically ω is the angular velocity (rad/s) whose equation

- Note that if t is a “spacial” variable and not a time variable (it might then be labeled s or x or y etc.) ,

- then ω0 would be replaced by a radians/position term (typically called a wavenumber k)

- we’ll assume t is time in this article.

- n is an integer (the harmonic index, n=1, 2, 3,…)

- nω0t is the angular displacement or phase of the n-th harmonic wave.

Fourier Series: T = 2L form

Sometimes, for a general case, T = 2L where it is defined over the range [-L, L]

so, ω0 = 2πf = 2π/T = 2π/2L = π/L and equation (II) becomes

(III) f(t) = a0 + ∑∞n=1 ancos(nπt/L) + ∑∞n=1 bnsin(nπt/L)

Fourier Series: T= 2π form

In electrical engineering, we are often interested in the period T= 2π,

so, ω0 = 2πf = 2π/T = 2π/2π = 1 and equation (II) becomes

(IV) f(t) = a0 + ∑∞n=1 ancos(nt) + ∑∞n=1 bnsin(nt) ; Fourier Series Equation

(V) f(t) = a0 + a1cos(1t)+ a2cos(2t)…+ ancos(nt)+ b1sin(1t)+ b2sin(2t)…+ bnsin(nt)

- where cos(nt) and sine(nt) are basically a shorthand used when

- the function is defined over a period of 2π: T = 2π ; e.g. [-π,π] or [0,2π],

- so t itself is the scaled equivalent of the angular displacement.

We will use versions (IV) and (V) in the derivations in this article.

But What is it? What does it do?

Per Michel Van Biezen: “A Fourier Series is a mathematical way to represent non trigonometric periodic functions as an infinite sum of trigonometric functions.”

The Fourier Series provides a powerful mathematical framework for understanding any periodic function by decomposing it into its simplest, constituent parts.

The core concept is that any periodic signal, no matter how complex its shape, can be perfectly represented as an infinite sum of simple sine and cosine waves.

The input is a single, time-domain periodic function, and the output is a series (a spectrum) of sinusoidal functions.

Specifically, the Fourier Series determines the unique amplitude and frequency for each required sine and cosine term.

When these fundamental components are individually added up, they precisely reconstruct (or closely approximate) the original, complex periodic function.

This representation is often visualized on a chart that displays the amplitude of each calculated sinusoidal component versus its corresponding frequency, showing us the underlying harmonic structure of the signal.

Picture: Fourier Series Output: Discrete values (lines) plotted on Amplitude vs Frequency chart.

See Appendix 6 for examples of where Fourier series (and the Fourier Transform) are used.

Solve for a0 ; Fourier Series 1st Term

Source – First term in a Fourier series – Khanacademy.org

Take ∫2π0 of the Fourier Series equation (V):

(1) ∫2π0 f(t)dt = ∫2π0 a0dt + ∫2π0a1cos(1t)dt + ∫2π0a2cos(2t)dt …+ ∫2π0ancos(nt)dt+ ∫2π0b1sin(1t)dt+ ∫2π0b2sin(2t)dt…+ ∫2π0bnsin(nt)dt

But, (see Appendix 1)

(A1.1) ∫2π0 sin(mt)dt = 0 for any integer m

(A1.2) ∫2π0 cos(mt)dt = 0 for non zero integer m

s0 all the terms go to zero except for the first term.

(2) ∫2π0 f(t)dt = ∫2π0 a0dt = a0t|2π0 = a0(2π – 0) = a02π

(3) ∫2π0 f(t)dt = a02π

(4) a0= 1/2π∫2π0 f(t)dt ; a0 = Average value of “f” over interval between 0 and 2π

Solve for an (n > 0): Fourier Coefficients for Cosine Terms

Source: Fourier coefficients for cosine terms – Khanacademy

Multiply both sides of Fourier Series equation by cos(nt) and take integral ∫2π0 of both sides.

(5) ∫2π0 f(t)cos(nt)dt = ∫2π0 a0cos(nt)dt + ∫2π0a1cos(1t)cos(nt)dt + ∫2π0a2cos(2t)cos(nt)dt …+ ∫2π0ancos(nt)cos(nt)dt+ ∫2π0b1sin(1t)cos(nt)dt+ ∫2π0b2sin(2t)cos(nt)dt…+ ∫2π0bnsin(nt)cos(nt)dt

All except one of the right hand side terms go to zero due to these identities (see appendix 1, appendix 2, and appendix 4):

(A1.2) ∫2π0 cos(mt)dt = 0 for non zero integer m

(A2.1) ∫2π0 sin(mt)cos(nt)dt = 0 for any integers m, n

(A4.1) ∫2π0 cos(mt)cos(nt)dt = 0 when integer m ≠ n or integer m ≠ -n

So, all right hand terms of equation (5) go to 0 except for one term

(6) ∫2π0 f(t)cos(nt)dt = ∫2π0ancos(nt)cos(nt)dt = an∫2π0cos2(nt)dt

But we know that:

(A4.2b) ∫2π0 cos2(mt)dt = π when integer m = n & non-zero

so (6) becomes

(7) ∫2π0 f(t)cos(nt)dt = ∫2π0ancos(nt)cos(nt)dt = anπ

(8) an = (1/π)∫2π0 f(t)cos(nt)dt ; Fourier Coefficients For Sine Terms

Solve for bn : Fourier Coefficients for Sine Terms

Source – Fourier coefficients for sine terms – Khanacademy

Multiply both sides of Fourier Series equation by sin(nt) and take integral ∫2π0 of both sides.

(9) ∫2π0 f(t)sin(nt)dt = ∫2π0 a0sin(nt)dt + ∫2π0a1cos(1t)sin(nt)dt + ∫2π0a2cos(2t)sin(nt)dt …+ ∫2π0ancos(nt)sin(nt)dt+ ∫2π0b1sin(1t)sin(nt)dt+ ∫2π0b2sin(2t)sin(nt)dt…+ ∫2π0bnsin(nt)sin(nt)dt

All except one of the right hand side terms go to zero due to these identities (see appendix 1, appendix 2, and appendix 3):

(A1.1) ∫2π0 sin(mt)dt = 0 for any integer m

(A2.1) ∫2π0 sin(mt)cos(nt)dt = 0 for any integers m, n

(A3.1) ∫2π0 sin(mt)sin(nt)dt = 0 when integer m ≠ n or integer m ≠ -n

Equation (9) reduces to

(10) ∫2π0 f(t)sin(nt)dt = ∫2π0bnsin(nt)sin(nt)dt = ∫2π0bnsin2(nt)dt

We also know that

(A3.2b) ∫2π0 sin2(mt)dt = π when integer m = n & non-zero

so (10) becomes:

(11) ∫2π0 f(t)sin(nt)dt = bnπ

(12) bn = (1/π)∫2π0 f(t)sin(nt)dt ; Fourier Coefficients For Sine Terms

Fourier Series – Complex Exponential Form

source: Complex Fourier Series (fourier series engineering mathematics- blackpenredpen

(IV) f(t) = a0 + ∑∞n=1 ancos(nt) + ∑∞n=1 bnsin(nt) ; Fourier Series Equation

(V) f(t) = a0 + a1cos(1t)+ a2cos(2t)…+ ancos(nt)+ b1sin(1t)+ b2sin(2t)…+ bnsin(nt) ; Fourier Series Equation

We are going to use Euler’s equation to derive the complex exponential form of the Fourier series from the trig form above.

Equations (13) and (14) are the two versions of Euler’s formula and Equations (15) and (16) are cos and sin equalities that are derived from them.

See my blog Circuit Analysis Math Basics: Trig, Complex Numbers, and Euler’s Equation for

- info on Euler’s Equation (Formula) and

- how to compute the sin and cos expression.

(13) ejθ = cosθ + jsinθ; Euler’s Formula

(14) e-jθ = cosθ – jsinθ; Euler’s Formula

(15) cosθ = 1/2 (ejθ + e-jθ) ; cosine definition in terms of exponentials

(16) sinθ = (1/2)(1/j)(ejθ – e-jθ) ; sine definition in terms of exponentials

Express (16) as

(17) sinθ = (1/2)(1/j)(ejθ – e-jθ)(j/j) = (1/2)(1/jj)(ejθ – e-jθ)(j)

but jj = -1 (See this post for more on imaginary number powers), so

(18) sinθ = (1/2)(ejθ – e-jθ)(-j)

Let θ = nt and substitute (15) and (18) into equation (IV)

(19) f(t) = a0 + ∑∞1 an1/2 (ejnt + e-jnt) + ∑∞1 bn(1/2)(-jejnt + je-jnt)

Collect similar terms

(20) f(t) = a0 + ∑∞1 1/2(an – jbn)ejnt + ∑∞1 1/2(an + jbn)e-jnt

We want to get the exponentials in the terms above to be the same.

To do this , we can re-write the 2nd term in (20) if we assume n = -n

∑∞1 1/2(an + jbn)e-jnt = ∑-1-∞ 1/2(a-n + jb-n)ejnt

so (20) becomes

(21) f(t) = a0 + ∑∞1 1/2(an – jbn)ejnt + ∑-1-∞ 1/2(a-n + jb-n)ejnt

(22) Let Cn = 1/2(an – jbn)

(23) and C0 = a0

(24) and Cn = 1/2(a-n + jb-n)

(25) f(t) =∑+∞-∞ Cnejnt ; Fourier Series; Complex Form

Multiply both sides by e-jmt

(26) f(t)e-jmt =∑+∞-∞ Cnejnte-jmt

Take integral ∫2π0 of both sides.

(27) ∫2π0f(t)e-jmt dt =∑+∞-∞ Cn∫2π0ejnte-jmtdt

Right hand side of (27) can have two values

(28) ∑+∞-∞ Cn∫2π0ejnte-jmtdt = 0 if n ≠m

- See Appendix 5 for proof of above

(29) ∑+∞-∞ Cn∫2π0ejnte-jmtdt = 2π if n = m

- because ejnte-jmt = ejnte-jnt = 1

- and ∫2π0 1dt = (t)|2π0 = (2π – 0) = 2π

Assuming n = m, equation (27) becomes

(30) ∫2π0f(t)e-jmt dt = 2πCm

Solving for C, we get (for n = m):

(31) Cn = 1/(2π)∫2π0f(t)e-jnt dt ; Fourier Series Coefficient; Complex Form

Fourier Transform

Watch these great videos:

- Electrical Engineering: Ch 19: Fourier Transform (1 of 45) What is a Fourier Transform? – Van Biezen

- Electrical Engineering: Ch 19: Fourier Transform (9 of 45) Conv. from Fourier Series to Transform – Van Biezen

Recall the Fourier Series equations

(25) f(t) =∑+∞n= -∞ Cnejnt ; Fourier Series; Complex Form

(31) Cn = 1/(2π)∫2π0f(t)e-jnt dt ; Fourier Series Coefficient; Complex Form

The transition from the Fourier Series to the Fourier Transform is a critical step in generalizing frequency analysis from periodic functions to non-periodic functions.

It is achieved by allowing the period of the function to approach infinity.

Generalizing the Fourier Series to Period

The starting equations are for a period T = 2π.

- This means the fundamental angular frequency (its really a velocity not a frequency) is ω0 = 2πf = 2π/T = 2π/2π = 1.

- So, the frequency components are nω0 = n1 = n.

To begin the derivation, we first generalize to an arbitrary period T (where we will later let T → ∞).

Let’s use the variable t for time (i.e. let’s let x = t),and T for the period.

- Period: T

- Fundamental Angular Frequency (velocity really): ω0 = 2π/T = 2πf

- f = frequency

- Integration Interval: Use [-T/2, T/2], which is equivalent to [0, T] since the function is periodic, but the symmetric interval makes the T → ∞ limit clearer.

Re-write equation (25) and (31) as

(32) fT(t) =∑+∞n= -∞ Cnejnω0t

(33) Cn = 1/T∫+T/2-T/2 fT(t)e–jnω0tdt

Rewrite the Coefficient and Isolate CnT

From (33) , let’s move the scaling factor 1/T to the left side and define the integral portion as FT(nω0).

- This FT(nω0) is the precursor to the Fourier Transform.

(34) Cn T = ∫+T/2-T/2fT(t)e–jnω0tdt = FT(nω0)

or

(35) Cn T = FT(nω0)

Rewrite the Series using ω0 and FT(nω0)

Recall that ω0 = 2π/T, so

(36) 1/T = ω0/2π.

Multiply the Right Hand Side of (32) by T/T

(37) fT(t) =∑+∞n= -∞ (CnT)(1/T)ejnω0t

Substitute (35) and (36) into (37)

(38) fT(t) =∑+∞n= -∞ FT(nω0)(ω0/2π)ejnω0t

Move 1/(2π) out of the summation in (38).

(39) fT(t) = 1/(2π)∑+∞n= -∞ FT(nω0)ejnω0t(ω0)

Take the Limit T → ∞

We now take the limit as the period T approaches infinity.

This forces the function to be non-periodic, fT(t) → f(t), and converts the discrete frequency spectrum into a continuous one.

- Function; fT(t) → f(t) ; Periodic function becomes a non-periodic function

- Frequency spacing; ω0 = 2π/T → dω ; As T → ∞ , the fundamental frequency approaches an infinitesimal difference, dω.

- Discrete Frequency; nω0 → ω ; The discrete harmonic nω0 becomes the continuous frequency variable ω.

- Summation: ∑(…)ω0 → ∫(…)ω ; The Riemann sum (a sum of areas: height x width) becomes the integral.

- Integration Limits: ∫+T/2-T/2 (…)dt → ∫∞-∞ (…)dt

The Analysis Equation (Forward Transform)

Applying the limits to the definition of FT(nω0) in equation (34)

(40) limT→ ∞ FT(nω0) = limT→ ∞ ∫+T/2-T/2fT(t)e–jnω0tdt

This defines the Forward Fourier Transform, F(ω):

(41) F(ω) =∫+∞-∞f(t)e–jωtdt

The Synthesis Equation (Inverse Transform)

Applying the limits to equation (39):

(42) limT→ ∞ fT(t) = limT→ ∞ 1/(2π)∑+∞n= -∞ FT(nω0)ejnω0t(ω0)

(43) f(t) = 1/(2π)∫+∞-∞ F(ω)ejωtdω

where,

- f(t): The time-domain function (or signal/spatial function). It is the non-periodic signal whose frequency content is being analyzed.

- t: The time (or space) variable.

- F(ω): The Fourier Transform or the continuous spectrum.

- It is a complex-valued function of the continuous frequency ω that gives the amplitude and phase of every exponential frequency component in f(t).

- ω: The angular frequency variable (in radians per unit time/space). It is a continuous variable ranging from -∞ to +∞.

- j: The imaginary unit, where j2 = -1.

e+-jωt : The complex exponential kernel, representing the basis functions (sinusoids) at every frequency omega.

Here are a few more nice video explanations of Fourier Transforms.

- Fourier Math Explained (for Beginners) Ali the Dazzling

- Fourier Transform Explained (for Beginners) Ali the Dazzling

Return to Menu

Difference Between the Fourier Series and the Fourier Transform

Watch these previously referenced videos for a good explanation of the difference between Fourier Series and Transforms:

- Electrical Engineering: Ch 19: Fourier Transform (1 of 45) What is a Fourier Transform? – Van Biezen

- Electrical Engineering: Ch 19: Fourier Transform (9 of 45) Conv. from Fourier Series to Transform – Van Biezen

The Fourier series and Fourier Transform are both mathematical tools used to analyze functions in terms of their frequency components, but they apply to different types of functions.

The Fourier series is used for periodic functions, decomposing them into a sum of sines and cosines with discrete frequencies that are integer multiples of the fundamental frequency.

This means the output is a discrete spectrum of frequencies.

In contrast, the Fourier Transform is used for non-periodic functions, transforming them into a continuous spectrum of frequencies.

It essentially extends the concept of the Fourier series to functions that don’t repeat, allowing us to see all the frequencies present, not just discrete harmonics.

Think of it this way: Fourier series breaks down a repeating song into its individual notes (harmonics), while the Fourier transform analyzes a single sound event into all the continuous pitches that make it up.

The key difference in the plotted output is that the Fourier Series produces a discrete spectrum, which looks like a collection of separate vertical lines or bars on the frequency axis, representing only the individual, specific harmonic frequencies.

In contrast, the Fourier Transform produces a continuous spectrum, which is a smooth, unbroken curve on the frequency axis, indicating that energy is spread across an entire range of frequencies.

Return to Menu

Appendix 1: Definite Integrals of sin(mt)dt and cos(mt)dt

Source: Integral of sin(mt) and cos(mt) – Khanacademy

(A1.1) ∫2π0 sin(mt)dt = 0 for any integer m

(A1.2) ∫2π0 cos(mt)dt = 0 for non zero integer m

(A1.3) d/dt(cos(mt)) = m (-sin(mt)) = -msin(mt)

(A1.4) d/dt(sin(mt)) = mcos(mt)

Proof for (A1.1):

Write (A1.1) with -1/m multiplied on both sides and use (A1.3):

(A.15) -1/m∫2π0 -msin(mt)dt = -1/m(cos(mt))|2π0

= -1/m ( cos(m2π) – cos(0)) = -1/m(1-1) = 0

Proof for (A1.2):

Write (A1.2) with 1/m multiplied on both sides and use (A1.4):

(A.16) 1/m∫2π0 mcos(mt)dt = 1/m(sin(mt))|2π0

= 1/m ( sin(m2π) – sin(0)) = 1/m(0-0) = 0

Appendix 2: Integral of sin(t)cos(t)

Source: Integral of sine times cosine – Khanacademy

(A2.1) ∫2π0 sin(mt)cos(nt)dt = 0 for any integers m, n

∫2π0 1/2[sin((m+n)t) + sin((m-n)t)]dt

rearrange to:

1/2∫2π0 [sin((m+n)t)dt + 1/2∫2π0 [sin((m-n)t)dt

- (m + n) and (m – n) will be integers and

(A1.1) ∫2π0 sin(mt)dt = 0 for any integer m

so

1/2∫2π0 [sin((m+n)t)dt = 0

and

1/2∫2π0 [sin((m-n)t)dt = 0

so

(A2.1) ∫2π0 sin(mt)cos(nt)dt = 0 for any integers m, n

Appendix 3: Integral of Product of Sines

Source: Integral of product of sines – Khanacademy

(A3.1) ∫2π0 sin(mt)sin(nt)dt = 0 when integer m ≠ n or integer m ≠ -n

(A3.2a) ∫2π0 sin(mt)sin(nt)dt = π when integer m = n & non-zero

(A3.2b) ∫2π0 sin2(mt)dt = π when integer m = n & non-zero

Proof for Equation (A3.1)

Re write (A3.1) using product to sum formula (a trig identity)

(A3.3) ∫2π0 1/2[cos((m-n)t) – cos((m+n)t)]dt

(A3.4) 1/2∫2π0 cos((m-n)t)dt – 1/2∫2π0 cos((m+n)t)dt

for m ≠ n and m ≠ -n:

- then (m – n) and (m + n) are non zero integers and

- (A1.2) { ∫2π0 cos(mt)dt = 0 for non zero integer m}

so equation (A3.4) = 0 , which proves (A3.1.)

(A3.1) ∫2π0 sin(mt)sin(nt)dt = 0 when integer m not equal to n or integer m ≠ -n

Proof for Equation (A3.2)

Start with

(A3.4) 1/2∫2π0 cos((m-n)t)dt – 1/2∫2π0 cos((m+n)t)dt

if m = n, then (m+n) is a non integer. Equation (A1.2) can be applied again so 2nd term of (A3.4) becomes

- 1/2∫2π0 cos((m+n)t)dt = 0

For the 1st term in (A3.4), m – n = 0 so, first term becomes

- 1/2∫2π0 1dt = 1/2(t)|2π0 = 1/2(2π – 0) = π

which proves (A3.2).

(A3.2a) ∫2π0 sin(mt)sin(nt)dt = π when integer m = n.

(A3.2b) ∫2π0 sin2(mt)dt = π when integer m = n.

Appendix 4 – Integral of product of cosines

Source: Integral of product of cosines – Khanacademy

(A4.1) ∫2π0 cos(mt)cos(nt)dt = 0 when integer m ≠ n or integer m ≠ -n

(A4.2a) ∫2π0 cos(mt)cos(nt)dt = π when integer m = n & non-zero

(A4.2b) ∫2π0 cos2(mt)dt = π when integer m = n & non-zero

Proof for Equation (A4.1)

Re write (A4.1) using product to sum formula (a trig identity)

(A4.3) ∫2π0 1/2[cos((m-n)t) + cos((m+n)t)]dt

(A4.4) 1/2∫2π0 cos((m-n)t)dt + 1/2∫2π0 cos((m+n)t)dt

for m ≠ n and m ≠ -n:

- then (m – n) and (m + n) are non zero integers and

- (A1.2) { ∫2π0 cos(mt)dt = 0 for non zero integer m}

so equation (A4.4) = 0 , which proves (A4.1.)

(A4.1) ∫2π0 cos(mt)cos(nt)dt = 0 when integer m not equal to n or integer m ≠ -n

Proof for Equation (A4.2)

Start with

(A4.4) 1/2∫2π0 cos((m-n)t)dt + 1/2∫2π0 cos((m+n)t)dt

if m = n (and n ≠0), then (m+n) is a non integer.

Equation (A1.2) can be applied again so 2nd term of (A4.4) becomes

1/2∫2π0 cos((m+n)t)dt = 0

For the 1st term in (A4.4), m – n = 0 so, first term becomes

- 1/2∫2π0 1dt = 1/2(t)|2π0 = 1/2(2π – 0) = π

which proves (A4.2).

(A4.2a) ∫2π0 cos(mt)cos(nt)dt = π when integer m = n & non-zero

(A4.2b) ∫2π0 cos2(mt)dt = π when integer m = n & non-zero

Appendix 5 – Proof that ∫2π0ejnte-jmtdt = 0 if n ≠m

Orthogonality of the complex exponential basis functions ejnt and e-jmt over the interval 0 to 2π

This is the proof for equation (28):

(28) ∑+∞-∞ Cn∫2π0ejnte-jmtdt = 0 if n ≠m

Consider the following integral of the product of complex exponentials

(A5.1) ∫2π0ejnte-jmtdt = 0 if n ≠m

Use the rule of exponents to combine the terms in the integral:

(A5.2) ∫2π0ejnte-jmtdt = ∫2π0ej(n-m)tdt

Let k = n-m.

Since n and m are integers, k is also an integer.

Because we are considering the case where n ≠ m, we have k ≠ 0.

(A5.3) ∫2π0ejktdt ; k ≠ 0

(A5.4)∫2π0ejktdt = 1/(jk)ejkt|2π0

(A5.5)∫2π0ejktdt= 1/(jk)(ejk2π – e0)

Recall Euler’s Formula

(A5.6)ejθ = cosθ + jsinθ; Euler’s Formula

(A5.7)ejk2π = cos(2πk) + jsin(2πk)

(A5.8)2πk is an integer multiple of 2π

So for any integer k,

- cos(2πk) = 1 and

- sin(2πk) = 0

(A5.9) ejk2π = cos(2πk) + jsin(2πk) = 1 + j(0) = 1

Substituting this back into equation (A5.5) we get

(A5.10) ∫2π0ejktdt= 1/(jk)(1 – e0) = 1/(jk)(1 – 1) = 0

This proves that

(A5.1) ∫2π0ejnte-jmtdt = 0 if n ≠m

The fact that this integral is zero is known as the orthogonality of the complex exponential basis functions ejnt and e-jmt over the interval 0 to 2π.

Appendix 6 – Fourier Series and Transform Application Examples

Here are five examples of where Fourier series (and its close relative, the Fourier Transform) are used:

Audio and Signal Processing (MP3/JPEG Compression)

- The Problem: A raw audio or image file contains a huge amount of data in the time/spatial domain.

- To store and transmit it efficiently, the data must be compressed.

- The Fourier Solution: The complex signal (sound wave or image pattern) is decomposed and then out of hearing range frequencies discarded

- the file size is drastically reduced while maintaining near-original quality.

Electrical Engineering (Circuit Analysis)

- Fourier series are fundamental to analyzing circuits driven by non-sinusoidal periodic power sources.

- The Problem: When an electrical circuit is excited by a periodic signal that isn’t a simple sine wave (like a square wave or a sawtooth wave), calculating the circuit’s response (currents and voltages) is very difficult in the time domain.

- The Fourier Solution: The complex periodic input voltage or current is decomposed into its constituent AC harmonic components using a Fourier series.

- The Application: Since the circuit’s components (resistors, inductors, capacitors) behave linearly for each individual sine wave (harmonic), engineers can calculate the response to each harmonic separately.

- The total circuit response is then the simple sum (superposition) of all the individual harmonic responses.

- This is vital for analyzing power quality and designing harmonic filters.

Music and Acoustics (Harmonic Analysis)

- Fourier analysis provides a quantitative way to understand the quality of sound.

- The Problem: Two instruments playing the same note (e.g., Middle C at 261.6 Hz) sound different because of their timbre.

- The Fourier Solution: The sound wave produced by each instrument is analyzed. The lowest frequency component is the fundamental frequency (the pitch, f).

- The other, stronger components are the overtones or harmonics (2f, 3f, 4f, etc.).

- The Fourier coefficients determine the amplitude and phase of each of these harmonics.

- The Application: The unique distribution and intensity of these harmonic coefficients are what define the instrument’s timbre.

- Engineers use this analysis to design acoustic systems, musical synthesizers, and equalization (EQ) filters that manipulate specific frequency bands.

Solving Partial Differential Equations (The Heat Equation)

- The initial purpose of the Fourier series was to solve problems in physics, particularly heat conduction.

- The Problem: How does heat flow and dissipate over time in an object (e.g., a metal rod or plate) that starts with a non-uniform, arbitrary temperature distribution?

- This is governed by the Heat Equation (a Partial Differential Equation).

- The Fourier Solution: The arbitrary initial temperature distribution T(x, 0) ,which is a function of position x, is represented as a Fourier series.

- The natural solutions to the Heat Equation are simple exponential decay functions multiplied by sine/cosine waves (the spatial harmonics).

- The Application: By matching the Fourier series of the initial condition to the natural solutions, the coefficients for the complete solution are found.

- This technique (called separation of variables) is the classical way to find the time-dependent temperature profile T(x, t) throughout the object.

Vibration and Structural Analysis (Resonance)

- In mechanical and civil engineering, understanding vibrations is crucial for safety.

- The Problem: Engineers need to identify the natural frequencies of a mechanical system (like a bridge, a building, or a spinning motor) to ensure that external forces (wind, earthquakes, motor imbalance) won’t cause resonance, which can lead to catastrophic failure.

- The Fourier Solution: Sensors measure the raw vibration signal (acceleration over time).

- The Fast Fourier Transform (FFT)—a highly efficient algorithm for calculating the Fourier series coefficients—is used to convert the raw signal into a frequency spectrum.

- The Application: The spectrum immediately reveals which frequencies are present and their respective energy levels.

- Peaks in the spectrum clearly identify the system’s dominant natural frequencies and help diagnose problems like bearing defects or shaft misalignment in rotating machinery.

Disclaimer: The content of this article is intended for general informational and recreational purposes only and is not a substitute for professional “advice”. We are not responsible for your decisions and actions. Refer to our Disclaimer Page.